111 West 57th Street Earns Its Place on the NYC Skyline

It’s an uncomfortable thing to fall in love with a building you wish you didn’t exist. Of all the great towers that soared like flares, illuminating the city’s excesses and inequalities, 111 West 57th Street, designed by SHOP ARCHITECTS and erected by JDS Development, is by far the most thoughtful. As a statement, it’s infuriating; as architecture, it deserves its place on the horizon.

There is nothing new in this contradiction, of course. The powerful and the rich have doted the globe with splendor since power and wealth were invented, and the masses have seen these self-tributes with a mixture of resentment, gratitude and rage. New York is a global principality superimposed on a democratic metropolis, and if the capital’s lords are going to land here, their oversized palaces might as well inspire some awe. Mostly, they don’t. Christian de Port-zamparc A57 is repulsive. Gordon Gill and Adrian Smith Central Park Tower expresses the primacy of engineering over elegance. Rafael Viñoly’s cool symmetries 432, avenue du Parc charm some but provoke the fury of amateur critics. (Plus the elevators break down.) It doesn’t matter: the only audience for these companies is a small club of potential buyers who experience them from the inside out. SHoP’s 111, however, works hard to woo us all and be a good New Yorker. Or, as Gregg Pasquarelli, founding partner of the company, said, “If you want to build a building that 8 million people can see at any time, it better be really good. “

The object in question is nearly 24 times as tall as it is wide, making it by far the super tall slender in the world. This meant it could be sutured to the Steinway Building monument without swallowing it. (The narrow glass box that faces 57th Street as a commercial entrance only exists because zoning rules require it.) Thinness also applies to its shadow, which moves from n any location in Central Park within minutes. A small square of land supports 60 apartments, 14 of which are in the base, the others stacked like casino chips in the tower. If you spread these households over a dozen hectares, we wouldn’t call it grotesque inequality; we would call it a suburb. But in the heart of the city, the sky is a precious and limited resource.

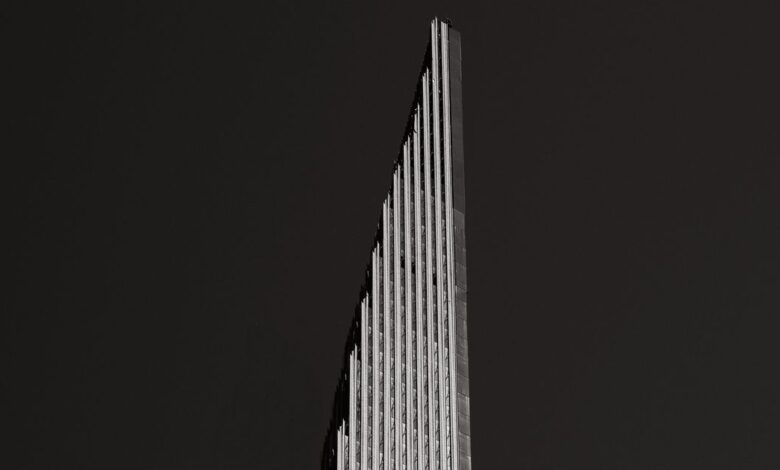

A century ago, the law that created the reverse side of New York City gave tall buildings the presence of three-dimensional carvings instead of so many frontage segments facing the street. But 111 is unusual in that the most flattering sides are its flanks, not its forehead. What holds the thing together is an H of massive concrete, solid to the east and west and open to the north and south. Seen from the park, it is a glass straw surrounded by brass. Look up a few blocks along 57th Street, however, and it transforms into a feathered feather, rippling shadows and narrowing into a sharp point. The success of the design is how it achieves that taper, shadows, and the sword-like combination of delicacy and strength.

Photo: Adrien Gaut

The saber hilt is the 1920s Beaux-Arts beauty of Warren & Wetmore which was once the home of Steinway, where Vladimir Horowitz and Sergei Rachmaninoff tested pianos. Much of the classical music world has disappeared from this neighborhood: managers, flacks and hopes; the Patelson Music House, where you could browse the symphonic sheet music sales bin and keep an eye on the Carnegie Hall stage door; the studios above the hall, where Bernstein, Brando and Agnes de Mille once lived with generations of wrestlers. If you could hear Russian on 57th Street at the time, it was spoken by a violist, not an oligarch.

