The Lower East Side’s (Not Very Well Known) Black History

Since its founding in 1988, walking tours of the Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side have told the story of the European, Chinese and Puerto Rican families who made the area their home during the 19th and 20th centuries. But they never included the history of black New Yorkers in the area. The founders of the museum had wanted to incorporate African American stories when planning its first exhibits in the 1980s. “As they researched these buildings, they thought they were going to find stories of black New Yorkers who lived there. in these buildings, and they didn’t, ”said Kathryn Lloyd, the museum’s director of programs. “But of course, that’s not a sufficient answer.” The Tenement Museum is starting to fill this gap with a new walking tour titled “Recover black spacesWhich focuses on the history of people of African descent in the neighborhood, dating back to when Manhattan was a Dutch colony in the 17th century. The five-stop tour, which officially kicks off on June 12, is part of a larger initiative to highlight black history the museum has overlooked, which also includes an upcoming exhibit on the Moores, a family black who moved into a LES building in 1869.

Here are some highlights of the visit.

A section of Allen Street that was once part of Sebastiaen de Britto’s farm.

Photo: courtesy of the Tenement Museum

Highlight: The farm was part of the first free black community in North America.

What is the story?: The land here once belonged to Sebastiaen de Britto, a once enslaved African who was brought to the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam from Santo Domingo in the early 17th century. De Britto and his wife, Isabel Kisana, were among a group of 30 enslaved people who petitioned the Dutch West India Company for their freedom and received land. After obtaining the so-called “half-freedom” (they still had to work for the Dutch West India Company whenever they were summoned, and their children were still considered the property of the company) in 1647, De Britto and at least two other freed black families built houses and began to cultivate the land which is now the LES. Britto’s six-acre farm was roughly between what is now Ludlow and Bowery, east to west, and Rivington to Broome, north and south. The farm was part of a much larger community of free black farms that ran along a strip in the middle of the island from Canal Street to Midtown, acting as a barrier, as Lloyd put it, between the Dutch and the colonies of Lenape further north.

What’s left: There is nothing left of Britto’s farm. The land grant expired in 1650, and there is no mention of Britto or Kisana in historical records after that. When the British took control of New Amsterdam in 1664, they stripped black rights, including the right to own land.

What is there now: The famous Sutton House, the home of cotton merchant George Sutton in the 19th century. As Lloyd said, “This land, over the centuries, has grown from a stage, in some ways, of freedom and advocacy for black New Yorkers to… a site of the history of slavery and of New York’s dependence on enslaved people to build us the wealth that this city possesses today.

