How 6 Roommates Manage Their Communal House in Brooklyn

Members of the Harbor and some former roommates hanging out in the backyard.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

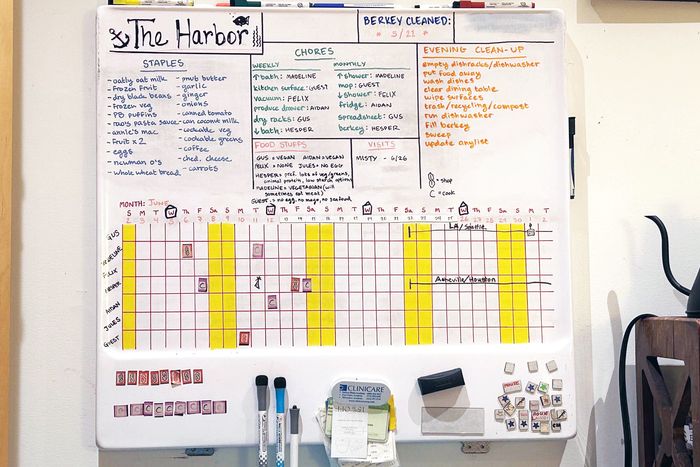

Wednesday evening is meeting night at the Harbor, a communal house on the border of Crown Heights and Prospect–Lefferts Garden. All six roommates gather around the round dining table in the kitchen, and, over a meal made by that day’s designated cook, they review the agenda — one created by all of them on a collaborative list-making app. First, they give kudos to anyone who had done extra for the house outside of their assigned chores; this week it might go to Madeline for cleaning the backyard. Then, some announcements: Aidan shares that his partner is coming to visit from out of town, so they know the house will be extra crowded for a few days. Jules asks that they declutter the downstairs hallway together after the meeting. And Hesper proposes a new dish-drying system, which they agree to try. Finally, they select who will buy the groceries and cook that week, and mark it all on a giant oven door that a former roommate salvaged from the garbage years ago.

Living in a cooperative house, for all its lofty ideals of shared resources and responsibilities, requires an infinite number of minute agreements to keep it running smoothly — I should know, as I’ve lived in several. In more conventional setups, a roommate who regularly fails to wash the dishes might get a passive-aggressive note on their door or have a tense conversation about it. In a communal house, this might spur a weekslong process of trying out different approaches to chores until everyone collectively agrees on one. In the end, some people realize their ideals about communalism are less important than having autonomy over their time or dinner menu, and that’s why many co-ops fall apart.

Hesper hadn’t planned to start a communal house when she moved to New York. When the 37-year-old arts therapist and her partner decided to move from Milwaukee to the city in 2018, they simply wanted to join one. “We didn’t want to be in this big, new city by ourselves,” she said. They had lived in a communal house in Boston while Hesper attended graduate school, and they liked always having other people around and cooking group meals. When Hesper’s partner got a job in New York, they looked at listings on the NYC Cooperative Housing Exchange Facebook group and Craigslist and applied to several. But all of the houses turned them down immediately because they didn’t have room for a couple. So Hesper posted a “wanted” ad on the Facebook group. She didn’t hear from any co-ops, but she did get a note from another couple who was also getting nonstop rejections, asking if they wanted to start a house together.

The pairs met a handful of times on Zoom. While neither had qualms about living with another couple, they wanted the group to have at least six or seven people to make sharing responsibilities easier. They agreed on what they wanted most: to be near green space and the train, and to establish processes like the weekly house meeting. In August 2018, without ever having met in person, Hesper and her partner sent the other couple several thousand dollars and signed a lease for a four-bedroom in Crown Heights. Then, they returned to the Facebook group (and Craigslist) to look for two more roommates. They narrowed it down to a woman working in journalism and the arts, and MJ, a 37-year-old luthier moving to New York for work.

They named themselves the “Harbor” — “a place to come home and rest before you go back into the world,” as MJ put it. Like many co-ops, they ask each member to commit to taking care of the collective needs of the house, from keeping all the common spaces tidy to clearly communicating when issues arise (no passive-aggressive notes). The “house love” committee figured out a system for chores, another committee figured out groceries and shopping (they decided everyone should join the Park Slope Food Co-op), and the third figured out how to schedule and track all these responsibilities (including the oven-door calendar and a spreadsheet for communal expenses). They decided to split groceries and utilities equally, and that each person would pay rent on a $800 to $1,200 sliding scale (couples and those who live in the light-filled upstairs rooms pay more). Each week, the roommates evenly divide three shopping trips and three group cooking nights among themselves, with Wednesday as the only night they typically eat together. These systems are flexible. Initially, the roommates used a “star chart” for chores, awarding themselves stars for completing tasks they had committed to and relying on visual pressure to stay on top of them. But when cleanliness became more of a priority, the roommates shifted to weekly and monthly chore assignments, and used the star chart to track when people took on extra tasks.

