How Delivery Workers Won Their First Charging Hub

A rendering for a proposed parking pole for delivery people.

Photo: Courtesy of FANTASTICA

The idea came to Gustavo Ajche during the pandemic. As a food delivery man, the virus had not only forced him to keep working when it was dangerous, but also took away the few spaces where he could shelter from the elements and take a break, such as the atrium at 60 Wall Street, long a favorite haunt for him and other delivery people. One morning in late 2020, Ajche was walking down 86th Street with Worker’s Justice Project manager Ligia Guallpa when they passed an abandoned newsstand. He wondered aloud if they could be reused as shelters for delivery people. But Guallpa was doubtful; Ajche recalls her saying, “With the park department, it’s not that easy to get space from them, so don’t think about it.”

But on Monday, officials announced New York City would receive a $1 million federal grant to begin converting vacant newsstands into centers for delivery people. For Ajche, who was present at the press announcement, the most exciting thing was not to be alongside Mayor Eric Adams or Senator Chuck Schumer, who had joined the delivery men for a high profile bike ride a year ago and promised to secure funding for the hubs. It was the presence of Sue Donoghue, the commissioner of the Department of Parks. “She was there, standing with us. It makes me think that nothing is impossible,” he said.

This vacant Town Hall newsstand will be the first to be adapted to be a charging hub.

Photo: Courtesy of FANTASTICA

It was another victory for Los Deliveristas Unidos, a WJP-backed delivery collective that Ajche founded in 2020. In its brief existence, it has already won major political victories, such as the major reform package of the delivery industry they pushed through the City Council, which included a minimum base wage and a right to use restaurant bathrooms. Creating delivery hubs had become a major goal for the group from the start.

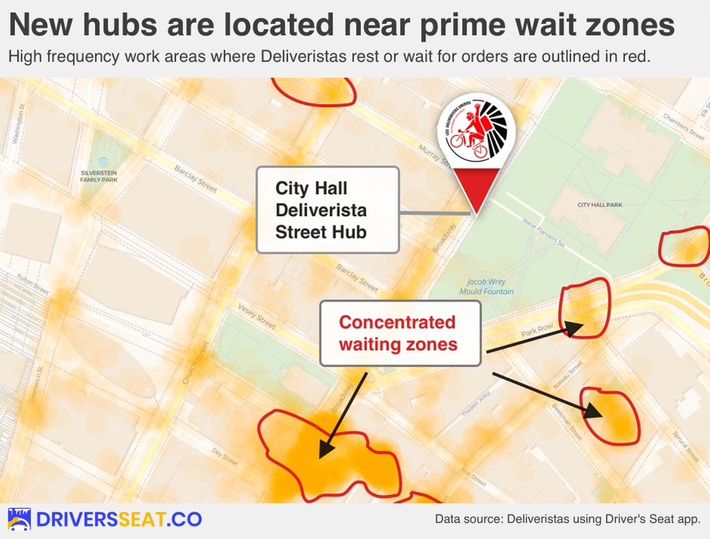

The first center will repurpose a large newsstand in front of City Hall and begin to take shape in the coming months, said Hildalyn Colón Hernández, policy director for Deliveristas Unidos. While the precise details of the hubs are still being worked out, the one adjacent to City Hall will be designed to provide shelter for workers to protect themselves from rain and snow and to charge their bikes and phones. Colón Hernández told me that the workers chose the site by aggregating the data they collected on Driver’s seat, a worker-owned and worker-focused app that allows workers to track their movements throughout their day. The app revealed hotspots near City Hall where delivery people spend a lot of time waiting, and the data will also be used to choose upcoming sites, she said.

Photo: United Deliverers/DriversSeat.co

Colón Hernández said workers originally proposed using parking spaces to build a series of low-cost, removable worker centers next to restaurants. But when they shared the plan in a meeting with Schumer and city officials over the summer, it was the city that suggested the concessions. “We were like, ‘Oh, that makes sense,'” Colón Hernández said. There are around 400 of these structures across the city, with obvious advantages: they are located in high traffic areas, have an established permit system and, perhaps most importantly, are already connected to the electricity. This should ease the burden on workers’ private residences, where battery fires have increased, leading NYCHA to propose a total ban on e-bikes.

Parking centers are still on the table, although no deal has yet been reached for them. But drafts of these designs give us our first glimpse of how they could change the streets of New York. In a rendering by designer J. Manuel Mansylla of fantastic brooklyn, the hubs appear simple and utilitarian. They have bar-height wooden counters and a small bench set up directly above three jersey barriers arranged in the shape of the letter “C”, surrounding a wooden platform that opens to the sidewalk. Two metal bike racks are attached to the exterior of the structure, which is topped with a roof that could include a solar panel to provide power for charging e-bikes and phones.

Mansylla told me the parking sheds would give workers a place to recharge their gear while waiting for orders, an idea he started thinking about in 2021 when he was commissioned to design an outdoor dining shed for Daily Provisions (he now works for Los Deliveristas voluntarily). The logic behind their placement on the street is to ease tensions between delivery people waiting for orders, customers and pedestrians jostling for space in front of New York’s busiest restaurants. Mansylla also thinks these parking shelters shouldn’t be just for delivery people, but shared with the public – anyone could rest and recharge there. It would be a way to capitalize on one of the key urban design lessons of the pandemic: that “the city didn’t collapse by allowing more parklets to live on the streets,” he said. . Mansylla thinks these shelters would serve a bigger purpose than the outdoor dining sheds, which only benefit restaurant patrons (“that’s why everyone hates them”). Of course, they would probably bother residents who just want free parking space for their cars.

But there’s one thing that’s conspicuously missing from both the newsstand and the parking lots: bathrooms. It’s a limitation workers have been forced to accept for now, as many of the city’s newsstands are simply too small, Ajche said. The problem is somewhat mitigated by delivery bills passed in 2021, which require restaurants to let workers use their bathrooms. But not all restaurants have complied, and it’s an issue “that we have to keep fighting for,” said Colón Hernández.

A partial solution will be the expansion of the Williamsburg Workers’ Center of the Worker’s Justice Project, which will be funded with remaining federal grant money, based on the number of centers built. The hope is to triple the size of the center to 3,000 square feet, said Colón Hernández. In addition to more bathrooms, the renovated space will include a training center and event space, as the group continues to grow.

Ajche said that as more people become gig workers, the need for supporting infrastructure has become apparent. “It’s really, really crazy. These apps are hiring more workers every day. There are places where a year ago you would never see a person standing with a bike or waiting for delivery. Now you will see small groups in different areas. That’s why he thinks the first hub can’t come soon enough – and hopes that many more will follow. That of course depends on whether or not more funding comes in, although nothing has been announced so far. “It’s something that needs to come into the city,” he said. “We’re going to be here for a while.”

See everything