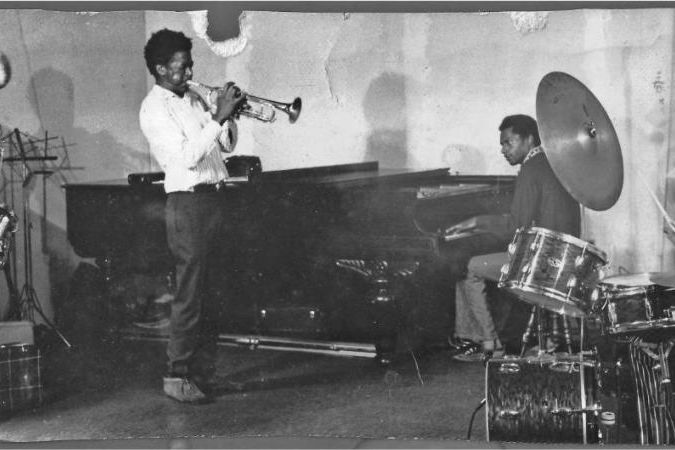

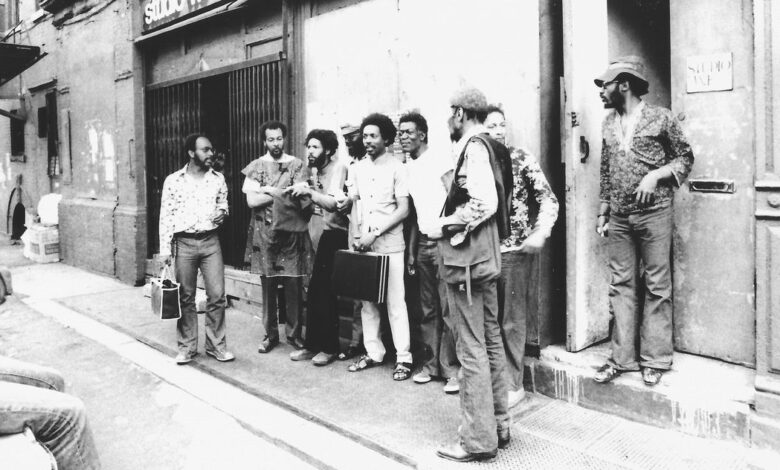

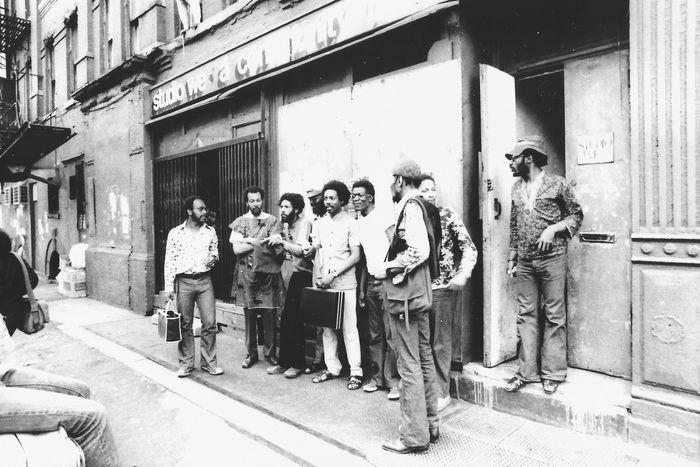

A studio that we rehearse.

Photo: Courtesy of the Tenement Museum, Michael Heller, “Loft Jazz: Improvising New York in the 1970s”

The condominium apartment building now located at 193 Eldridge Street.

Photo: Valeria Ricciulli

Highlight: Studio We, a community music performance and rehearsal space built inside an abandoned building in 1968.

What is the story? In the late 1960s, the five-story building at 193 Eldridge Street was, like many buildings in the city at the time, nearly collapsing. It had a collapsed roof, no plumbing, and many floors had collapsed. In 1968, the building keeper, Howard Green, was on his way to Europe and his friend, jazz trumpeter James Dubois, asked him if he could take care of it. He and several other musician friends moved into the building and turned it into a jazz venue they called Studio We. They built a stage on the sixth floor and set up other performance and practice spaces throughout the building. Studio We quickly became in the heart of the city Loft Jazz Stage – an avant-garde form drawn from both jazz traditions and pop genres, and has been performed almost exclusively in residential settings such as older apartment buildings. Dubois’s brother opened a soul-food restaurant on the first floor, where people could grab food for shows. The space symbolized the idea of the late 1960s “that black Americans should be responsible for creating the world and the society they want to see for themselves,” Lloyd says. “Ideas of independence from the white cultural structures and white financial structures that dominated the city, society, and jazz music at the time.”

What’s left: Aside from the dark red columns flanking the entrance to the building, nothing remains of Studio We. Dubois and his group of musician friends stopped hosting shows there in the mid-1970s, but the memory of the musical space was kept alive by one of its founding musicians, Juma Sultan, who continued in tour. with Jimi Hendrix and have a successful music career. Now, at 79, he lives in upstate New York, and his archive of photos and documents from Studio We’s heyday have helped the museum tell the story of this site. He still plays concerts.

What is there now: The brick building is now a condominium with fivemillion dollar luxury lofts. One unit that sold in 2018 for $ 2.25 million featured beamed ceilings, reclaimed wood shelving and “exposed bricks whitewashed with Belgian limestone paint,” according to the listing.

The 55 engine barracks today.

Photo: Valeria Ricciulli

Wesley Williams, one of the first black firefighters in New York City, outside Engine 55.

Photo: Schomburg Center

Highlight: The fire station where Wesley Williams, one of the very first black firefighters in New York history, began working in 1919.

What is the story? Williams, who was from Harlem, was by no means kissed by his white colleagues: his colleagues didn’t want to eat with him and even left him once in a burning building. “He’s really kind of a trailblazer, not only to be one of the first black firefighters in town, but we can kind of see him as a predecessor of the civil rights movement because he faced extreme racism. upon entering the fire station, ”Lloyd said. Williams became the first black lieutenant in the FDNY in 1926, and was the second person in the history of the department to achieve a perfect score on the physical examination required to achieve this rank. He then co-founded the Vulcain Society, a fraternal organization for black paramedics and firefighters, dedicated to fighting discrimination in firefighters.

What’s left: The Engine 55 fire station remains largely as it was then, but nothing connects it to Williams. Rather, he is commemorated in Harlem, where there is a statue of him inside the Harlem YMCA , and the street it is on, 135th Street, was renamed Wesley Williams Place.