For Fire Victims, a Year (and Counting) of Waiting In Limbo

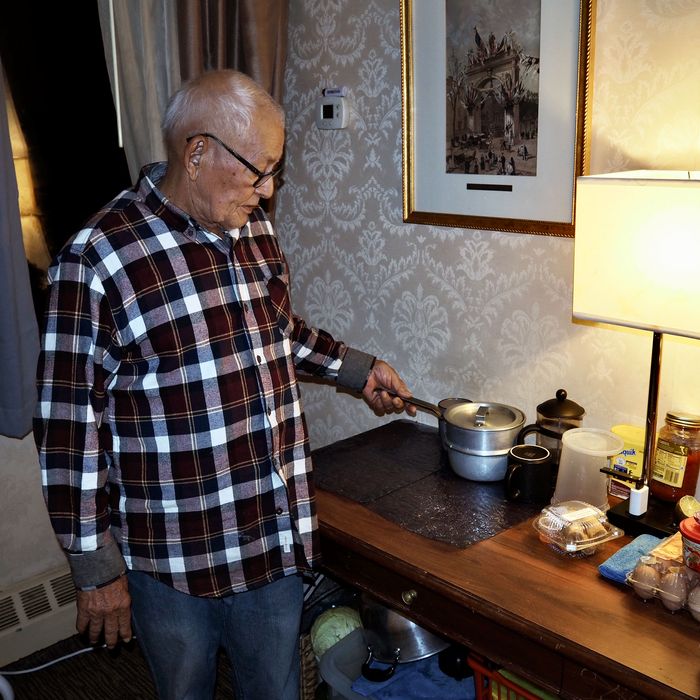

Antonio Rojas oversees his makeshift kitchen at the Airway Inn.

Photo: Amir Khafagy

Less than a mile from La Guardia Airport, on a stretch of Astoria Boulevard dotted with auto repair shops, gas stations and fast-food chains such as Popeyes, stale cigarette smoke permeates the hallways of the Airway Inn and the carpets are covered in grime. Inside the motel room where Patricia Rivas, 76, and her husband, Antonio Rojas, 87, have spent the past year, Rivas points to mold growing on the ceiling. In a corner, next to the television, the couple have set up a makeshift kitchen with a hot plate. Rivas, who uses a walker, constantly bumps into it as she moves around the bed. As the two talk, they continue scratching their legs and arms. Rojas rolls up his pants to show rows of bed bug bites.

This is not how they imagined they would spend their retirement years. Since a eight alarm fire destroyed part of their six-story building on 89th Street and 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights last April, Rivas and Rojas were unable to return to the three-bedroom apartment they had lived in for 49 years. Fire, sets off by an overheated power strip, injured 21 tenants and left nearly 500 homeless. Rivas and Rojas, along with more than 40 other families, are still waiting to return.

One floor above Rivas and Rojas, Jose Rodriguez and his girlfriend are also among ten 89th Street families who have been placed in the motel by the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. In their small room, a pair of gregarious Sun Parakeets twirl freely around the room, while a pair of more timid Parakeets stay close to the cage. As a child, Rodriguez often passed by Rivas and Rojas’ apartment to play with their son. For a time in the 1990s, he even served as the building’s superintendent. Now the 50-year-old just wants to return to the house he fought for after his mother died during the pandemic (the rent is a very affordable $157 a month). Although tenants who live on Airway have tried to check on each other, Rodriguez said they can’t replicate what they once had. “That’s how the building was – everyone knew everyone,” he said.

Away from home, Rivas yearns for the landmarks of her daily routine: the Colombian bakery where she got her café con leche, the Trade Fair supermarket two blocks from her apartment. The nearest Airway metro station is a half hour walk away. “We’ve run out of money,” Rojas said; both are retired and live off their social security contributions and modest pensions. “I spend money every day to eat out, and it’s hard.”

An 89th Street apartment destroyed by the April 2021 fire.

Photo: Andrew Sokolof Diaz

Since the fire hadn’t burned down their side of the compound, Rivas and Rojas figured they would only be away from home for a few days. But the Department of Buildings found structural damage, along with lead and asbestos, and issued a release order for the whole building. A mold problem quickly developed. The building has since been covered in scaffolding, but Rivas and Rojas aren’t sure exactly what the owner, Kedex Properties, actually fixed. Two months after the fire, the city’s housing agency issued 131 housing code violations to Kedex for unrepaired damage. They make up nearly half of 309 open violations that the owner has accumulated in his 17 properties. But issuing violations didn’t seem to spur much improvement – which isn’t rare. In July, HPD filed a court case against Kedex for failing to correct construction violations. The following month, 60 tenants for follow-up the owner and HPD.

