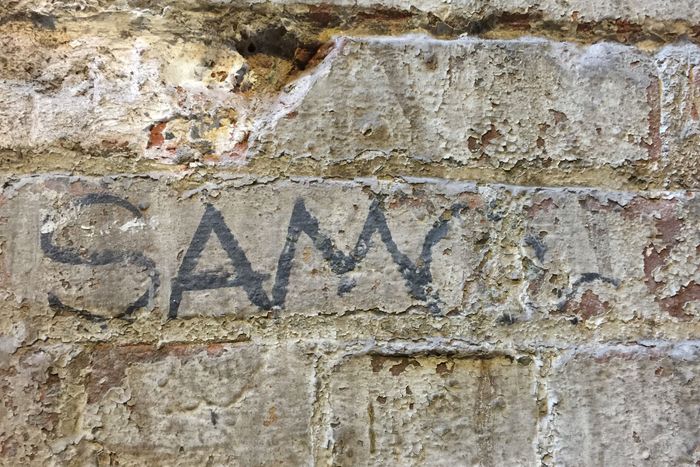

Basquiat’s SAMO Tags Appeared in This Williamsburg Loft

Documentary photographer Dona McAdams discovered this SAMO tag in the elevator shaft of 53–55 South 11th Street, a former factory where she had a loft, circa 1979.

Photo: Dona Ann McAdams

South 11th Street comprises two short blocks between Kent and Berry streets, just at the tip of Hasidic Williamsburg. “It was pretty much a ruin when I moved in,” says Jim Fleming of 53–55, the six-story factory-turned-artists’ lofts where he’s lived with his wife, Lewanne Jones, since 1982 Today, the building is generic. midscale real estate; the once sprawling lofts have been converted, for the most part, one- and two-bedroom apartments that rent for around $3,000 a month. The freight elevator loading dock that kept residents awake at all hours has been covered in cinder blocks, but you can still see its outline through the paint.

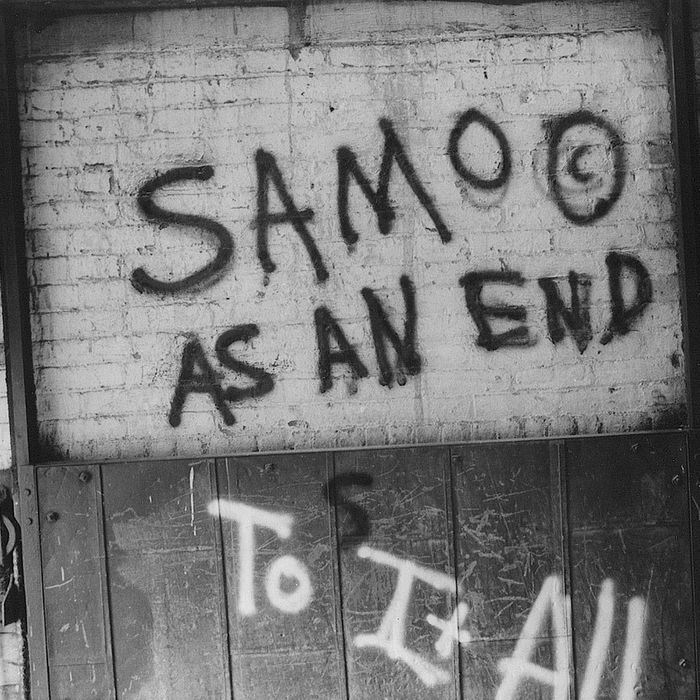

What you can’t see, say Fleming and Jones, are remnants of their building’s contact with New York’s art history. In the late 1970s, cryptic messages began to appear on city structures: “SAMO© AS AN END 2 THE NEON FANTASY CALLED ‘LIFE'” or “SAMO© AS AN END TO BOOSH-WAH”. In December 1978, the Voice of the village revealed that Jean-Michel Basquiat and a collective of friends and collaborators were behind the graffiti. (The newspaper called them “the new wave of Magic Marker Jeremiahs.”) The tags eventually made their way to 53-55, where they were scrawled between touchdowns. The writing was small, with the full label taking up about the length and height of a single brick. They were small curiosities, a story passed down between locals over the years. Tradition had it that Basquiat came to the building with Andy Warhol, “but it’s all potentially apocryphal,” Jones said.

