Can Anything Stop New York City Drivers From Honking?

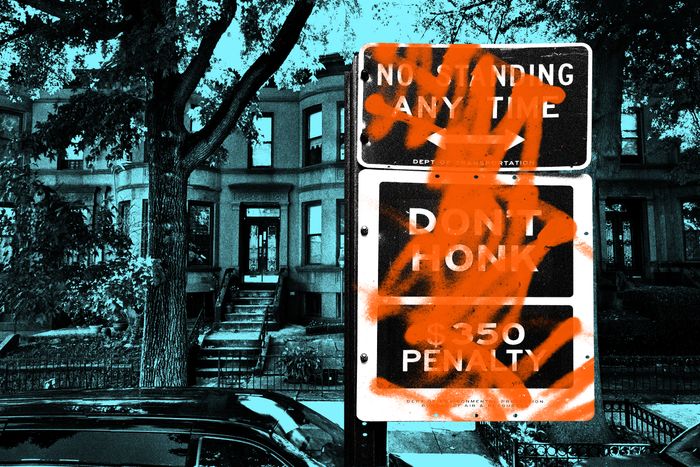

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Getty, Google Earth, Flickr

The honking outside my apartment is incessant. It happens like this: A person driving a truck will get stuck behind a double-parked or idling car on my narrow street, and they will honk. A person stuck behind the truck will also honk, as will the Amazon van stuck behind the person behind the truck. (Sometimes another person gets stuck behind the Amazon van and starts to honk, oblivious to the line forming in front of them.) None of this accomplishes anything. The second layer of noise on my block is the sound of people screaming at drivers from their apartment windows, which at first I did not participate in but now do. Like the honking, screaming at the honking doesn’t accomplish anything, but at least it feels good.

Living in the city means dealing with a certain amount of noise. But must it mean ceding our peace of mind to the honking? I decided to try to fix it.

Things started simply enough: Writing an email to my city councilmember after being woken up one too many times as someone laid into their horn for an entire minute. “Is there any way to stop drivers from honking?” I wrote. They never responded. I pressed on. According to 311, “horn honking is only allowed as a warning of danger,” but good luck enforcing that. The same section of the city’s guide to noise reads that, once called, “Officers from the New York Police Department will respond within eight hours when they are not handling emergencies. They will be able to take action if the noise is still happening when they arrive.” What this amounts to is something like a honking honors system.

The guidance on honking has been similarly loose since, seemingly, the advent of cars in New York City. In 1930, the Noise Abatement Commission waged a campaign for quiet that included “automobile horn tooters,” arguing that “the average horn is a great deal louder than is necessary to serve its purpose.” The police then began issuing warnings to drivers. Five years later, during Mayor Fiorello La Guardia’s own anti-noise campaign, the city found that most of the complaints being submitted by residents were still about honking. His administration responded by banning “prolonged and unreasonable” honking, for a first-time fine of $1. As the city continued to update its noise code over the decades, excessive, nonemergency honking remained banned. And endemic. Mayor Ed Koch escalated things during his tenure by installing “Don’t Honk” signs across the city — reminding drivers that there was a $350 fine for nonemergency honking. (As Koch told the New York Times about honkers: “Those people are the worst.”) This also did not work: In 2013, the Department of Transportation commissioner removed the signs as part of a decluttering campaign due to the fact that the city didn’t have any proof that they reduced honking.

No one would deny that the car horn isn’t a necessary part of the car. The inventor of the Klaxon horn, the literal originator of Awooga!, came up with it after he almost hit a pedestrian. Except what, exactly, rises to the level of a honk is entirely within the driver’s discretion. And the answer in New York, now but perhaps for all of eternity, seems to be: everything. (As Mary Norris once put it, New York City drivers “are practically anarchists.”) In a 2009 road-rage survey conducted during rush hour, New York drivers topped the list for their reliance on the horn. Gothamist once sent someone out to ask drivers why they were honking in gridlock outside of the Holland Tunnel. As one driver put it: “Listen, this is New York. Even if we don’t move, we honking.”

With little hope of civic relief, I turned to the place where one goes to get the answers to life’s most pressing questions: Reddit. One post suggested that it should cost $10 per honk with some kind of tracker in your car that would bill you. Another proposed that car manufacturers should make the honk sound as loud inside the car as a way to equally distribute impact, thus inspiring discretion. Which, surprisingly, someone tried: In 2013, behavioral scientists Anand Damani and Mayur Tekchandaney invented a device called Bleep that would make an annoying beeping noise inside the car every time a driver honked. To stop the beeping, drivers had to press a red button with a frowny face on it. “A little bit of medicine back to the driver,” Damani said in a TED Talk. They tested the device on drivers in Mumbai for six months and when Damani presented the results — no accidents and a 61 percent reduction in honking — the audience cheered.

I reached out to Damani to see if anything ever happened with Bleep. He emailed me back saying that the New York Taxi and Limousine Commission had reached out to him for a pilot but nothing ever came of it. As for the car companies — he said he never approached them in the first place. “I never expected car manufacturers to install Bleep because it wouldn’t help them sell more cars,” he wrote.

A bit despondent, I decided to talk to Arline Bronzaft, an environmental psychologist and five-decade veteran of the city’s effort to reduce noise, which — as proven by my slow turn to insanity and elevated rates of heart disease in louder neighborhoods — is a genuine public-health concern. Bronzaft, unlike my city councilmember, called me back immediately. She was still mad, all these years later, about the removal of the “Don’t Honk” signs. The signs were not the problem, she said, it was the lack of enforcement. The year before the signs came down, the NYPD had issued a measly 206 summonses for honking. “If you have a sign that says don’t honk, then that’s a reminder that depends on the goodwill of people,” Bronzaft said. “But if under that sign it says $350 penalty and you never issue it, then you might as well forget the $350.”

Bronzaft also pointed me toward noise cameras as a potential spot of hope. Similar to speed cameras, noise cameras can automatically ticket drivers whose modified mufflers or honking exceeded 85 decibels. Councilmember Keith Powers (who is not my councilmember, who, again, did not write me back) was also bullish on noise cameras. Powers was the sponsor of a bill that passed last year making noise cameras a city-wide program. He seemed to share my passion on the issue. “We’ve long retreated away from actually trying to solve this problem when we should be leaning in,” he said. All of this is nice in theory, except, like most of the city’s enforcement strategies, critics have flagged privacy issues and the potential that the placement of these cameras could disproportionately target poor communities of color.

The cameras also have their technical limits — Hell Gate obtained results of a 2022 DEP pilot in which 38 percent of captured noise events had footage that was too blurry to use. Another 21 percent had cars with missing or obscured plates — something that drivers intentionally do to confuse speed cameras.

Which returned me to my original state of hopelessness. (Cars honked while I wrote this.) Who was I to think I could silence the horns? Who were any of us, a long line of suckers through the last century? But Bronzaft assured me that change was possible. Maybe, starting with me, starting today, a quieter city could be born. “You could really provoke thought on this issue,” she said. It was nice to hear. But someone probably told La Guardia the same thing.