The Exhibition Design by SITE

“I don’t design clothes for the queen; but for the people who wave to her when she walks by, ”said fashion designer Willi Smith, who drew many of his best ideas from street life in New York City. His label, WilliWear, was the first streetwear brand, and his clothes, released in the late 1970s, were modern, comfortable, and expressive – think oversized blazers and pants that all body types can wear, chunky knits and fabrics sourced from all over the world. (One of his most popular pieces was a one size fits all cargo pants with adjustable waistband.) Smith often sold models of his designs, so people could make his clothes at home. So, in the early 1980s, when he wanted to open his own showroom, he told James Wines, founder of the architecture and environmental art studio. TO PLACE, to make it “as far away from Ralph Lauren as possible”. Smith took Wines to his favorite haunts on the west side – Christopher St. Pier and nightclubs close – and as they walked around the area, he pointed out all of the materials and textures he loved. Wines thought: Let’s make the street.

Under cover of night, Wines drove his Ford Explorer through the same areas Smith took him – which was being redeveloped and highway removal at a breakneck pace – and picked up all the trash he had. could find: rolls of chain link fencing, bricks, metal siding, shipping pallets and even stack cleats. The entirety of Smith’s office – which featured a huge desk that looked like two unfinished brick walls topped with glass – came from a single construction site. Every once in a while, they hit the jackpot: an overturned fire hydrant or a broken lamppost. “We were very careful not to affect public safety, but it was really like a game,” says Wines, whose job it is to abandon architectural conventions. “I like this idea of the unwanted world, because you can do something with it.”

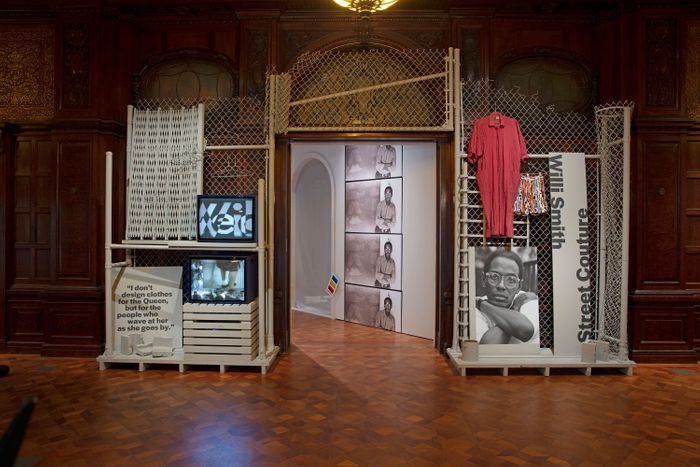

Willi Smith (left) designed what he called “democratic” fashion. The streetscape-inspired showroom was a backdrop for the type of clothing he made (right). From left to right : Photo: Courtesy of Kim SteelePhoto: Peter Gould / Courtesy of Fashion Institute of Technology

Willi Smith (left) designed what he called “democratic” fashion. The streetscape-inspired showroom was a backdrop for the type of clothing he …

Willi Smith (left) designed what he called “democratic” fashion. The streetscape-inspired showroom was a backdrop for the type of clothing he made (right). From above: Photo: Courtesy of Kim SteelePhoto: Peter Gould / Courtesy of Fashion Institute of Technology

Set foot inside Smith Women’s Showroom, which opened on West 38th Street in 1982, was like walking down an industrial downtown street, painted entirely in dark gray. The “Ghost cityscape”Was as much an artistic experience as a place to shop for clothes, as Smith intended, and paved the way for concept shops like Dover Street Market and Opening Ceremony. The stores belonged to the same universe for which the clothes were designed. He hung clothes directly on the chain link fences and posed mannequins sitting on concrete blocks, just like a person would on the street. When Smith held fashion shows in showrooms, models climbed fences, hung on pipes, and sat on fire hydrants. “It was an absolute genius to have designed, for the first major boutique of African-American fashion designers, an environmental framework that not only spoke to the designer’s creative vision for clothing, but also defined the man, the woman. politics and the social conditions of the time ”, the architect Jack Travis, writing. “The results were undeniable.

So when Cooper Hewitt mounted a retrospective of Smith’s daring career in “Willi Smith: street sewing”, Which is open until October 24, there was no question of who would design the exhibition. It had to be SITE. Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, curator of the exhibition, said: “The SITE and WilliWear collaboration so perfectly represents two complementary value systems that collide to challenge the status quo, both transforming basic materials – a shovel, a skirt , a brick, a blazer – in an act of rebellion, a moment of becoming built by style and intelligence.

