Jamaal Bowman Proposes A Green New Deal for Public Schools

Photo: Michael M. Santiago / Getty Images

Until this summer, Hamilton School, a public elementary school in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood of West Philadelphia, was surrounded by asphalt. Now some of the bitumen has been torn to make room for three raised beds that will grow vegetables and medicinal herbs like chamomile and mint. Gardeners also plant fruit trees around the perimeter of the school. The hope is that in a few years the neighborhood will be able to pick pears and fresh apples from the trees whenever they want. It might seem like a small change, but Cobbs Creek’s health outcomes rank among the worst in the city, and residents have a median income of $ 30,500. “It costs $ 120,000 at most, but it pays so much,” says Akira Drake Rodriguez, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania whose graduate students are working on the project, which will also be an outdoor classroom. “It started out as an eco-friendly stormwater project, but the school kept stacking things up. “

Harrity School, a public charter elementary school just a ten-minute walk south of Hamilton, could also benefit from green space and gardens, but the administration is too small there to look for grants or local organizations to collaborate. to such projects. “Harrity has to wait for his fairy godmother to give him the same amount [of money]”says Rodriguez.” We can’t scale this project up. It works, but we can’t scale it. The improvements in Hamilton have indeed required a lot of outreach and organization: the Philadelphia Food trust, the Orchard project, the Environmental Protection Agency, and Penn all provided funds or labor to make the school gardens.

The uneven and disparate way schools find the resources to green their schools could end in a new federal policy. On July 15, Jamaal Bowman, representative of the 16th Congressional District of New York, introduced the New Green Deal for Public Schools Act, a bill that would provide $ 1.4 trillion for climate resilience and decarbonization initiatives in K-12 public schools. Like previous Green New Deal bills, like the social housing law introduced in 2019, Bowman’s initiative calls for a mix of workforce development and capital improvements with an emphasis on directing investments towards frontline communities, who suffer the greatest consequences of climate change and environmental injustice due to poverty, racism and historical exclusion. Conceptually, the bill redefines public schools – which have never been adequately funded by the federal government – as the lifeline of a community.

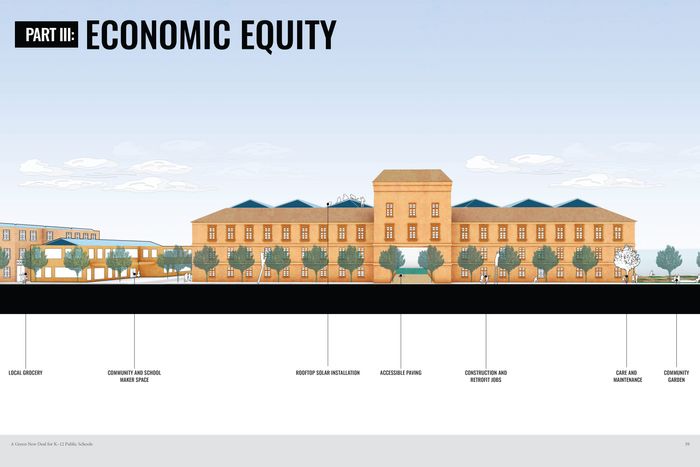

The Green New Deal for Public Schools emphasizes three types of equity and creates funding mechanisms to achieve them. Environmental equity is like clean drinking water, clean air and carbon-free energy. To this end, infrastructure such as solar power on rooftops, LED lights and sanitation of toxic materials in schools.

“Our goal is to see schools as a critical infrastructure in the neighborhood,” says Rodriguez, who also co-wrote a report analyzing the potential impact of Bowman’s bill. “It means investing in schools the same way you would invest in roads and utilities: it’s something that won’t always pay off, it’s something that is informed by local values and customs. “

So what might the Green New Deal for Public Schools look like? It could be used to fund this garden in Harrity or pay for the removal of lead, asbestos and mold in any of the dozen of Schools in Philadelphia that have toxic environments and have suffered from years of divestment. It could be used to add solar panels and LED lighting to help one school reduce carbon emissions, or equip another with energy storage in the event of a blackout. It could be used to turn schools into relief centers during extreme weather events like heat waves, storms and floods, such as St. Martin’s Parish School in Mississippi, which was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina and rebuilt to emergency shelter standards using FEMA money. The bill also allows schools to distribute food, energy or other basic needs on an ongoing basis. Local districts are able to prioritize their needs because the bill does not prescribe a unique formula for each school.

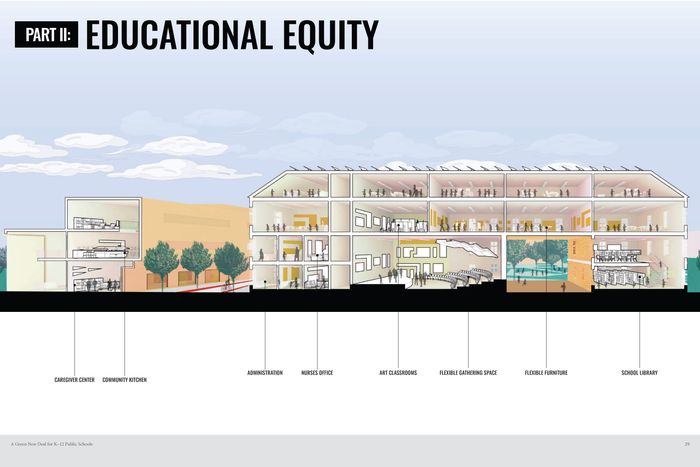

School resources are scattered across schools in frontline communities, so the bill also addresses educational equity by funding administrative and teaching positions, new curriculum development and materials. educational like books. Having good health units for students, staff and communities is also part of the proposition.

Some schools are already serving de facto as community centers and disaster relief centers, but the Green New Deal for Schools sees schools as a central part of the process. community resilience, which aims to address some of the chronic issues that make communities vulnerable in the first place. It shortens the time a community needs to recover from a disaster and responds to the reality that daily conditions are already at a crisis level. “It’s useful to centralize, but when we think of a community hub, it’s more like a hub and shelves,” says Rodriguez. “The school is a center, but it sends resources to a neighborhood and brings them in. To this end, the bill funds community needs beyond schooling, including programming and staff to facilitate connections to parks, libraries, health centers, daycares and resource centers for the use. The bill would also fund 1.3 million jobs in construction, maintenance and educational resources each year.

And that money is essential. Less than 10 percent of a school’s budget comes from the federal government. Almost half comes from local property taxes, which reflect the legacy of segregation and redlining, and the rest comes from public funds. Chronic disinvestment in public goods has deprived all but the richest schools of resources. America’s Richest 10% School Districts spend three times more than the poorest 10 percent districts, while schools with higher concentrations of poor and minority students receive less funding than other schools in the same district. The bill specifies that school districts in low-income areas will receive funding first.

Economic equity is the third pillar of the Green New Deal for public schools. The implementation of the policy would generate around 1.3 million jobs per year in construction, maintenance and education. The bill also calls for the creation of a kindergarten to higher education pipeline to prepare people for these positions.

Ultimately, the goal is for everyone who lives in a neighborhood to benefit from Green New Deal funding for public schools, not just students and teachers.

“The Green New Deal holistically thinks about how a school might serve the neighborhood instead of the district budget, the state budget or real estate values,” Rodriguez said. “The power and potential is finally creating a public school that everyone cares about, and I can’t say we’ve done that before. “