Inside the Peter Thiel–Backed Praxis

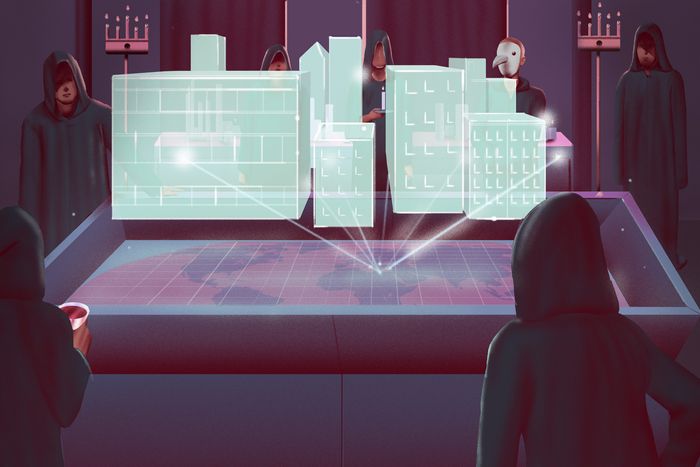

Illustration: Richard A. Luck

There is a long queue at the entrance to the Praxis loft. The process of simply entering the space delays things: we are asked to provide our names, emails, and a reference from a member of the Praxis Society; take a selfie with an iPad; and sign an NDA. When it’s my turn, I ask the woman guiding people if I can have a copy to review. The event organizer is called and seems troubled by the situation, so I can sneak out without signing the agreement.

The lavish loft is on the top floor of a cast-iron building in Soho with large latched windows that overlook Lafayette Street. It is both an office and a meeting space, with bedrooms on the upper and lower floors, where Praxis staff members live and work. The architecture of the loft is made more spectacular by the fact that it is lit by candlelight. A tune from the 18th century is played. Guests choose a surprisingly deli-quality platter of raw vegetables and chat before the show begins. No one in the room looks over 30. I join my friends Auri, assistant to the collections in an artists’ foundation, and Myles, freelance writer, chatting with a finance guy who looks like every other finance guy there. When the group has expanded a bit with some Wall Street guys and a few fashion boys, we’re introduced to the center of the room by Eric Wollberg, Praxis’ “community leader.” He entrusts her to Dryden Brown, the co-founder of Praxis, who is in his twenties and wears a black hoodie with the hood pulled over his head.

“We are building a city,” he says. “We are building a city from scratch. Somewhere in the Mediterranean.

The founders of Praxis – Brown, a graduate of NYU, and Charlie Callinan, who was a catcher for the Boston College football team – met in 2016 while working as investment analysts at Pleasant Lake Partners. On Jake’s pod, Brown recounts the time he and Callinan first discussed rethinking how cities are traditionally structured while surfing in Puerto Rico. “We just started talking about this crazy city stuff when we were sitting around waiting for the waves,” he said. This conversation was the start of Bluebook Cities, a company they co-founded in 2019 that aims to develop “affinity cities” based on a system of shared values.

Bluebook Cities’ first project is Praxis, which defines itself as “a grassroots movement of modern pioneers building a new city.“Put simply, the society aims to create a community of members who will live in a self-governing charter state built on a decentralized crypto-economy “somewhere in the Mediterranean,” as Brown often repeats. The foundation of the city of Praxis will be a shared set of spiritual principles: physical health, an appreciation of beauty and, above all, “the intangible attraction of the frontier”. No one will say exactly where in the Mediterranean this city will go. If we have to understand something former special economic zones built on crypto, one would assume that the host country chosen by Praxis has a low GDP and therefore stands to gain from leasing its land to a society of the richest and most powerful people in the world, while being stable enough to avoid the risk of regime change. I guess it’s somewhere in the Balkans, but of course that’s pure speculation.

Praxis’ digital footprint is small and cryptic. In December 2020, Dryden released a short test diagnosing the follies of contemporary urban life, arguing that cities are nothing more than labor markets devoid of common values. A little after, he announced Praxis’ intention to actually build a new city, with planning done entirely in the cloud. “Building a new city from the ground up is an opportunity for a radical reflection on first principles,” he wrote. “Modern transportation. Modular construction. Innovative governance. Decentralized currency. Default healthy food, default exercise in nature, default human interaction, and default property. … We’re building the city that Silicon Valley deserves. In early 2022, six permanent staff were living in the Praxis loft on the company’s payroll with investors including Peter Thiel and the Winklevoss twins.