Hester preparing a meal for the group.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

The oven door that the roommates use as a calendar and chore schedule.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

But the space itself was a bust; there were mice in the walls, the apartment was falling apart, and their landlord did nothing to fix it. Three months in, they started looking for a larger apartment with multiple common spaces, and, in February 2019, moved into a five-bedroom duplex on the edge of Crown Heights and Prospect–Lefferts Garden, where they still live.

A year passed, and then the pandemic began. In the beginning, the group agreed to go into complete lockdown as a pod. But when vaccinations became available and the city’s collective COVID cautiousness eased, the group of six turned out to have drastically different risk-tolerance levels. Some people wanted to see a concert, or go on a date, or have friends over in the backyard. Others wanted to maintain strict protocols around masking, quarantining, and testing. They hashed out these decisions in their weekly meetings. Some of those conversations were long and exhausting, but people were “even-keeled,” said Gail, a 31-year-old public-health worker and former roommate who lived in the Harbor for over two years. When someone wanted to go to the gym and another preferred everyone stick with at-home workouts, the whole group discussed ideas for how to resolve the difference. “Instead of being an argument between two people, we were able to mediate each other,” said Gail. (In the case of the gym, the group came to a compromise that their roommate could go to a nearby, low-trafficked gym and work out in a KN95 mask.)

Aidan in his room at the Harbor.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

Madeline in her room.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

Jules in his room.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

Still, five people left over the course of two years, which was more attrition than average. This included MJ, one of the earliest members, who left at the start of COVID. She couldn’t work from home, and both the house and her boss asked her to pick just one COVID pod. She ultimately moved in with her boss. The following year, Gail and her partner, Taylor, a 31-year-old data analyst, moved out because they wanted more space; with their hybrid jobs, they couldn’t really work together in their bedroom. They also had the more mundane wish to have friends over for dinner — something they could do at the Harbor, but never in private. “If the Harbor was in a different configuration or we had more space, we would have stayed,” said Gail.

The close quarters remain one of the biggest challenges for the six who live there now. When everyone is home, it can feel pretty cramped. (Only Madeline, who has seven siblings, said she isn’t usually bothered by it). The apartment is big by New York standards, but there are only two common areas: the upstairs kitchen, which has a nook for a dining room table but can’t handle more than two people cooking at a time, and a basement common area that has a couple of assorted couches and tables. There aren’t strict rules on what can be done in the common spaces, and there’s an understanding that the roommates can use them together. If Madeline is journaling at the dining room table, Aidan, an M.F.A. student, can still set up to paint there, and likewise, if Jules is studying for his social-work degree downstairs, Hesper can still come down to read a book. They also have a backyard, where they garden in raised beds and host dinners during the summer. To maximize storage, they installed wall-hanging kitchen storage and bookshelves in the downstairs hallway. Still, someone is always moving around something or someone. “A lot of points of friction between us are related to the fact that we’re six people living in a very small space,” said Aiden.

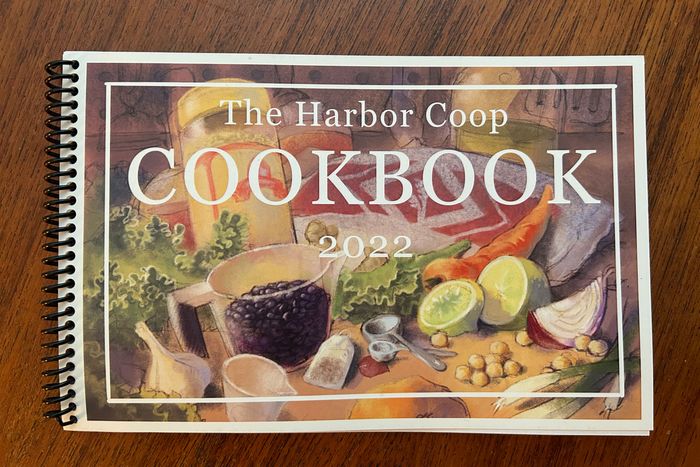

The group compiled a book of their tried-and-true recipes, including some from an era where members were gluten-free, soy-free, and vegan.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

