Rebuilding After Fire Requires Community-Level Thinking

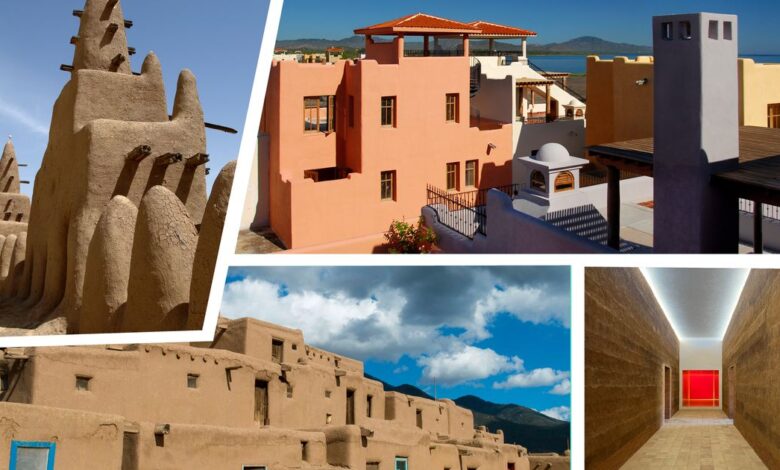

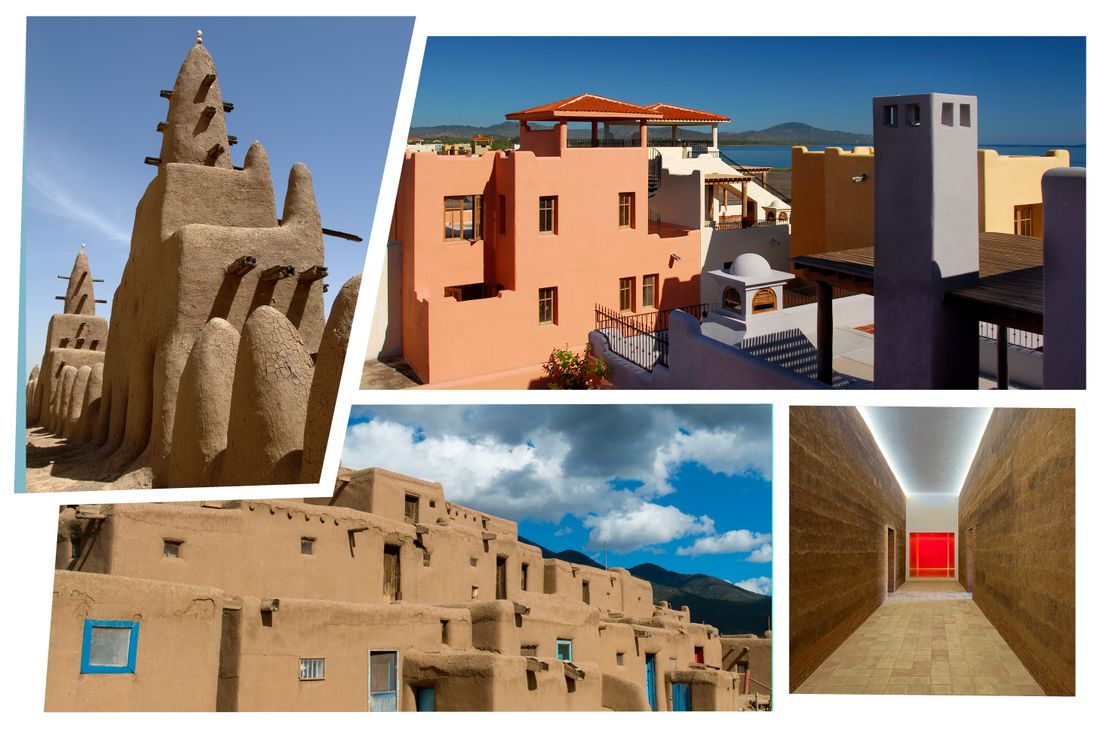

Clockwise from left: a mosque in Djenné, Mali; Loreto Bay in Mexico; detail of mansion by Juan José Santibañez; Taos Pueblo.

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos, clockwise from left: Michel Renaudeau/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images; Shutterstock; Justin Davidson; Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty Images

We all know that we are infuriatingly terrible at preventing the preventable. The calamitous fires that have swept out of the hills around Los Angeles, laying siege like an invading army in a pincer formation, spring from a mixture of natural phenomena and the human refusal to act on what we know. Wildfires are a special kind of disaster in that we are often the ones who light, feed, and propagate them. Flames pass from house to house, pausing for however long it takes to suck up all the energy stored up inside, furiously converting furniture, bedding, drywall, photographs, appliances, and diaries into carbon, heat, and toxic plumes. The longer a fire lingers, the hotter it grows and the more time it has to slip next door and start the process all over again. There’s an upside to this human agency, though: As suppliers of fuel, we have some control, not over a fire that’s currently burning but potentially over the next ones. We can’t placate an earthquake or deflect a tornado, but we can refrain from turning a small brush fire into an all-consuming conflagration — especially in areas that have already burned and will soon be ready to rebuild but will inevitably catch fire again.

“As long as we continue to build houses with wood in places that are expected to burn, the only outcome we can expect is that houses will burn,” says Michele Barbato, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California Davis. “We need to build noncombustible homes.”