SHoP literally dipped columns into the Steinway building, leaving the rotunda room intact, refreshing the limestone outside and renewing the copper roof. The pianos are silent, but the shell is more beautiful than when the place was animated with arpeggios. Time passes; the whole point of music is to mark its progress. Yet this kind of project virtually requires architects to engage with the past. The upper part of the old building is a patchwork of off-white bricks; the architects ordered six shades of cream for the facade of the tower. Terracotta and bronze embellish the obligatory glass, evoking both the Woolworth and Seagram buildings in counterpoint. These waves along the sides are set in motion by more than two dozen terracotta shapes, each a play of convexities and concavities that could have been extracted from the cornice of a Baroque church. When your eye is projected upwards, the sequence of these shapes creates an illusion of movement, an effect that will become more pronounced once the exterior lights are on. Like most fine ornaments, these shapes have a purpose: they disperse the wind in the same way that plaster in a 19th-century auditorium diffuses sound to give an orchestra that warm, intricate sonic glow. The pilasters drop one by one near the top, creating miniature recesses in a graceful curve.

Photo: Adrien Gaut

In his 1995 book, The form tracks finances, historian Carol Willis argues that despite the metaphors and cultural significance attached to tall structures, a skyscraper is above all an expression of the ability to pay for it and the promise that it will bring in money . Until recently, only large companies and business developers could raise capital or have the necessary liquidity. Then the world class plutocrats decided that storing big fortunes in airline real estate was a good investment. Like the art market, it was a self-fulfilling gamble. When the rich buy something, that’s what makes it valuable. A small number of sales, rather than a large volume rental, has become the surest way to cover the costs of shooting to the sky. Except that a floor space of $ 10,000 is functionally indistinguishable from the $ 2,000 version, and beautiful tubs can only increase the price to a certain extent. The only way to justify those hyper-super-ultra-luxury premiums is to provide a scarce, non-reproducible resource: an aerial view of Central Park and all the cute little behemoths below.

So, yes, the panoramas from the highest apartments are Olympian. The eye rises to the horizon far beyond the Rockaways, then descends to the bottom of the canyon. Shakespeare in the Park looks like a flea circus. (If you can’t afford this view, can I suggest a visit to one of New York’s many observation decks? Even a $ 75 ticket to the refurbished 102nd floor of the Empire State Building. seems modest compared to nearly a million times more.) Seeking an experience even a billionaire can’t afford, I climbed inside the steel trellis which adds 170 feet of empty space to the height – basically a crow’s nest made of ladders and platforms, open to the breeze. I can already imagine the first action movie finale to be filmed here with the loser floating in the void. Some will bubble up at the arrow like an icon of arrogance, pointlessly pointing to the heavens. I prefer to think of it as the gesture that completes the line.

Photo: Adrien Gaut

There is another option for a scout looking for dangerous architecture: the tuned mass damper. It is an 800-ton block of steel plate near the top, suspended from cables and plates in a separate chamber. When the wind blows in one direction, the counterweight swings in the other, keeping floors and stemware stationary. A few decades ago, trying to achieve that effect in such a pink building would have been a gamble that could have resulted in dancing chandeliers and a storm in the toilet bowl. Today, increasingly sophisticated computer modeling can predict how structures will interact over time. (On the other hand, technology hasn’t stopped 432 Park Avenue from whining like a haunted mansion.)

SHoP’s 111 has been in the works for years, of course, and if you think it may be a lavish relic in an age of post-pandemic modesty, the tea leaves suggest otherwise. Soon, a skyscraper so skinny you can practically see around it will be framed by the next generation of big colossi coming to the neighborhood around Grand Central. A Vanderbilt is already there, patting the Chrysler Building on the head like a little brother. SOM Park 175 is on its way. KPF’s 343 Madison isn’t far behind. And they won’t be the last. No tower will be the last, tallest, or tallest for a long time, but this one could be the best.