Where Is Our Post-Car City?

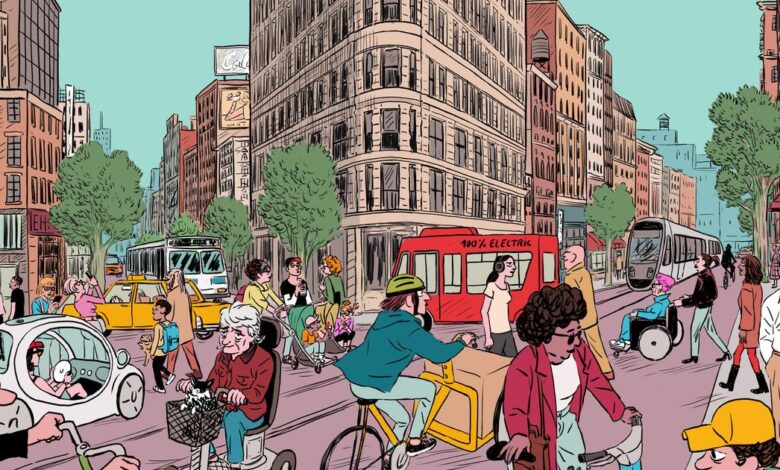

The city we could have. (Scroll down to see the similar vibrancy of this intersection a century ago.)

Illustration: Javi Aznarez

Years ago, one of the many storms that periodically flood Riverside Park cracked open a playground’s paving. The sinkhole has gone unrepaired since then, and it’s grown deep and wide enough that a bear might choose to hibernate in it, curling up beneath the trees that have taken root in the cavity. The scene, with the rusting frame of a tire swing above and crowd-control barriers all around, could be an establishing shot for a film about an abandoned metropolis: one of the country’s great parks collapsing into itself. The playground will be rebuilt someday, though by then it may have sat, cratered and unused, long enough for toddlers to have grown into tweens.

In the meantime, it sits like a wrecked mini-microcosm of a city unable to keep up with decay and with no time for the future. The public realm, the 40 percent of the city that we all collectively own, is a Swiss cheese of neglect and procrastination, seasoned with stalled projects, discarded plans, and out-of-date uses. The city feels stuck and sluggish, prey to an uncertainty that’s especially acute in the spaces we all share. Pedestrians scoot past agitated mutterers or calculate their chances of survival before stepping into a crosswalk. Subway passengers — and there are still nearly 25 percent fewer of them than in 2019 — nervously keep their backs to the platform wall.

In midtown and below, congestion pricing is helping to thin traffic and smooth the way for the buses that, in the rest of the city, still inch agonizingly along. It’s a good start but not enough. For New York to endure as a global capital, it must definitively rebalance power in the streets, not just in high-density Manhattan but in Crotona, Hunts Point, and Canarsie, too. We know what a post-car city could look like, since parts of it were mapped out in detail before the future got indefinitely postponed. As you wend your way to La Guardia, spare a thought for the N-train extension through Astoria straight to the airport, an idea that was first floated in somewhat different form in 1943, fleshed out and partly funded in the 1990s, and finally scotched, largely because of local opposition, in 2003. Two decades later, a different much-debated, ever-more expensive dream of a La Guardia AirTrain was quashed too. Has any other city ever had a higher ratio of plans to finished projects? The coming mayoral election presents a chance to sort through the big basket of proposals, feasibility studies, reports, and designs; pluck out the promising ones; and stop shrugging and sighing that it’s all so hard.

The pandemic effectively killed then Mayor Bill de Blasio’s two most transformative construction projects (both of which were already looking shaky): the Brooklyn-Queens connector, or BQX, and Sunnyside Yard. The first was a streetcar line from Sunset Park to Astoria. The premise was sound. A new above-ground transit line would serve the tens of thousands of residents who have settled along the waterfront and in Downtown Brooklyn over the past two decades. Yet the project immediately ran into a barrage of sometimes contradictory objections. Laying tracks would mean moving underground pipes and cables — once workers figured out where they were. The streetcar would move too slowly, carry too few people or too many, be obsolete on opening day, cost too much, and trigger gentrification. It should really be a bus. It should definitely not be a bus. The administration hired a light-rail expert from Toronto, Adam Giambrone, to cut through that knot of negativity. “We have eight years to get this built,” he said. That was almost nine years ago; Giambrone now consults on and manages transit projects in Saudi Arabia.