Praxis is technically based in New York, but the team spends time actively recruiting from Los Angeles, the Bay Area, Miami and beyond, encouraging people to become “members”. Not officially employed, Praxis members volunteer to help develop the city alongside experts in “fields” such as governance, health, education, environment, security and commerce as well as culture and philosophy – the idea being that they create an infrastructure for the future city. “Web3 and the Metaverse are nothing without a vital and vibrant real world,” a Praxis member wrote on the group’s Discord. “That’s why I’m moving to Praxis.” Another: “We have more advanced technology than ever, and yet our society is in decline. Reshaping society requires more than rational arguments: it starts with culture. Praxis understands this. Culture, then cities, then society. We are defining a new identity for the next generation and bringing them together in the Galt’s Gulch of the information age. See you there.” To recruit these members, and to spread the word in general, Praxis employees are dispatched to tour Coachella and Cannes – and to organize events like tonight’s, which are meant to evoke the salon culture of the Parisian Enlightenment, Dryden tells us. The only subject we are asked to avoid is politics (although one cannot help but consider the group’s clearly libertarian leanings and the fact that Peter Thiel, the New Right financier, is funding much of this operation.) Politics, he says, is “eroding the conversation.”

In the loft, Wollberg divides us into three groups: “one”, “two” and “three”. I am seated with these and seated at a long dining room table with seven men and one woman: Myles and Auri, two nondescript finance guys, two cartoonishly handsome veterans named Rob and Daniel who served together in Navy Special Warfare Command, Paul Bandera of Praxis Strategic Operations, and Wollberg himself. Once installed, one of the financiers opens the conversation by wondering if a project like Praxis is born of necessity or of excess. He asks the group if we think the Praxis community is building this “eternal city” because they are fleeing an antagonistic environment or simply because they can afford it. Wollberg responds by asking if we are familiar with the concept of Janusian thought. Were not. He explains: Janus, the Roman god with two heads looking in opposite directions, symbolizes transition, the ability to simultaneously hold two conflicting ideas in one’s mind. One of Praxis’ goals is to bring together the best of humanity through “shared principles,” says Wollberg. Myles intervenes. “I’m super new to this,” he says. “So you are trying to build a new city. What would you do about something like crime? “You would have a monopoly of violenceWollberg answers in a neutral tone. He turns to Bandera, on his left, and asks: “Is the ‘monopoly of violence’ Machiavelli? Racking his brains, he replies: “It comes from Leviathan – it’s Hobbes!

From there, the conversation winds between Alexis de Tocqueville and the Founding Fathers, but things are constantly derailed by more practical questions from the group about establishing the city. Will Praxis have schools? Will it have a constitution? Wollberg is obviously frustrated with the interruptions. After comparing Praxis to the formation of Israel, I ask him if the land they intend to build on will have to be depopulated, to which he replies, “I worked for the government of Israel, so I really not going to go there. to get into this conversation,” then assures us that they only look at Greenfield sites.

The conversation more or less turned into a press conference, and Wollberg started making excuses for why he can’t answer much. He is “not free to”, he is “not the spokesperson” (although the identity of this spokesperson is not entirely clear), “this has never been the intention of this fair”. More, Bandera steps in, if we knew how far they’ve come so far, we wouldn’t be skeptical.

Before the night is over, I ask everyone at my table what appealed to them about this seemingly imaginary free society. Responses range from hating the two-party system (Democrats and Republicans are secretly in cahoots, that’s a catch), “intellectually controlled environments where dissent is not possible”, and recently almost walking in human shit walking down the street.

A week later, Auri mentions to Bandera that she would like to bring more friends to the next show only to find that the attendee verification system has been adjusted – it is now strictly invitation only with the requirement that potential attendees provide their LinkedIns and political leanings (“too progressive” person) for approval. Soon after, Bandera informs Myles that he is banned from the shows for asking too many questions. I’m banned too, apparently because I “didn’t sign the fucking NDA”.