Pop-up Bookstore Honors a Man Who Meant to Give It All Away

Recirculation, as Word Up volunteers call it, is a pop-up bookstore filled with books and music collections by Tom Burgess.

Photo: Veronica Liu

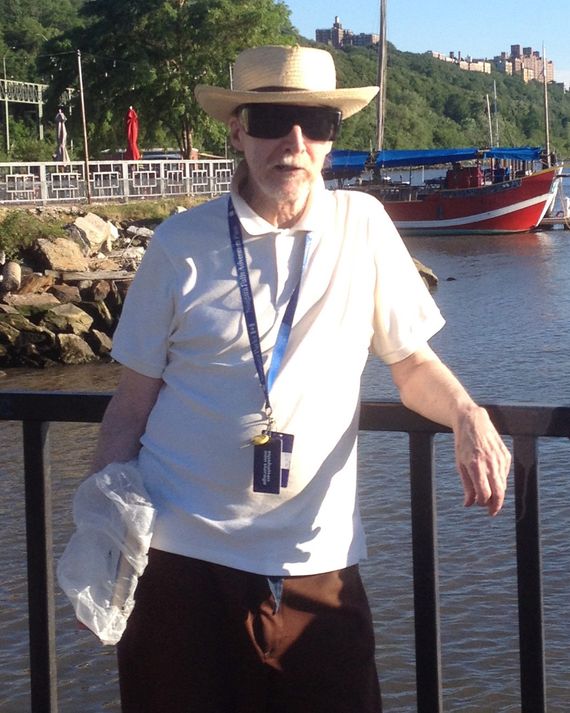

On April 21, 2020, in his New York-Presbyterian hospital room, 70-year-old Tom Burgess asked a nurse to turn up his oxygen so he could make one of the last phone calls of his life. Burgess had COVID-19 and was going to be put on a ventilator soon, but had to speak to a bookseller.

Veronica Liu, founder of the Word Up Community Library in Washington Heights, was the person he called that day. They had gotten to know each other after Burgess began volunteering at the store in 2011. Born in Michigan, Burgess was an archetypal New Yorker from the Voice of the village era: He moved here in 1975 and led a rich, albeit at times precarious, life. He had not married or started a family, and for years he was a member and sometimes an instructor at the Institute of Yoga. He had also been an assistant professor of anthropology at the city’s colleges and universities for decades and was active in union campaigns for the rights of auxiliary workers. In his later years, even after reaching retirement age, he continued to teach at the Borough of Manhattan Community College despite vision problems and leukemia treatment. He may have stopped earlier, his sister Barbara Hendrick told me, but he needed to teach a minimum number of classes to keep his health insurance.

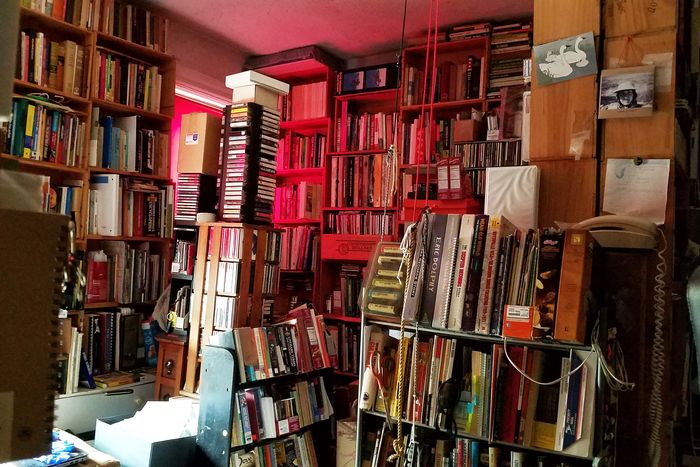

One thing Burgess was known for to those he knew – and what drew him before his last phone call to Liu – was the asteroid field that filled his orbit, his vast collection of books and music. For many years, Tom had felt compelled to collect novels, academic journals, travel guides, magazines, volumes of poetry, records, CDs, audio cassettes, VHS tapes, DVDs, comics, in addition to odds and ends like a board game, a trash can, a breadmaker, back issues of the Voice, anything that could one day be marginally interested in anyone. He lived by a philosophy he called “recirculation,” a process of collecting and reusing objects based on the idea that capitalism had already produced enough to circulate. So he went on with his life aspiring to be a matchmaker between readers and their perfect books, although more often than not he had trouble getting them to meet.

Burgess’ objects, tens of thousands of them, filled every cubic inch of space around him. He kept a cart of books outside his apartment door that the neighbors could choose from. And he used the bookstore, Liu recalls, as a pickup point for things he wanted to donate: “You would open a box, suddenly there would be a bunch of stuff that wasn’t at all to do with books. You waited a minute, then someone would come in and say, “Oh yeah, Tom left a bunch of coats for my dad.” It would still be tied to Tom.

Burgess’ apartment, crammed with books and tapes.

Photo: Veronica Liu

“I guess Tom would be offended to be called a hoarder, but I know that’s what people would say,” his sister told me. “You look towards [his apartment] and you should say that. But everything he had, or almost everything, I think he originally had because he intended to pass it on to the right person. Indeed, he didn’t just accumulate them – Burgess read many books he had collected and listened to many CDs (although a friend reported that his apartment did not have a record player for read one of the thousands of records at the time of death).