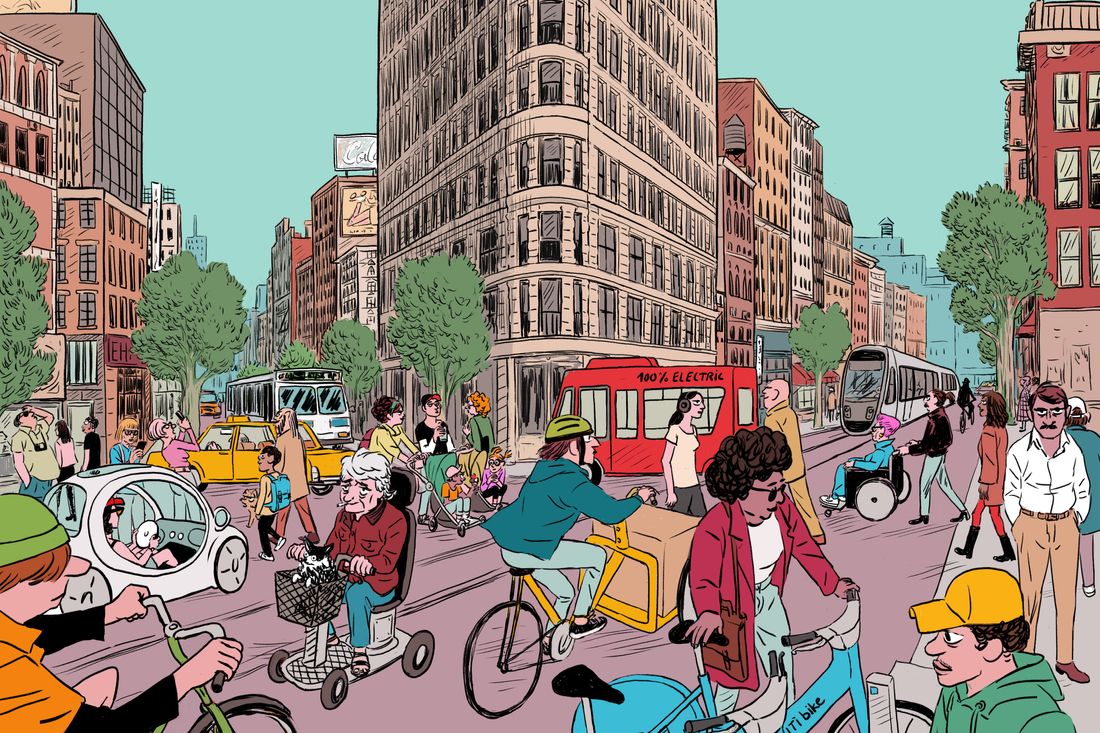

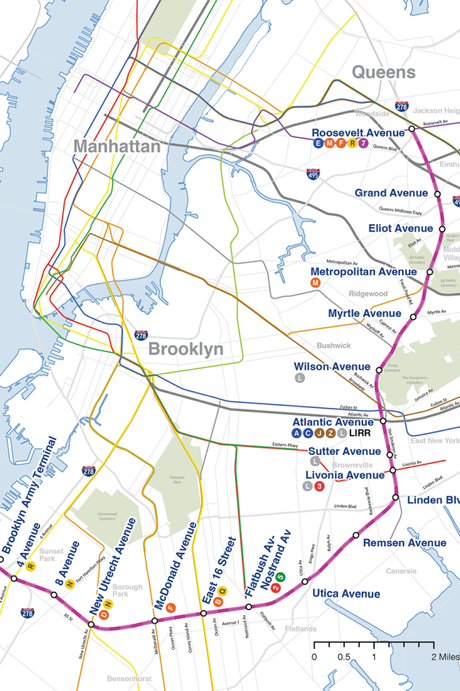

Governor Kathy Hochul later floated her own Brooklyn-to-Queens light-rail project, the Interborough Express, or IBX. With a route that hooks inland from Bay Ridge through eastern Brooklyn to Jackson Heights, it’s designed to run along an existing freight line rather than city streets, making it theoretically simpler and less disruptive to construct. The plan is different from the BQX, but the ambition is similar: bypass Manhattan and counter the subway system’s radial rigidity. That scheme isn’t dead; it’s just mired in the cogitation phase. While the MTA keeps nudging the project along, the prospects for both funding and federal approval remain cloudy.

The Interborough Express: a favored Hochul project that has been studied a lot and funded a little. MTA.

The Interborough Express: a favored Hochul project that has been studied a lot and funded a little. MTA.

