Mel Gussow’s Village Row House at 28 West 10th Street

Until his death in 2005, the theater critic Mel Gussow spent most mornings writing reviews and profiles in an office in the rear of an 1856 rowhouse on West Tenth Street, where bookcases stretching up to 13-foot-high ceilings wrapped wall-to-wall, skipping only a marble fireplace. His low desk was shoved into the corner furthest from the windows, as if Gussow had wanted to muffle the city’s distractions. But this wasn’t a life of drudgery; Gussow was at the theater five or six nights a week, often taking his son Ethan with him. On Wednesday evening, Ethan Gussow, sorting through moving boxes full of books and papers, showed me a framed photograph of him and his father, both of them laughing as Mel tugged the false, pointy beard of Zero Mostel, in costume for a revival of Fiddler on the Roof.

The office is on the uppermost floor of an owner’s triplex that extends two floors down, into an English basement with an even deeper literary history; these rooms were once Dashiell Hammett’s, where he wrote detective novels and screenplays before he was sent to prison in 1951 for refusing to testify during the McCarthy era. Other literary tenants who might have chatted with Hammett in the hall were Jane and Paul Bowles, known for their novels and their unconventional living arrangement. As Gussow explained in Paul’s obituary, Jane was a lesbian, Paul was bisexual, and they stayed on separate floors: her on the third, him on the fifth, and between them a stage designer with whom they shared a cook.

The Bowleses had ditched New York for Tangier, Morocco, more than a decade before Mel Gussow’s parents bought the building in the 1960s for around $60,000. At that time, the tenants included Marcel Duchamp, who as the story goes had moved in to be closer to the chess club across the street. The Gussows had bought the building as an investment — not for their son to live in.

But Mel and his family ended up there in 1971, due to an accident of history. Ann, a freelance editor, had married Mel in 1963, and they had taken an apartment nearby on West 11th Street. On March 6, 1970, when none of them were home, a bomb went off next door, killing three of the members of the Weathermen who had helped make it, destroying the house above, and destabilizing many lives. The building where the Gussows had been living was condemned. But Mel didn’t want to leave the neighborhood. In a 2000 remembrance of the blast, he described the streets between Fifth and Sixth, north of the park, as a “haven in a city that thrives on its hyperactivity.” He turned to his parents, and they rented him the Hammett duplex.

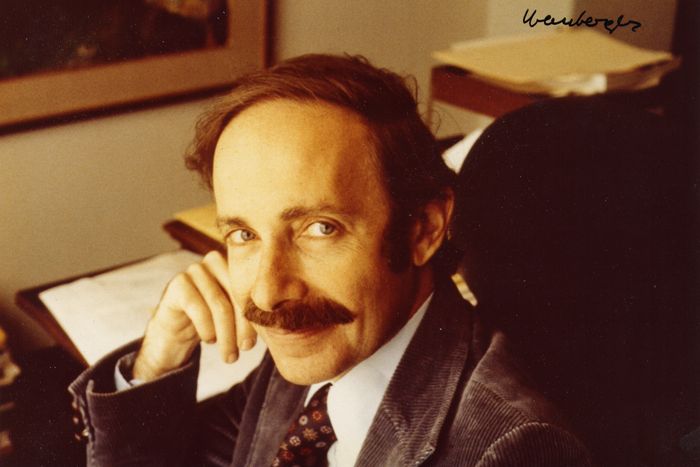

Mel Gussow at his desk.

Photo: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

The duplex was empty, but it had been painted black and had an odd layout that put a bathroom in the center of the living area. The Gussows renovated, pushing that room under the stairs and adding a full kitchen, which they kept open to the dining room and living area — the better to host dinner parties that would draw a rotating cast of theater-world greats, including Tom Stoppard, John Guare, and of course Mel’s close friend Edward Albee. Then there was V.S. Naipaul, who would come over when he visited New York. Once, when the family was away, a young John Malkovich and Glenn Headly house-sat. Wherever there was space, they added bookshelves.

The foyer. Renwick curved walls around the stairwell, which he pushed to the center of the house, allowing rooms at the front and back to stretch the full width of the home.

Photo: Travis Mark

Upstairs, the parents’ bedroom looks over a quiet, paved garden where they’d often eat lunch. Ethan took the room at the front of the house on the first level, with a window seat and a view over Tenth Street through a wrought-iron window guard — a quirk of this particularly enviable row of townhouses. Designed by James Renwick Jr., whose trademark was to collage together many different architectural styles, the Gussows’ home was part of an entire row of houses on what is sometimes called “Renwick Row.” Here, the architect had scaled the row of homes on West Tenth to squeeze more buildings onto land that was becoming more expensive, explained historian Patrick Ciccone. At 18 feet wide and a high-ceilinged four stories high, each house might have seemed awkward and gangly — but Renwick avoided the problem with an optical trick: a horizontal stripe of wrought-iron terraces that unifies the façades to create the illusion of a single grand mansion. Inside, the rooms feel wide thanks to his decision to get rid of a stoop and instead pull the staircase into the windowless center, so windowed rooms at the front and back stretch the full width. “I always point these out as, ‘Here’s an alternate reality for New York, if people in the 1850s realized this was the more rational way to build,’” said Ciccone.

The step up from the English basement, where Dashiell Hammett rented, into a small yard. Ethan Gussow would play here as a child, and it’s where his parents served lunch in good weather.

Photo: Travis Mark

The homes were designed for single families, but as tony New Yorkers moved uptown in the 20th century, the buildings were chopped into apartments that eventually lured the Greenwich Village bohemian set. Albee lived a few doors down. So did the actresses Kathleen Turner and Rose Gregorio, and Thomas Meehan, who wrote Annie. When Don Gussow died in 1992, dividing the building among his heirs, Mel Gussow bought out the others and became the landlord. When Duchamp’s widow passed away, it was up to the Gussow family to find another renter, who ended up being Martha Clarke, the dancer and choreographer. “She was thrilled it was Marcel Duchamp’s apartment,” Ann remembered. When she changed the locks for Clarke, Ann kept Marcel Duchamp’s keys — a landlord’s readymade.

Another Duchamp will likely not be renting here again; the broker predicted it would go to a wealthy buyer who would join the rest of the block in converting it back into a single-family residence. At the moment, only one of the other ten rowhouses is divided, and two are now actually being combined — along with a carriage house — by Facebook mogul Sean Parker. The money has changed the feel of the block where Ann and Mel would often run into John Guare walking his dogs. Neighbors don’t always say hello, Ann said. “So I always say ‘hi’ to the dogs.”

An original fireplace on the third floor, in a rental unit. Tenants over the years included Paul and Jane Bowles, Dashiell Hammett, Marcel Duchamp, and Martha Clark.

Photo: Travis Mark

Original crown moldings from 1856. As the landlord, Ann Gussow found herself directing renovations for rental units. “I liked to have rooms as simple as possible, so that the people who lived there can do what they want to do with it,” she said.

Photo: Travis Mark

Renwick’s central stairs curve, and even include niches for displaying statuary. Here, a curved closet door in a rental unit carries Renwick’s motif.

Photo: Travis Mark