Review of Waterline Square at Riverside South

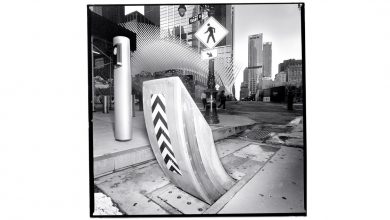

Waterline Square, on the southwest corner of the Upper West Side.

Photo: Elizabeth Felicella

On one of those hot, thick summer days that the brain goes into sleep mode, I gratefully rush into Harry’s Table, the Cipriani-branded Italian snack and deli in Waterline Square. As I browse through the display of three-inch-thick steaks and the display case of pies and meringues, I realize that I am witnessing the conclusion of one of the biggest, longest and longest real estate sagas. hotly contested of the last half century. It’s a sprawling series spanning multiple seasons with an array of characters ranging from neighborhood nudniks to future president. The tallest tower in the world! A wobbly highway! Muscular mayors! Debt Pits! A new city named after – you guessed it – Trump! The tale was told as a prequel to the MAGA Administration, a chronicle of chaos, inconvenience and fallacious claims to victory. But you can also see it, less operatively, as a slow lesson in disappointment, the triumph of low expectations and the danger of good intentions.

Back outside is a manicured lawn surrounded by a trio of jagged, excitable glass towers. Time has sorted the population. I’m sitting at a cafe table in the shade, with a handful of sturdy adults. The crowd of under-12s rushes through the hyperactive jets of a fountain embedded in the cobblestones. No one ventures into the playground that smolders in the afternoon sun.

Waterline Square is the final piece of the puzzle in the 57-acre site above the Hudson River that slowly grew south from West 72nd Street to West 59th Street, covering what was once an impassable strip of railroad tracks . Developers salivated over the area from the early 1960s and launched an assortment of doomed schemes. In 1981, a specially formed joint venture called Lincoln West bought the site with a vision of huge, tightly packed towers that a community board member memorably dismissed as “Miami Beach Maginot Line.” Then Donald Trump intervened, with a typically grand plan to move NBC into a 1,670-foot skyscraper at the west end of West 61st Street, designed by Helmut Jahn, as well as 5,700 apartments in a bank of big towers.

Trump has encountered two types of enemies. The first was neighbors who objected to a hyper-mega downtown offshoot popping up outside their living room windows. The developer eventually co-opted its opponents, having them sign a master plan that called for a swooping skyline of twin-towered buildings modeled after the palaces of Central Park West. The second confrontation was with Congressman Jerrold Nadler, whose attempt to damage the project by denying federal funds backfired: he managed to kill off a good plan to place the West Side Highway elevated against the cliff and cover it with a park. (He returned to Trump almost 30 years later when he served as director of the second impeachment.) The highway stayed where it was, saving Trump millions and turning the development into a billboard in roadside for himself. Now, he says, “when the cars pass by, they will look at our masterpiece.”

This statement turned out to be correct, except for the last word. Despite all the dire predictions, the plan got better and worse. But once construction began in the mid-1990s and Trump handed over ownership, it soon became clear that the design guidelines were too vague to prevent blandification. 87-year-old Philip Johnson signed on to co-write the type of architecture that mattered least to him, the set-back, Art Deco and decidedly bourgeois residential building. In the end, it was Trump mercenary Costas Kondylis who ensured the lineup would consist of one wide-bodied, square-headed, value-added tower after another.

In 2010, there was still a piece of undeveloped land left: a two-block stretch just north of West 59th Street, which real estate firm Extell and city planning chief Amanda Burden were determined to turn into a showcase. With Burden’s approval, Extell hired Pritzker Prize-winning Christian de Portzamparc (the architect of the elegant prismatic LVMH tower on East 57th Street and the super-large one57 horribly glitzy), who imagined a cluster of quartz-like glass towers bowing, splitting, and protruding in the finest deconstructionist fashion. Once the city approved the project, it changed hands again. This time, however, the design principles have been meticulously integrated into the zoning rules. The new developer, GID, brought in three separate high-profile firms – Richard Meier Associates, Rafael Viñoly Architects and Kohn Pedersen Fox – to execute the de Portzamparc concept. Now that the exquisite corpse of a project is also complete, the result is graceless but surprisingly satisfying.

New York has some notable examples of roughly homogeneous, planned campuses with individual buildings designed by disparate architects: the UN, Lincoln Center, World Trade Center, and Hudson Yards come to mind. What is rarer is that the vision of an author imposes itself with such fine detail on other architects of a radically different sensibility. Waterline Square brings together architects best known for Cartesian regularity Where bulbous monoliths (Vinoly), white parched modernism (Meier), and corporate skyline branding (KPF). The result is a set of dutiful attempts at weirdness, a collage of late deconstructivism by companies that never fully embraced the style.

All of this architecture serves to present Waterline Square as the anti-Riverside South: aggressive, fragmented and crystalline where Kondylis’ parade is heavy, predictable and poised. But perhaps the aesthetic appearance of the buildings is what matters the least. For residents, the real premium heart of the development (besides the river view) is the Waterline Club, an oversized underground anthill in which to spend their leisure hours.

It used to be that even restless aristocrats with their own swimming pools, pool tables and ballrooms still had to leave their gilded premises to play an all-court basketball game, go light mountaineering, record an album, play doubles, take the dog out, dine out, go bowling or practice a fakie rock on a half pipe. Here, everything happens below the street in a leisure complex that joins the three apartment buildings. If you live in one (and pay an extra membership fee), you can access this wondrous world via a suspended bridge-ramp-stair combo that seems to levitate in double-height space like an architectural hologram. Trust Rockwell Associates to turn a short trip to the treadmill into a gala-worthy entrance.

Among the underground facilities of the Waterline Club. Eva Joseph.

Among the underground facilities of the Waterline Club. Eva Joseph.

The roof of the club doubles as a landscaped park, which is as open and inviting as the pleasure cave is exclusive. Designed by Matthews Nielsen Landscape Architects, a company that has shaped swaths of New York’s waterfront, this is where Waterline Square really is. For once, the open space – a clever assemblage of lawn, pathways, stream, playground, performance stage and fountain (with the Cipriani establishment along one flank) – looks like the happiest part of the enclosure. It is both autonomous and public, surrounded by buildings but also open to the river, balanced but asymmetrical. West 60th Street cul-de-sac at the fountain. There, two driveways branch off, leading to Riverside Park South at the top of the cliff, or down the escarpment and under the highway to Hudson River Park. Private public spaces, which make up an increasingly large portion of New York’s open spaces, often function as superficial vestibules to the lettable square footage within. Here, the landscaping invites you to walk by and chase the sunset. The architecture’s lumpy crystal mounds serve as the setting for the part that really matters. This is the final twist: Finally, at least some West Siders have fared better than the compromises negotiated by their ancestors.