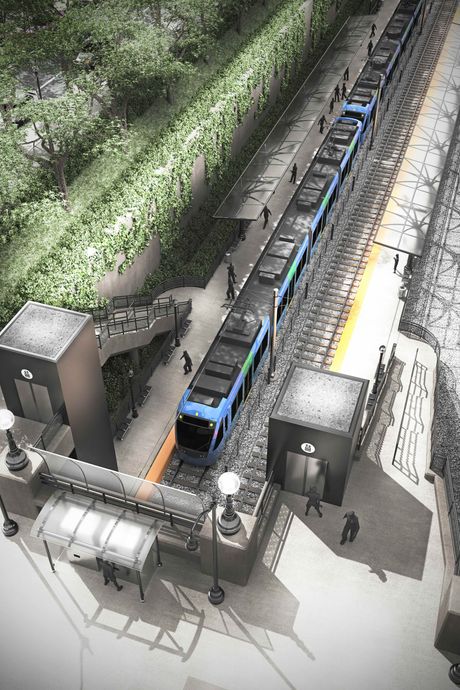

Then there’s Sunnyside Yard, a huge void in the heart of Queens that could have modeled the car-light city we need. In early 2015, the de Blasio administration started plotting to cover the 180-acre railyard with a deck, a new transit station, public spaces, and 12,000 apartments. The city commissioned a master plan from the firm Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, which envisioned a neighborhood six times bigger and infinitely more organic than that other Oz-on-a-plinth, Hudson Yards. PAU’s plan grew out of the assumed need for shared space — not the narrow esplanades with which developers are obliged to fit out new waterfront estates but a genuine network of private courtyards, wide sidewalks, narrow side streets, neighborhood parks, and plazas, linked by a central pedestrian artery. It was the rare plan that treated housing, open space, and public transit as a continuous flow and recognized that they all need to be mapped out together. The linchpin was a regional transit hub, Queens’s own mini Penn Station. LIRR, New Jersey Transit, and Amtrak already share the tracks below, and a new Sunnyside station would further the dream of the kind of integrated system that New Yorkers can only fantasize about. Imagine being able to transfer from the subway to Metro-North’s urban stops on a single fare or get on a train in Newark and get off at JFK.

None of these projects — the BQX, the IBX, or Sunnyside Yard — was ever going to offer the complete and final answer to New York’s needs, but each represents a vanishing form of optimism, the belief that the city can one day regain its vigor and be worthier of our stubborn love. For now it’s aging into a fatalistic dowager, meeting the future with a vaguely disapproving sigh. Getting the Sunnyside Yard project started, let alone finished, would require the seamless cooperation of the city, the MTA, Amtrak, the governor, and the federal government. It died, or at least fell into a cryogenic coma, not because it was unworkable, impractical, or impossibly expensive but because it was just too much trouble. Just think of the immense catalogue of stuff that we could have had if only our leaders had followed through.

The result of this lassitude is that cars still rule the streets. Despite decades of activism, a cultural shift among transportation professionals, the advent of congestion pricing, and endless bickering over bike lanes, most of New York’s public space doesn’t look terribly different from the way it did half a century ago. For decades, the city meekly adapted to whatever vehicles the world threw at it: 18-wheelers, juiced-up bikes, rocket-propelled scooters, testosterone pickups, swarming Ubers, Amazon box trucks, ATVs (not street-legal, but never mind), and SUVs capable of fording streams and climbing rock walls. That universal welcome relegates pedestrians to the status of unmotorized pests who keep getting in the way; if they frequently get menaced and occasionally maimed, that’s just the cost of doing business. The next mayor must understand that car supremacy cuts into public space, threatens public safety, and erodes the public’s quality of life — just ask the families of 121 pedestrians who were crushed to death by motor vehicles last year, mostly while trying to get from one curb to another. Society has proved willing to tolerate that level of heartbreak and gruesomeness, and it doesn’t need to.

The unbuilt Sunnyside Yard: six times the size of Hudson Yards with a huge transit hub and walkable streets.

Photo: Practice for Architecture & Urbanism

Renegotiating the city’s relationship with cars has the power to rejuvenate New York. In the 20th century, automobiles defined modernity. Gridlock represented an excess of urban energy. Today, private cars that go wherever, whenever, are signs of stagnation and retreat. A major metropolis that refuses to put them in their place — that doesn’t, for instance, nullify the driver’s sense of entitlement — is sliding into a ravine. Paris and London have invested billions in expanding their regional rail web, extending transit service, whittling down traffic, and shifting primacy to pedestrians. New Yorkers spend so much time ducking crises that get lobbed at them like Molotov cocktails that the need to prepare the post-automotive city feels less immediate. But it isn’t. A healthy city needs a healthy circulatory system, a varied one, in which people can get where they’re going by whatever means makes sense, depending on timing, weather, and cargo. That may mean an Uber at 2 a.m. or a private car for a trip to a specialist’s office. Mostly, though, it should mean a safe, reliable, and integrated network of buses, subways, regional trains, ferries, and bikes plus a congenial pedestrian landscape and unflooded parks.