The artist and archivist Henry Flyntwho created the first archive of SAMO graffiti and photographed the building some 25 years ago, Fleming once told he “lived in the Sistine Chapel” of accidental Basquiats. They didn’t last. After the building was sold in 2004, a renovation converted the industrial elevator into a smaller elevator and stairwell, forever burying each of the remaining SAMO tags in layers of paint and drywall. “When they put in the new elevator, it was like, ‘Oh, they’re so stupid!'” Jones says.

When Jim Fleming and Lewanne Jones moved into their Williamsburg loft in 1982, they noticed little SAMO tags on the walls of their elevator cage. Jones took this photo of a tag around 1990, before developers repainted it and installed an elevator around 2015.

Photo: Lewanne Jones

Prior to the renovation, evidence of the former occupants was everywhere: boxes of shredded $1 bills in the basement, which Fleming, an editor, used to wrap his books, and spindle bins. SAMO beacons have attracted the most attention. There was once a much taller one in the same elevator shaft that said, in letters at least two feet high, “SAMO© AS THE END OF EVERYTHING.” The documentary photographer Dona McAdams, who lived in the building in the late 1970s, remembers going on a trip and finding the graffiti when she returned. “It didn’t seem like a big deal at the time because it hadn’t been discovered,” she said. Sometime between McAdams’ departure in 1979 and Fleming and Jones’ arrival in 1982, these large letters were painted over and the smaller labels appeared.

As the neighborhood around 53–55 grew, new construction rising along the waterfront reduced the building’s view of the river. In 2004, the complex which comprises 53 to 55 was sold to Dov Land LLC and the longtime tenants found themselves at an impasse with their new owner. “Thanks to changes in the neighborhood and inflation and other market forces, rental values have increased,” said a Dov Land lawyer in New York Time in 2006. “The landlord, like any landlord who owns a building, wants to maximize rental income.”) Buyouts and other tactics to drive out tenants worked – many artists left. The building was split into two addresses, 53–55 and 65 South 11th Street, and the freight elevator that once served the entire building was converted into a passenger elevator for just 65. This, residents say, was the end SAMO beacons. “People came to see the graffiti,” said Jones, an archival film producer, but the owners didn’t care. (The building’s property manager did not respond to requests for comment on the graffiti cover-up.)

That’s more or less how it is in New York. Sometimes the losses are minimal; others feel impossible to miss. After a developer demolished 5Pointz – an abandoned factory complex in Long Island City that had become a graffiti mecca – to build luxury rentals21 artists won a nearly $7 million settlement for their work. There is now a set of commissioned murals on the side of the building facing the 7 train tracks that attempt, and spectacularly fail, to replicate the authenticity of the sublime art-covered structure that 5 Pointz once was.

Every once in a while, some famous murals are saved from the wrecking ball, like Keith Haring’s 1987 graffiti on a wall of the Boys’ Club of New York. Other times, they’re eaten up by the same forces through different means: A Haring mural that was removed from an Upper West Side youth center was sold at auction for $3.9 million in 2019.

Beyond their association with Basquiat, the SAMO beacons at 53-55 and 65 South 11th Street recalled a time when parties of 1,000 people continued until 6 a.m. in abandoned warehouses on the edge of the East River and where the artists and their neighbours, mostly working -class immigrants from Puerto Rico and Poland, could actually afford to live in Williamsburg and neighboring Greenpoint. Today’s building has nothing to do with what it once was. There are approximately nine renovated units on each level, the same amount of space that once housed two artists’ lofts, like the one Fleming and Jones share, which still has its original wood floors and exposed beams.

At first, the couple was nonchalant about the graffiti, but the tags have become special over the years. The former elevator operator proudly flagged them whenever someone new came in, and when news spread that there was a Basquiat in the building, people started coming just to see the tags. . You didn’t have to pay $35 (or $65 to skip the lines) to see a Basquiat; it was art history in the wild. “These things were a dime a dozen back then,” Jones says. “Honestly, you know, you could see that everywhere.”