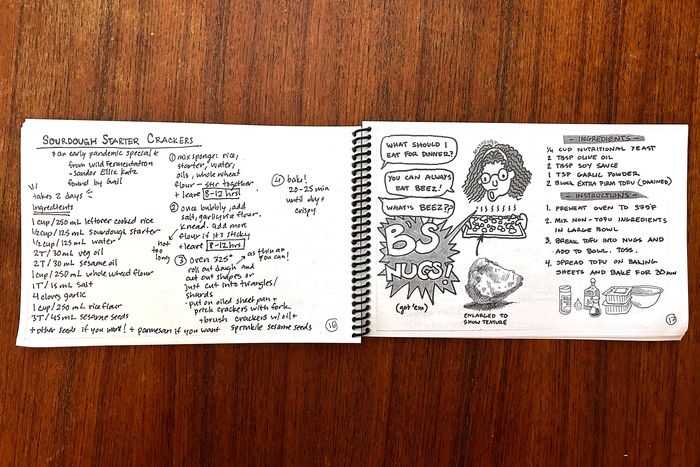

A recipe for sourdough starter crackers that roommates made regularly in the early days of pandemic, and one for tofu nuggets, with illustrations.

Photo: Photo by Harbor Group

In such a crowded house, even the smallest of disturbances can quickly get magnified. A couple of months after he moved in, Jules kept getting woken up by someone walking around the kitchen above his room. He brought it up at a house meeting, and Aiden immediately confessed. “I’m a stomper,” he admitted. Together, the house brainstormed some solutions. One roommate suggested putting a “no stomping” note on Aiden’s door — but it didn’t work. Later, someone else encouraged Aiden to wear Crocs indoors — and the thudding sounds were gone. “Small things turn into bigger things when people don’t talk about it. Then, one day, someone explodes and is like, ‘You’re so loud!’” said Hesper. Noise is a source of tension in all the rooms (those living upstairs are by the kitchen and more prone to hearing the front door slam), so they put in place a process for closing the door without making it slam.

Who gets light and who doesn’t also poses another set of issues. At the height of the pandemic, Aidan felt particularly claustrophobic in his basement room, where he also worked from home. It began to affect his sleep and make him anxious, so he brought it up at a house meeting, and Taylor suggested factoring sunlight into the sliding scale cost for each room (a calculus that’s still in place today). “It was less than a hundred dollar difference in the monthly rent, but I felt heard and like people were invested in solving my issue,” said Aiden. He’s since moved upstairs.

But it isn’t all trade-offs — there’s an unexpected perk of living in the house, which they call the “Extended Harbor.” It began as a group chat started by Gail and Taylor when they left, and it has since expanded to a group of 13 people that includes current and former roommates who live nearby. On the chat, they keep in touch and trade favors: Aiden goes to MJ’s place (affectionately called Harbor South) to use her printer; Jules cat-sits at Gail and Taylor’s apartment (Harbor North) despite never having lived with them. “It’s not the same as the default intimacy of seeing each other every day, but they’re still highly involved in my life,” said Taylor. It works the other way too; Gail often stops by Harbor Central (the main apartment) to mend her clothes on someone’s sewing machine and sometimes stays for dinner. And they all go on an annual retreat upstate together, renting a house and organizing activities around a theme. This porousness between old and new members was a “green flag” to Madeline before she moved in. “It’s not like people are leaving angrily,” she said.

Hesper and her partner are now the only founding members of the Harbor still around. It helps that the current group gets along particularly well (a sentiment they all agreed on). Seven years in, Hesper still enjoys always having people around, even if they’re just in the same room doing different things — a concept she calls “passive socializing.” Once in a while, she wishes she had more space, but whenever she pokes around online, she’s shocked by the rates for one- and two-bedrooms. The Harbor has also searched for a bigger space for their collective but hasn’t found anything bigger or better, at least anywhere near the price of $1,200 a person, the maximum rent a roommate pays.

As for the roommates who’ve left, they say they keep some house traditions alive in their current arrangements. MJ and her roommate (an honorary member of the Extended Harbor who never actually lived in the house) now use a system for tracking chores that they learned from the house. Gail and Taylor make collaborative grocery lists and share once-weekly meals with their downstairs neighbors. It’s not as communal as they’d like, but it still feels Harbor-esque. “These systems really helped us know how to communicate and how to live,” said Gail. “However we live in the future will be very shaped by what happened there.”