If you read government press releases, you might be fooled into thinking that our leaders were making significant progress toward those goals. But announcements, renderings, and photo ops of dignitaries with shovels camouflage the deep-seated inertia and wishful thinking that permeates New York’s growth. Flushing Meadows–Corona Park gets cosmetic enhancements but remains a fragile flood zone. Penn Station breeds more and more plans to relieve the dismal odyssey of a cross-Hudson commute, but so far all we’ve gotten is a nicer Amtrak waiting room plus a billion-dollar duct-tape job that leaves the concourse looking fresher and does nothing to alleviate breakdowns and delays. The derelict Brooklyn Queens Expressway, which has been deemed too brittle to patch, too cumbersome to bury, and too crucial to dismantle, keeps getting handed off to the next administration. And several blocks of tunnel below Chinatown, dug half a century ago for the Second Avenue subway, remain a vacant, unseen taunt. Eric Adams campaigned on a promise to create another 300 miles of protected bike lanes by the end of this year. He’s got 211 to go. He also vowed to devote one percent of the budget to parks and delivered a little over half that. True, the Port Authority managed to squeeze a nearly $2 billion loan out of Joe Biden’s federal government to help with the $10 billion (and rising) cost of rebuilding its bus terminal. But if you think that means a new station is coming anytime soon, remember that the Feds wrote the first check for the Second Avenue subway in 1968. The first three (and, so far, only) new stations opened 49 years later. Even minor signs of progress have to bust through a default setting of self-defeat.

No mayoral administration has the power to tackle these challenges alone, or all at once, especially with a hostile president who claims he used to ride between subway cars but has never been observed inside one. Often, the city is its own worst enemy. Public agencies are filled with professionals who understand that it’s the people not driving who determine whether the city thrives. But each day, those staffers struggle to move their designated projects a few millimeters toward realization. They have public hearings to endure, environmental reviews to negotiate, City Council members to cultivate, Community Board members to placate, unions to negotiate with, antiquated hiring rules to follow, and so on. The result is a pervasive lack of urgency. Whatever should be done today can wait until next year, by which time rising costs and the fear of opposition will have muted the project’s aspirations. It takes immense and sustained effort plus a lot of political capital to overcome this procedural paralysis.

But a mayor can conjure an achievable vision, then doggedly chase it down, even if the rewards take longer to materialize than a four-year term or two. The future we should be working toward is not some techie fantasy of urban gondolas, Musk tunnels, and urban air mobility. And it won’t be achieved in increments alone, with a crosswalk here and a bollard there, or a minor improvement in the streetscape that gets fought over like a few feet of terrain at the Somme. Instead, the list of needs ranges from stripes of paint on asphalt that can be completed immediately to multibillion-dollar rail projects that should at least get started — now. It took decades to adapt the 19th-century city for 20th-century cars. That coordinated, multifarious campaign involved building roads, narrowing sidewalks, tearing down neighborhoods, codifying regulations, installing gas stations, wiring stoplights, repurposing curbs for parking, and erecting garages. You can’t undo or update all that by thinking small. A visionary New York would face the future with an equally robust to to-do list: Deck over the Cross-Bronx Expressway, bury the BQE, expand the subway network in the outer-boroughs and across the Hudson to New Jersey, multiply the number of station elevators, restore dilapidated parks, incorporate Metro-North stations into the urban transit system, carve out more genuine bus lanes, create new pedestrian boulevards, ramp up traffic enforcement, multiply the number of speed cameras, normalize speed bumps, cap e-bike speeds, bring rogue delivery riders under control, and build elevated bikeways. And that’s just for starters.

In 1972, we dug a few blocks of the Second Avenue Subway downtown, by the Manhattan Bridge. The tunnel’s still there; the trains aren’t.