Photo: Matt Flynn / Smithsonian Institution

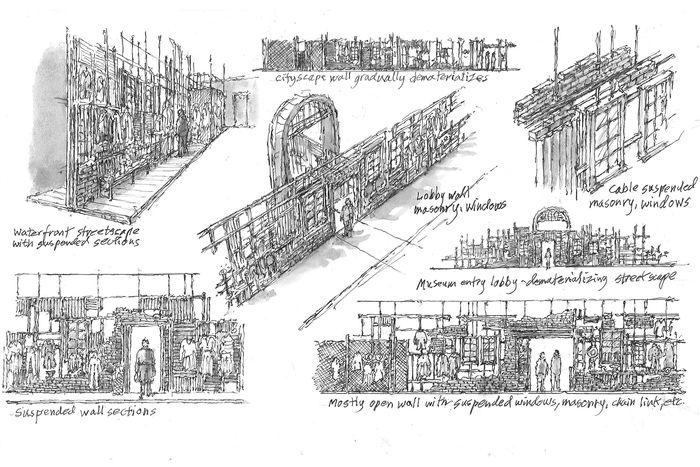

An exhibit on Willi Smith had to include his showroom in one way or another. But representing architecture in a gallery setting is always a challenge, as the experience of architecture requires a body in space. The photos, videos or models of a Smith showroom can go no further. So Wines, now 89, worked with Chermayeff Studio, production studio Supermatic, and his daughter Suzan’s wines, to recreate the most iconic elements of Smith’s showrooms and office – the collage of street artifacts, the masonry desk – in the gallery.

But for Wines, there was also an inherent tension in replicating this concept in the museum. “The whole environmental art movement in Soho in the ’70s and’ 80s, which I was a part of, was based on leaving galleries,” says Wines. “Our whole philosophy moved away from all these projectors, brackets, plinths and frames. We are all either in the landscape or in the street. (Some of SITE’s most famous works have been to transform big box retail stores into works of art which made the buildings appear to be collapsing or peeling off.) Plus, Cooper Hewitt is a Georgian mansion that once belonged to Andrew Carnegie. An iconic Upper East Side building is about as far removed as possible from Wines’ philosophy, which rejects architectural formalism, and the aesthetic of downtown Smith. Smith’s showrooms and office were set in vast raw industrial spaces with cement floors, exposed beams, and large windows. The gallery, meanwhile, has parquet floors, ornate carved moldings, coffered ceilings, and stained glass windows. “The idea of exhibition space is a formalization of space,” says Wines. “It became this big problem of … How am I going to keep this in mind? How am I going to honor the artist?“

Wines’ conceptual sketches for Cooper Hewitt’s exhibition on Willi Smith represented streetscapes in a state of dematerialization.

Illustration: Courtesy of James Wines

Part of the appeal of the original exhibit hall was that the artifacts all existed in the city before they were assembled into a recreation of a downtown street. “In the 80s a lot of the energy was related to the harshness and the reality of the whole thing,” says Wines. “We tore up entire facades of buildings and were lucky enough to find all these buildings ragged. So we had pretty much everything we needed to slip into the showroom and do this freewheeling collage. And Willie loved it, sure, and it was handy because you can hang clothes anywhere.

But SITE couldn’t attach anything to the museum’s wooden walls, or put artifacts directly on the floor, so they designed stand-alone exhibition platforms. In addition, the objects in the exhibition are now all precious. Ephemera like magazine articles, invitations to fashion shows and posters had to be placed in display cases to protect them. Wines was particularly shocked to learn that curators couldn’t always hang clothes directly on the exhibit structure, as Smith would have done in his shop. “How could touching pipes hurt a t-shirt?” »Notes on the wines. (Some of the Smith T-shirts once sold for $ 40 now go for $ 1,400.)

Photo: Matt Flynn / Smithsonian Institution

Photo: Matt Flynn / Smithsonian Institution

Wines also couldn’t surreptitiously source materials like they once did at midnight, as those abandoned buildings and demolished piles of materials no longer exist in the city. But Cat Garcia-Menocal, the construction manager at Supermatic, competed over materials from construction suppliers to get closer to what was in the original showroom. It was brand new, of course, not rough from years of wear and tear on the exterior. When it came time to recreate Smith’s site office, the designers scaled it down and used it to display some of his personal items, like his round plastic glasses.

Until the end, Wines wondered how the scenography of the exhibition would unfold. But when he was finally able to visit the exhibit in person (the museum reopened this summer after having to close for COVID just a week after the exhibit began), he was delighted to find that all of the Georgian adornments were on display. were faded into the background, as he had hoped, and he felt as close to Smith’s world as he could get in 2021. I felt that too. Walking from the wood-lined hallway of the museum and rounding the corner of the exhibit was exhilarating. He did not have the exact sense of reality that Wines described as having the original showrooms, but that’s understandable, and there was a feeling of awe. “It still looked like Willi Smith, he still had that bonding feeling,” Wines says. “We managed to do it, so it at least preserves the memory of the showroom.”

Photo: Matt Flynn / Smithsonian Institution