Brownstone Shared Housing:

Theoretically, you could live here.

Photo: Auseklis / Getty Images / iStockphoto

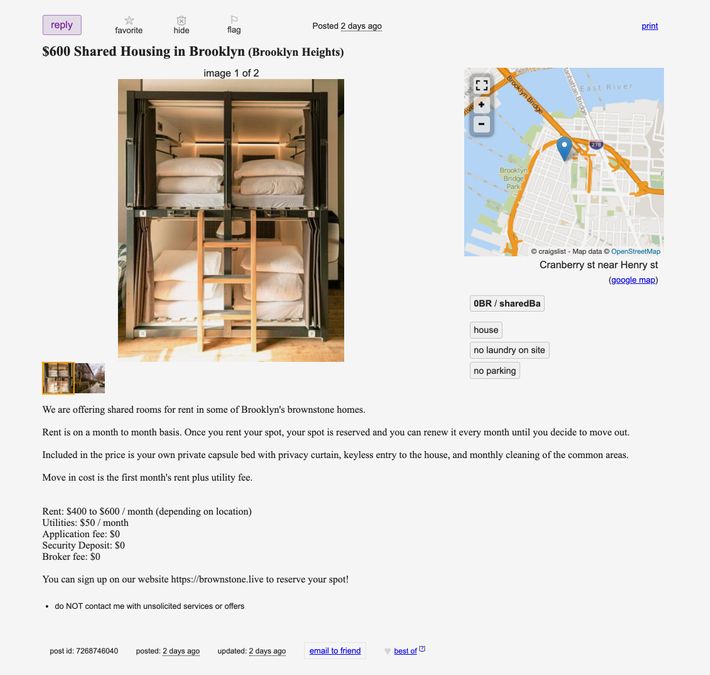

The hour is moving again, unfortunately. You would like to stay in Brooklyn, but above all the room should be affordable. A curious list nodded on the Craigslist apartment rental page: $ 600 per month in Brooklyn Heights? It turns out to be in the prettiest part of the neighborhood, near the intersection of Cranberry and Henry streets. The photo does not show anything that looks like a coin; instead, there is a large square structure divided into four lockers, each furnished with a thin mattress, a small bedside shelf, and a light source – they evoke extra-comfortable body drawers or a DIY version of capsule hotels in Japan.

The message directs you to a website that promises “early access to our addresses.” Sign up and you get a response presenting yourself as an urban forty-nine: “Heads up pioneer!” You ended up in a gold mine. We just sent you an email with more information about Brownstone. In fact, the precious ore is theirs, in the form of your newly harvested email address.

It turns out that even in the turbulent COVID economy, Stanford graduates have their startup ideas out of the box. Brownstone Shared Housing was founded by James Stallworth (Stanford ’17) and his romantic partner Christina Lennox, who met while working as state auditors. They live in Los Angeles, and Lennox already owns and rents a property in California, although Stallworth adds that he’s “a big fan of the New York area” and usually visits once or twice a year. (They removed the ads from Craigslist last week, moving the information to Brownstone website.)

Their big idea is to rent and convert single family brown stones into homes for up to 30 residents. Each room would be equipped with one to four two-person “pods” – or two to eight people per room, depending on the square footage. Rent would be between $ 400 and $ 600 per person per month, plus utilities. Brownstones would become, for lack of a better term, high-end flophouses, or perhaps permanent residence youth hostels. And for their efforts, Stallworth and Lennox could earn up to $ 18,000 per month in income per building.

They say they’re not just there for the money, however. Stallworth says he wants to help people who must arrears rent due to the pandemic crisis – and landlords who owe that rent – by serving as a WeWork-like intermediary for apartments. He plans to pay landlords more than the market rate to rent their buildings, in part to “encourage them to take the extra risk of having so many people in their homes.” In the meantime, it will put so many residents in each house that their overall rent payments would be much higher than what the apartments would normally earn. Then Brownstone would take its share.

The announcement.

Photo: Craigslist

Stallworth frames his idea in the murky utopian language of many tech companies. “If we want to get there, the future is shared,” he addresses his pioneers. “It takes a little courage to say, ‘I’m going to step into the future and I’m going to share my living space.’”

Judging by the description and this photo, this whole plan is likely illegal under New York rule as well. Single room occupancy laws, unless the brownstones in question are considered ORS hotels. Most zoning in New York City limits rooms to two adults, and the city Housing maintenance code requires that they be at least 80 square feet, have a window, and a minimum width and height of eight feet. When asked, Stallworth isn’t worried about any of this, as he believes Brownstones built before 1929 are exempt from such requirements. “We have reasonably eliminated that,” he says. “This is one of the reasons we’re not embarking on a new midtown Manhattan skyscraper.”