Those closest to him knew the things he was collecting had become a hindrance – boxes of books took up much of the floor space in his one-bedroom apartment, forcing anyone through the front door. to walk sideways and around a library to even reach the lobby. . He had reused dozens of wooden wine boxes as shelves, stacking them unsecured against the walls and filling them up to the ceilings with books. His kitchen was almost unusable; the oven could not be opened because of the batteries and there was a bookcase in the middle of the room. The living room was barely walkable, and Burgess’ bed was cradled on three sides by crates and shelves of his favorite books and CDs. Even then, the apartment was unable to hold everything, so it split into four storage units, the costs of which undermined her meager income.

Those who knew of Burgess’ life situation feared that the shelves he had fashioned would collapse on top of him or become a fire hazard. They also feared that the accumulation of his possessions would weigh on his psyche; for every object he gave, he took five more. There were also interpersonal conflicts. Disagreements arose at Word Up over Burgess’ habits because he was loath to throw away anything and tended to view imperfections – handwriting in an old math notebook, for example – as added value. , rather than a reason to throw away an item. A friend who had once offered lodging to Burgess was surprised to find that he had been given a mattress to sleep on that was lifted five feet off the floor by shelves and boxes. “I think about how in the cartoons when there’s, like, an angel on one shoulder and the devil on the other shoulder and they’re trying to help a person make a decision,” her told me. friend Gio Andollo. “Tom didn’t have this character in his psyche that was like, ‘Maybe we shouldn’t keep this. Eventually it got out of hand. “

For anthropologist Bernadette Bucher, a close friend and colleague of Burgess, her practice of preserving – exalting, really – the mundane, tattered, and obscure had a deeper meaning. French scholar Claude Lévi-Strauss once described anthropologists as the “ragpickers of history,” those who pick up what historians would throw in the trash, Bucher told me. Burgess was the anthropologist and ragpicker of her own life, she said. “You see people piling up unwanted stuff. And to the layman, this is all trash, things you throw in the trash. But the flip side in his case is that he preserved things that might go missing because everything is now digital.

During his last phone call to Liu in April, Burgess considered, for what may have been the first time, relinquishing some control over his oversized collection. The conversation, Liu told me, was partly a moment of calculation and partly a denial. “He said, ‘I tell you what, in case I’m ever sedated’ – he never said, ‘In case I don’t come out alive,'” Liu recalls. She agreed to take care of her business no matter what, and on June 3, Burgess died and his asteroids started crashing into Earth.

Tom Burgess.

Photo: Barbara Hendrick

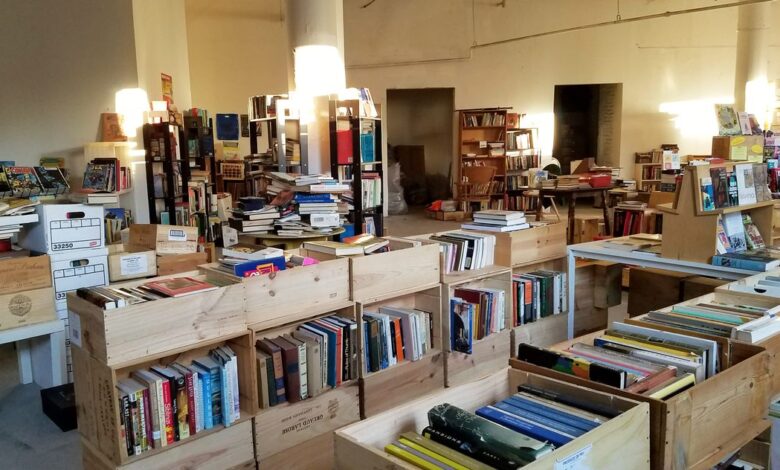

Over a period of several months, in an effort led by Liu and assisted by dozens of Word Up volunteers, Burgess’ collection was packed and moved from his Inwood apartment to the common area of a co-op building at 876 Riverside Drive. in Washington Heights. The space now functions as a pop-up store where Tom’s enormous collection is displayed in the way he would have intended if he had had more room and time. Post-its to friends in Burgess’s handwriting still hang on the covers of many books, and most things are still organized in its makeshift shelves. The store is open to the public on Sundays from 3 p.m. to 6 p.m. and Wednesday from 5 a.m. to 8 a.m.

The breadth of Burgess’ interests is evident in the collection: there are books on music, birds, Marxism, travel, poetry, racism, Latin American history, science fiction, and New York; there are past issues of academic journals, comics, Playbills and old photos. In one corner is his vast collection of jazz, rock, folk and pop records, including music from Buffy Sainte-Marie, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and Phil Ochs. “Inasmuch as someone’s possessions or whatever they’ve organized is a reflection of their mind, there was great beauty inside that skull,” Burgess’s friend told me, Sandy Jimenez.

In the spirit of recirculation – this is what volunteers have adopted to call space – most of Burgess’ collection is for sale on a pay-as-you-go basis. Liu tries to get the profits from the pop-up to go to Word Up and negotiates with the organization’s board to take over the project. (A few sections of the collection will stay together: a community center in Standing Rock, South Dakota has agreed to take the books on Native American culture, and the New Jersey radio station WFMU is set to take a few records. , just like the ARCHIVE of contemporary music in Manhattan.)

Jerise Fogel, a Word Up volunteer, said she was struck by the generosity of the community that takes care of the affairs of Burgess: “This is a very special and unique way to make sense of the world, a contribution to humanity. that she would never have been able to appreciate or accept if the friends of Tom’s Word Up had not engaged in this backbreaking and tedious work. And not everyone is so lucky, so much support. Without loving friends to understand and cherish you, your path can easily become non-existent when you stop. “