Kedex Properties owner Jorge Bolanos did not respond to questions about why he had racked up so many violations and insisted he was in communication with tenants. “The only thing I want to tell you now is that we want to fix the building and have them back as soon as possible,” he said in February. “But, unfortunately, they are misled and misinformed.” When asked who was misleading the tenants, he refused to answer and abruptly hung up the phone.

In November, the judge presiding over the trial of HPD order the owner to pay HPD a fine of $34,000 and gave Kedex a detailed schedule of demolition and renovation deadlines. It also released a date when residents should be able to move in again: January 2023, nearly two years after the fire.

Andrew Sokolof Diaz, president of the building’s tenant association, believes Kedex is intentionally delaying repairs. “They’re going to drag this out and wait until we get tired,” he said. He worries that the longer the repairs take, the more likely his neighbors will give up. Diaz himself is ready to fight for another year if he has to, but he knows the rest of the tenants might not be able to make it. “If it takes three years to rebuild, no one will come back,” he said. Some residents have already moved. Many have found new apartments and some have even left the state. Tenants who held out hope of a return to 89th Street have renewed their leases and continue to pay the landlord $1 a month in rent. But it’s unclear if the owner will guarantee that the holdouts will have a place to return to.

The relationship between tenants and landlord has been contentious for years. Diaz said when residents protested Kedex’s 2017 attempted rent increase, the landlord threatened undocumented tenants with eviction and eviction. “My neighbors were telling me the landlord was pressuring them by using their immigration status against them,” he said. “They were scared.” In response, residents formed the 89th Street United Tenantsstarted a petition, organized protests and were able to stop the rent hikes.

The move-in deadline imposed on Kedex is still seven months away. The long wait shows how ill-prepared the city is to hold landlords accountable after a fire, some housing attorneys say. “There are mechanisms in place to house people in an emergency,” said Justin La Mort, an attorney with Mobilization for Justice, an organization that provides legal services to low-income New Yorkers. “There are fewer mechanisms in place to ensure buildings are repaired in a timely manner.”

Construction of the 89th Street building in February.

Photo: Amir Khafagy

To date, the first wave of public support and media attention for displaced tenants, including a GoFundMe that has raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for them, has faded. Like the residents who survived January’s catastrophic fire at Twin Parks Tower Northeast in the Bronx, most Jackson Heights residents are working-class immigrants for whom market-priced housing is largely out of reach. They are also the most vulnerable to fires – most of the city’s roughly 2,200 fire calls each month come from neighborhoods such as Jackson Heights and the Bronx, according to a Documented NY report. The city has just adopted a slate of bills to improve fire safetybut they offer little for tenants like Rivas and Rodriguez.

For now, Jackson Heights tenants plan to wait at the Airway. But it’s unclear how long HPD will continue to cover the Airway Inn fee, which is estimated at $125 per night. Rivas said she had been getting calls from HPD Rep. Jessica Ortega for months, urging her to find an apartment and move out. When reached for comment, Ortega declined to speak and HPD press secretary Jeremy House denied that the agency pressured the families to leave. Typically, the city provides only a few days of emergency housing for fire victims, the agency representative said. “They can stay in the HPD family shelter until they can return home or find new accommodation,” he said. “A long-term housing plan is in place for all those registered for HPD support. »

But the couple don’t want to go to an HPD family shelter. On the one hand there is no such shelters in Queens, and they do not want to live temporarily in another district. For long-term housing, HPD offered all tenants Section 8 coupons, but like many landlords discriminatede against voucher holders and enforcement against those who do is lax, they haven’t helped everyone. Even if Rivas and Rojas could find an affordable apartment on their own, they fear that if they sign a lease for a new apartment, they will lose the right to return to 89th Street. In addition, their old apartment cost $780 a month, a rent that would be almost impossible to find now. “They’ll try to charge us $2,500, and we can’t afford that,” Rivas said. Their fixed income, along with their need for an elevator and an accessible entrance, severely limits where they can travel.

“We have an affordable housing crisis and we don’t have any vacant public housing,” said La Mort, the housing attorney. “So when you have a crisis like a fire, when you have a large number of people suddenly facing homelessness who have never been in this situation before, it challenges both the social safety net and our courts. .”

Asked more recently about his plans for tenants who want to return, Bolanos said: “It’s nobody’s business, first of all.” He added that the trial had prevented him from speaking further.

The limbo that Jackson Heights tenants find themselves in is now shared by twin parks fire survivors, who have also been placed in run-down motels and see no clear path to stable affordable housing through city agencies. When the spotlight inevitably goes out, it seems the victims of the city’s fires are too often left on their own, with only a patchy network of nonprofit organizations to fall back on. At the Airway Inn, Rivas and Rojas get tired. Although Rivas is grateful to have a place to live, the months of coping at the motel have been exhausting and isolating. “We feel like animals locked in a cage,” she says.

Patricia Rivas sits on her bed at the Airway Inn.

Photo: Amir Khafagy