“This thing is clearly wrong,” says Edward Josephson, director of housing and litigation at Legal Services NYC, though he is quick to add a warning from a lawyer that legal boundaries can be delicate. “You are not allowed to create illegal rooming houses. Buildings are not supposed to be rented in violation of their occupancy certificate or their I-card. He says creating several new apartments on a floor that previously contained only one would require obtaining a new occupancy certificate. Many neighborhoods also limit the number of families allowed per building, he says, and Brownstone could break those rules as well. “He’s likely to violate, like, 93 different things, and they’ll come out on the wrong side of at least one of them.”

“The claim that all buildings constructed before April 18, 1929 are exempt from occupancy standards is false,” adds Matthew Main, CUNY instructor and low-rental housing advocate. “Based on [Stallworth’s] Logically, “almost all brown stones” would be exempt from the laws that govern the legal occupancy standards in New York City. This is simply not the case. The section of the law that Stallworth quotes actually says otherwise, saying the two-adult limit applies “regardless of when the building was constructed,” according to Main. And the regulations of the Multiple Housing Act apply to older buildings if they are altered or converted after 1929. The main offerings that Brownstone’s proposal reminds him of are three-quarters of the houses that house people recently released from prisons, prisons, drug rehab centers, hospitals and shelters. They cram eight people into a room, at $ 215 per bunk per month, the amount covered by public aid. They often violate occupancy standards, adds Main – although he also believes those standards should be relaxed, given that roaming is often the alternative.

Faced with these potential legal difficulties, Stallworth doubled down on its affordability promise, although it’s unclear how its business calculations would work: “If we were limited to two people in each room, our price of $ 400 to $ 600 would not be. not affected, as our primary commitment is to provide low-rental housing. As for the rest of the city rules, “our understanding was different when it came to occupancy standards. We will have to adapt to make sure that any contracts we sign comply with the law. “

Main and Josephson also suggest that Brownstone rentals would likely qualify for rent stabilization, which applies whether the apartments are legal or not. For example, Josephson points to a New York state decision from 1997, who found that the tiny “cabins” of a Bowery flophouse, rented by the night, were subject to rent stabilization protections. These offer protection against eviction without cause, rent increase regulations and a continuing right to one or two year leases.

Brownstone Shared Housing home page. It’s brown.

Photo: Brownstone

But back to Stallworth. He explains that when he couldn’t get into college accommodation towards the end of his time at Stanford, he fought for free accommodation when he learned to be the basement manager of a shared house. in Palo Alto for a man who rented a bunk bed for $ 1,000 a month. “I thought I could do something better than that,” Stallworth says. He and Lennox are designing a multi-city stronghold, but for now their focus is on Brooklyn, in the neighborhoods near Prospect Park. Currently, however, their brown stones are mostly imaginary. The Brooklyn Heights location listed on Craigslist is ambitious and approximate. “We’re still working on landlord agreements, so no properties yet,” Stallworth says.

And indeed, the four-section room appearing in the ad doesn’t exist – or, at least, not in Brooklyn. A reverse image search reveals the photo is borrowed from an Airbnb page to CoDE Pod-The CoURT Hostel, a converted Victorian courthouse and prison in Edinburgh. Stallworth promises that the Brownstone pods will be slightly larger, with a built-in fan and different lighting. He also says the capsule beds he will use will be different from the ones he’s seen in the United States, which he sees as colorful and high-tech novelties.

Yes, Brownstone’s capsules are inspired by Japanese capsule hotels – two six-foot-three friends from Stallworth had a “really cozy” evening in such slots, he says. But a more fundamental influence, he says, is an episode of Master of None, titled “New York, I love you,” which follows a taxi driver sleeping in a bunk bed in an apartment shared with several other men. (The episode involves a fictional movie with the tagline, “Everyone’s dying to go out.”)

Admit I signed up before I knew exactly what was going on. An informational email from Brownstone appeared in my inbox with the warning that the company is “testing our product in beta.” Stallworth told me he was “starting to understand product / market fit”, employing a term popularized by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen that seems to mean “exists and has loyal customers”. However, Brownstone has yet to find support. So what early access did we get to our pioneers for the price of our email addresses? At launch, we will have priority for a cubby. Stallworth compares this list to Ticketmaster. “One of the reasons it’s important for people to sign up and show that they’re interested is, of course, that investors don’t need a roommate,” he says. So far, they have collected around 300 email addresses.