Barbato believes that builders in Southern California and other fire-prone places should return to an ancient construction material that is plentiful, ubiquitous, indestructible, harmless to harvest, and easy to use: dirt. Earthen structures have a long and varied history: the hand-formed Great Mosque in Djenné, Mali; adobe churches, vertical villages, and new high-end mansions in Mexico. They have a reputation for frailty and for melting in the rain, but Barbato and his students have honed a technique of compressing soil into manageable blocks and hardening them with small amounts of cement. They have blasted the results with temperatures up to 1,800 degrees — as hot as a wildfire with 60-foot flames — for seven hours at a time. The blocks, which are cheaper, tougher, and more sustainable than clay-based bricks, remained impervious. They can be waterproofed with plaster, reinforced to withstand earthquakes and hurricanes, and manufactured on a vast scale with minimal environmental damage. “If you want structures that perform well against multiple hazards, this is a no-brainer,” Barbato says. “It’s safer and more sustainable, and it can be cheaper.” It can also yield genuine architecture: Nearly 25 years ago, the Burkina Faso–born German architect Francis Kéré developed a similar kind of durable, handmade earth-and-cement brick for a primary school in his home village of Gando. The project made him famous and contributed to his 2022 Pritzker Prize.

The adobe village of Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, has been continuously inhabited for over 600 years.

Photo: Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket/Getty Images

Juan Jose Santibañez’s Casa Esesarte in Oaxaca, Mexico, is made of earth and straw block manufactured by hand on-site.

Photo: Maria Esesarte

It may seem fanciful to require earth-block construction in high-risk areas, but we’ve made similarly radical changes before. American downtowns used to burn down regularly: Manhattan in 1835 and 1845, Chicago in 1871, Boston in 1872, San Francisco in 1906. And then they stopped. New rules prohibited wood construction and mandated fire escapes and industry-developed steel structures, engineers invented new fireproofing technologies, and municipal governments grew whole bureaucracies dedicated to safety. Now suburban-style areas burn, too, and our habits and laws haven’t caught up to our knowledge.

How to mitigate the risk isn’t mysterious. Chapter 7a of the California building code contains an exhaustive list of regulations for new building construction. The nation’s insurance industry offers a way to certify a Wildfire Prepared Home, and it comes with a clear and comprehensive checklist. Clear all vegetation from a five-foot buffer zone around the house. That wisteria spilling over the kitchen window? Begone. Clear the deck of wicker chairs. Toss the bamboo pergola. Install a solid door and metal threshold. Replace the wood-shingle roof with slate. And so on — a long, pesky, expensive list of fixes that will encourage fires to keep moving along like a burglar looking for an easy score. The goal is to keep flames from breaking into the house, say by cracking a window, lurking in a leaf-filled gutter, sneaking in beneath the siding, or slipping through an unscreened vent. “Once it’s inside, game over, the house is lost,” says Erica Fischer, a professor of structural engineering at Oregon State University. “Even if it doesn’t burn down, smoke damage is a massive issue.”

Armoring a house against fire can make it heavier and more rigid and therefore more vulnerable to earthquakes. “The materials we use to mitigate for fire weigh more, and earthquake demands are proportional to the mass of your structure,” Fischer says. “We need to be designing for multiple hazards.” Those design demands can be at odds. “If we only had fires, we’d do what Australia does and bury our electrical wires,” she adds. “But we have earthquakes, so we can’t do that.” Barbato’s compressed-earth blocks aren’t a magical solution to that conflict between fire and earthquake prevention: They’re best suited to one- or two-story buildings and, like all other materials, their seismic properties depend on carefully engineered designs. But properly stabilized and reinforced, they can create strong and ductile structures.

The resort village of Loreto Bay in Baja California, Mexico, launched in 2003, was big enough to need its own adobe-brick factory.

Photo: Shutterstock

Maybe the biggest obstacle to getting disaster prevention right is that it’s a collective need that depends on individual decisions about private property. Homeowners in Pacific Palisades, like affluent hill-dwellers in other parts of the West, will likely be able to rebuild quickly. They will no doubt spend fortunes on thick walls, triple-glazed windows, firebreaks, stone patios, Class A roofs, cement-plank siding, and fire-conscious design. The mobile-home park at the beach may not enjoy such luxuries. But owning a fire-resistant home is not the equivalent of installing a panic room or a blastproof bunker. It’s not a way for wealthy survivalists to retreat from chaos; instead, it’s an act of both self-preservation and good citizenship, like getting vaccinated against mumps.

The effort to reduce a community’s fire risk begins with defining the community itself. When it comes to defending against nature’s attacks, American towns and cities are hampered by a pastiche of jurisdictions: federal risk maps, state laws, local ordinances, homeowners’ association bylaws, insurance-company rules — all whirl together into a confusing set of incentives and obligations. One home on a street may have been given a disaster-defense checkup thanks to a town grant, but its next-door neighbor, just over the town line, may sit there just as vulnerable, and therefore dangerous, as ever. A burning house can shoot out embers that, lofted on powerful currents of air, can land and wreak misery several miles away.

Every fire disaster is a failure of civic organization, a deadly mixture of shortsightedness, misplaced frugality, and magical thinking. I asked Fischer if she knew of any places that handled the challenge correctly; she mentioned the city of Ashland, Oregon, where the deadly Almeda fire started in 2020. “The whole culture of the town has changed.”

I called Chris Chambers, the forestry officer who’s currently leading the effort to upgrade Ashland’s wildfire protection plan, and he told me that he was focused on protecting the part of the population with the fewest resources — many of them Latino immigrants who don’t attend planning meetings and don’t own the properties they live in. But even when people can pay for preparedness, they mostly choose not to. “If you got half of people to participate in a voluntary program, that would be a gigantic success,” Chambers says. He estimates that Ashland is 15 to 20 percent of the way to being fully prepared for the next Almeda. “It’s a surprising part of the human condition that we can stare a wildfire disaster in the face and then turn around and not take action on your own property when you’ve been told you’re at high risk. You just think: It’s not going to happen to me.”