Davis Center Opens in Central Park’s Harlem Meer

In the 1960s, a concrete skating rink combo was plunged into the northwest corner of Central Park. Taked halfway in a turn in Park Drive, muscling on the Harlem Meer and stifling a stream which was making a path on the west side, the structure did not sit as much in its site as the squash. If you have approached it by departing through the curved trails of the Woods North and through a picturesque stone arc under the reader, you found yourself faced with what looked like a suburban supermarket: concrete wall, garbage dumplin, garbage cans and a range of buzzing coolers. None of this, however, he had to go. Robust civic burn can bear indefinitely as long as it continues to operate, but the Lasker skating rink and swimming pool were a fled, and the Central Park Conservancy saw that it could transform decrepitude into opportunity by replacing everything and finding ways to give East Harlem neighbors.

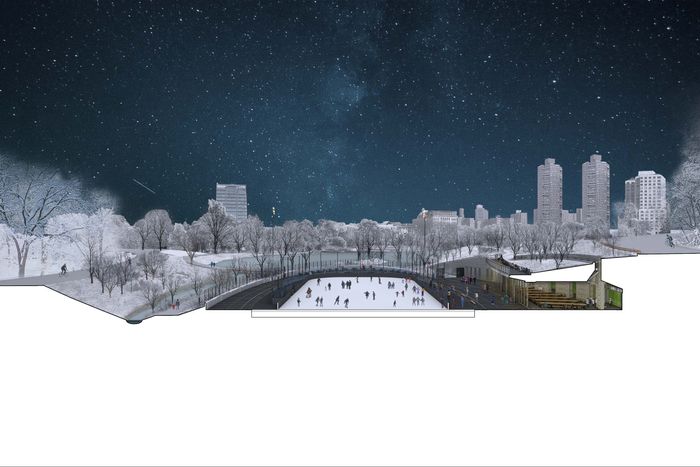

The result is the newly open Davis Center, by Susan T. Rodriguez Architecture and Design with Mitchell Giurgola Architects, which defeats the clumsy intrusion of Lasker and slides a large machine for leisure in an ovoid buffer area between the hill and the restored waterway. Navable tracks in wheelchair now mix in the perimeter, through the roof, and even through the structure itself, connecting to a new walk that bypasses the Meer. The flow flows again along a new bed between strategically positioned rocks. The new center returns more parks in the park. And the jewelry seated on a green cushion is a new swimming pool that turns into an ice rink in winter and an artificial lawn in the shoulder months, flanked by a public building that grows in the hill.

The new building contrasts in the hill, its roof covered with greenery above and ribbed with Douglas tree slats below. Photo: Richard Barnes.

The new building contrasts in the hill, its roof covered with greenery above and ribbed with Douglas tree slats below. Photo: Richard Barnes.

The Davis Center completes the efforts of several decades of Conservancy to transform the northern section of Central Park, once the most besieged and neglected area of the park, in one of the most attractive. The paths take place through woods filled with birds, passing by leftover restored from fortifications of the war of 1812. The ravine offers cool and shadow even the most blister. And although tourists discovered the charms of the region, the conservancy horticulturalists have made a valiant battle with other invasive species. The Meer and Rink trains the front door of East Harlem, and the new layout replaces insidious dead ends with an attraction of $ 160 million-and, boy, he will attract. Instead of turning it to a private company (such as the Trump organization, for example), the Conservancy will manage the installations itself, keeping access to the free pool, modest skating costs and the hours of zes filled with low-cost events. (The swimming pool is now Olympic but narrower and 25% smaller than it was, a concession with more recent code and accessibility conditions.)

Recreational water and well -managed ice would make people happy even if they were not accommodated in anything more glamorous than a large bathtub. And yet, it is also important that the new center site is formed by graciously crossed curves: the Swedy S in the reader, the edge of the Meer, the sweet turn of the tracks, the contours that was torlled from the topography. Rodriguez negotiates these lines with two arc movements: the oval of the swimming pool, flanked by a building in the shape of a scimoter which curves in the other direction. This large room is filled with wooden tables, one side lined with Adirondack granite, recalling the rustic stone in the rest of the park, the other a range of chorus glass doors that rotate outside. A roof covered with greenery above and ribbed with Douglas fir slats under sales on a row of thin columns and black cruciforms that come to a dagger cone at each end. A long sharp skylight, like the glow on the edge of a blade, leaves the sun’s course on the stone wall.

Rendered from the site as it looks in summer (swimming pool) and winter (skating rink). Photos: Susan T. Rodriguez.

Rendered from the site as it looks in summer (swimming pool) and winter (skating rink). Photos: Susan T. Rodriguez.

These few large gestures are equipped with an abundance of sensitive details, such as flared doors that seem more generous than they are, tiles of corridor frozen in the green, narrow strips of accentuation stone which slightly exceeds the shallow shelves, and a strip of diffuse frosted locking (but not feeks) in locker rooms. On the inside and outside are braided together: the roof extends in a large canopy, and the inner stone wall turns and slides through the glass to become an exterior facade. There is a good obsession at stake here, the desire to count each square thumb. We can only hope that the same meticle extends to mechanical systems buried at sight under the plantations.

The scene of the site’s opening weekend. Photos: Patricia Burmicky.

The scene of the site’s opening weekend. Photos: Patricia Burmicky.

The site is the kind that most manufacturers prefer to avoid: too difficult to access, too many slopes, too much water, not enough space to maneuver. These drawbacks must have energized the designers, including Christopher Nolan, who spent three decades as the main landscape architect of conservation and continues as a consultant. It is not only that they slipped the building into a slope, supporting it against the retaining wall of the East Drive, or that they framed it with a green roof. It is because they melted architecture and the landscape to produce a poetic hybrid. The semi -understanding building is not really a New York thing – or a city – (except perhaps for the Irish Hunger Memorial, a low box which carries a piece of rocky countryside on its shoulder). But there are enough previous ones for an approach that you could call Hobbitre. An hour’s drive, in New Canaan, Connecticut, Philip Johnson put his Private paint gallery Under a mound and close it behind a steel door. On the Danish coast, big decided a local dunes museumCreating canals that converge in a casting square. A few tens of meters away, you could completely miss the place. And in Japan, Tadao Ando has spent decades cutting hills Naoshima Island And inserting the concrete rooms of a museum in the earth.

Unlike all these examples, however, the Davis Center feels open and ventilated – more like the Bethesda terrace of the Park, which negotiates the drop of the shopping center at the lake near the 72nd street with stairs that flank an arcade. Here, similar conditions produce a completely different effect. Instead of having a series of formal elements – shopping center, staircases, columns, fountain, lake edge – the architects have reshaped the whole area so that the clever desert of the ravine spills through the arc de Pierre d’Olmsted, the building camouflages in greenery, and nature flows to the fence of the swimming pool.

The rivers and the landscape restored around the leisure center. Justin Davidson.

The rivers and the landscape restored around the leisure center. Justin Davidson.

The Davis Center will have to continue to hum all year, absorb shocks from hockey teams and inexpensive skaters, the flow of children in summer in summer, and a constant flow of picnickers, bathers, concerts and yoga enthusiasts in the shoulder months. Each of these constituencies has its own rhythms and desires; Everyone exerts another type of pressure on a building which must resist everything calmly, effectively, constantly. In the end, architecture will be judged by the way people use it and the way it holds – that it always seems lively in six months or six. In the meantime, crowds have braved erratic times for a festive opening weekend, and even early on Monday morning, the neighbors had already started to converge, attracted by the new lawn, the tender trees and the open place which makes this corner of 165 years again fresh and young.

The view from above.

Photo: Earthcam