Photo: New York Transit Museum

Transit, parks, and streets are the most visible, and the most vulnerable, indicators of urban health. Daily irritants in public space can quickly devolve into signs of a failing city. In the ’70s, photographers satisfied their cravings for seediness by enshrining graffiti, litter, and abandoned cars as the desperate icons of that time. Central Park was carpeted with dust, Bryant Park with needles, and together they represented an especially demoralizing form of surrender. In the ’80s, de-graffiti-fying and air conditioning the subways proclaimed to the world that New York was purring again. And then, on the far too frequent occasions that an LIRR train derails, a century-old swing-span bridge in New Jersey fails to swing, signal malfunctions throw the subways into disarray, or the 120-year-old Hudson River Rail tunnels fail, commuting once again starts to feel like an insane ordeal, and workers stop being willing to endure it. In Movement: New York’s Long War to Take Back Its Streets From the Car, Nicole Gelinas envisions two possible futures. “In one, New Yorkers, commuters, and visitors ride subways and buses in safety and confidence.” In the other, “subways and buses become the domain of people with few options,” those who can retreat to their private vehicles do so, and “nobody wants to walk, cycle, or dine outdoors, amid gridlock, noise, and danger.” The public realm, still the city’s most powerful and most democratic attractant, needs a dramatic overhaul, before the affluent confine themselves to the real estate they own and everything else comes to resemble the sidewalk in front of a vacant store after a snowstorm: unshoveled, unclean, uncared for.

But defeatism isn’t destiny. New York has a record of being bullish about the future and acting on that mood. When I try to imagine the city I hope to live in one day, I reach back — way back — to a time when it was bursting from its long preindustrial squalor into an electric feeling that modernity could be thrilling but also easeful and fun. In a silent-film clip shot in 1911, we see New Yorkers navigating a teeming ecosystem of transit. You can watch it here now (start at 6:25 to see the intersection shown above):

Horse-drawn omnibuses, cabs, and wagons share the pavement with electric trolleys and private automobiles. Crowds disembark from ferries and steamships. Elevated trains coexist with the new and growing subway system. Despite all that vehicular movement, it’s pedestrians who own the streets. You can see it in their body language. With no lanes, traffic signs, or stoplights, people amble diagonally from curb to curb, confident that traffic will avoid hitting them. (The gridded trajectories we follow today, with right-angled turns at streetcorners, came a few years later, a kind of pedestrian discipline imposed by cars.) That dance of crowds and machines embodied the spirit of the age. In those nine minutes of footage, the camera meanders through an optimistic, dynamic metropolis where new technologies breed new visions and big plans. We see skyscraper architecture being adapted for the next generation, the city reshaping itself around insurance, media, and banking, connecting itself ever more tightly to the rest of the world through shipping and rail. Manhattan merged with Brooklyn a dozen years before, and here is Greater New York, spreading into new suburbs, boroughs, and garden cities. Bridges are quickly knitting the whole agglomeration together — more than a dozen in just three years.

Walking, riding, limping, trudging, scooting, strolling — all the various forms of low-speed locomotion — define the experience of being in New York. The ability to move through the city with minimal misery is the basic apparatus of urban living. Without it, the invisible walls between neighborhoods grow higher and inequality spreads. Developers have few incentives to build in areas that are difficult to reach, which keeps the housing supply at a trickle. You can’t build more homes without more density, and you can’t build more density without more transit and fewer cars. When getting around is arduous and unsafe, workers rebel against their commutes, depressing the value of commercial buildings. People stay at home and shop online, ravaging the streetscape of storefronts. Gradually, New York loses its magnetic pull.

That culture of the commons, the ethos of shoe leather and chance encounters, still distinguishes New York from most American cities. But urban pedestrianism doesn’t just endure on its own. It needs to be nurtured, updated, democratized, and paid for. That’s where leadership matters. In the 1960s, Governor Nelson Rockefeller overhauled New York’s public-transit system and created the MTA. He also announced that Battery Park City would be built in what was then nothing but marshy shallows. Two decades later, it was a full-fledged neighborhood, leading the slow metamorphosis of the Financial District into a bedroom community for about 150,000 residents. Michael Bloomberg took office months after the 9/11 attacks, and, instead of governing in a defensive crouch, he and his whip-cracking deputy mayor Daniel Doctoroff drew up a citywide planning document with a to-do list of 127 specific items, ranging from medium to vast. By the end of Bloomberg’s mayoralty, his administration had knocked off nearly all of them — including the beginnings of a network of bicycle lanes and pedestrian plazas. (The major exception to that record of success was congestion pricing, which has finally arrived and might even be entrenched enough to withstand Trump’s desire to scrap it.)

Granted, this is not a great time to wax wistful about Republican plutocrats with high-handed manners and a conviction they were always right. We’ve already got two of them now, recklessly swinging their sledgehammers in Washington. There’s a crucial difference, though: Trump and Elon Musk are laying waste to a government they hold to be not just sluggish but evil; Rockefeller and Bloomberg came to office believing in government’s unique ability to accomplish big things in the public interest. It wasn’t wealth or party that allowed them to get things done; it was the conviction that a capable captain can nudge even the most becalmed vessel into motion. New York’s next mayor must be able to envision the humane city, then command the obsessional determination, managerial talent, and tenacity to build it.