The Trashpicked History of NYC’s New Church

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

One morning last November, I was walking down East 35th Street near Park Avenue. It was chilly and my face was buried in my scarf, my eyes on the sidewalk. A piece of paper fluttered against my shoe, and the writing on it caught my eye. He looked old, like writing on copper. I bent down to pick it up.

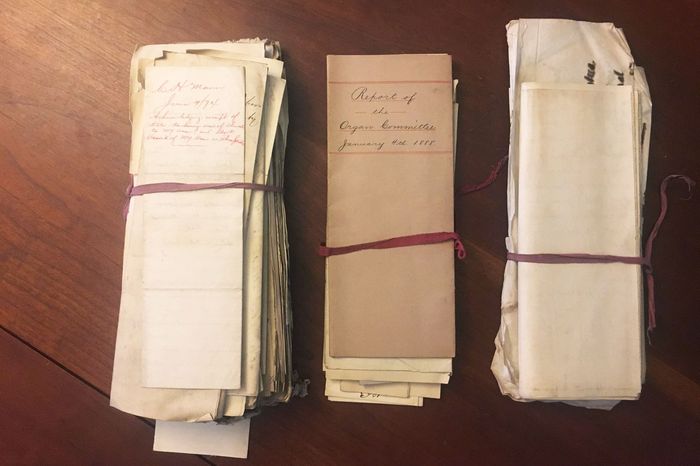

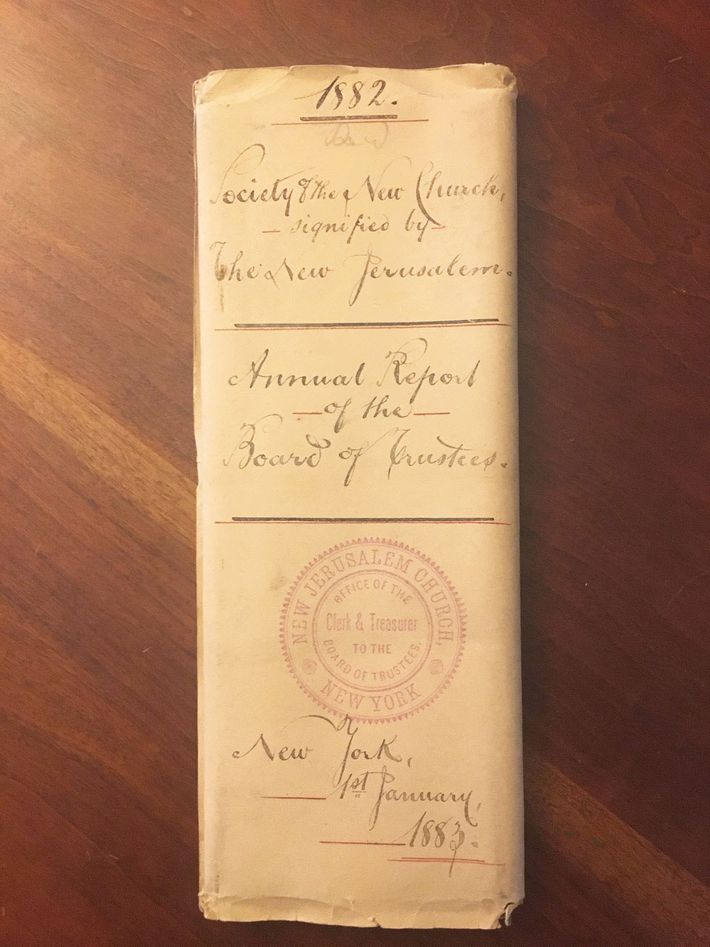

As I did so, I saw six or seven boxes of paper on the sidewalk, spilling their contents. One had a plastic cup hidden in it, almost surely abandoned there a short time before by a pedestrian, but the rest of the contents were relatively intact. I saw scores, financial records, other stuff. A box in the center was filled with this very old manuscript material. I saw documents wrapped in reddish cardboard, tied with ribbon, including one that said NEW CHURCH SOCIETY, SIGNIFIED BY NEW JERUSALEM. / ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS. / 1883. There were many more too. Scrapbooks. Letters.

By nature, I am a researcher of documents and an accidental archivist. My apartment – a few steps from this pile – contains many books, old magazines, vintage photographs. Shelves go from floor to ceiling, and they are solid. The last thing I need is another pile of old papers, I said to myself. Also, there might be bed bugs or cockroaches. And I had injured my shoulder not long before, and I couldn’t lift or carry much.

I looked down the street, toward Lexington Avenue, and saw trash bags piled up in front of every building. It was garbage day. All this would be buried in a few hours. He made it all the way from 1883 to 2021. I shook my bad shoulder as best I could, sighed, and picked up a box. A few minutes later, after dropping it at home, I came back for two more loads.

I sorted, leaving behind what was not unique: dilapidated books with their damaged bindings, photocopies of what looked like hymns. I stopped at a few large, heavy filing cabinets filled with financial records ranging from the 1940s to the present day, and left those too. Later in the week, I saw that the garbage truck had skipped the church that day, and the records were still there, so I made another haul. My wife knows me well enough to have said (with her own little sigh) “It’s okay.” Our family navigated around the pile in our hall for a few weeks while I figured out what I had.

I had made my discovery in front of the New Church, also known as the New Jerusalem Church. I already knew him a little for having lived in the neighborhood for a long time. It was the spiritual home of New York City Swedenborgiansthe Protestant followers of an 18th-century Swedish philosopher-mystic named Emmanuel Swedenborg. Their beliefs are a little hard to sum up in one sentence, but they’re not much different from Unitarians, with a strong belief in good charities and a commendable history of promoting racial equity. (They were the first abolitionists.) There are about 30 Swedenborgian congregations in the United States, and the church peaked at 7,000 members in 1900. Today there are about a quarter. What I brought home was 170 years of New York church records.

The church today.

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

The building on East 35th opened in 1859, a few years after his congregation was founded, and is by far the oldest on this street. It is old enough, in fact, to predate its neighboring buildings and therefore does not quite line up with the brownstones of the block. Aside from a misplaced entrance, it looks a lot like it did in the 19th century. The Swedenborgian congregation, by 2008, had shrunk to 18 members. As this population had dwindled by the end of the 20th century, the building had deteriorated, but church elders managed to fund a major restoration in 2008, and it still appears to be in good condition.

With the main community reduced to very few people, others began to hold services here: a Coptic congregation, Korean Presbyterians. In 2020, the Swedenborgians passed away and list the building for sale. (They dropped the price at the end of 2021, after which the ad disappeared; either it just sold or they changed their minds.) The prospect of selling the building almost surely occasioned the cleanup that sent those boxes at the curb. . (I called the church while writing this story but got no response.)

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

The contents were, to my relief, quite clean. (Not much dust, no bugs.) I left the bundles tied down for now, fearing they might be too flimsy to handle, and focused on loose items that I could unfold easily. Near the top of the pile was a document older than the building, dating from the year the congregation was founded. “The following is an extract from the minutes of a quarterly meeting…”, he said, “held at Mr. Waldo’s house, on the evening of Tuesday, October 5, 1852”.

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

It’s almost certainly Samuel L. Waldo, an important figure in the American church. He was a successful artist, and you can see his portrait of his wife, named Deliverance Waldo, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His home appears to have been on East 9th Street near Cooper Square.

The more I entered the boxes, the more there were. A report of the church’s Ladies’ Aid Society from 1907. Proof of membership documents from the 19th century. A bunch of those annual reports. Some of them were historically insignificant but vividly evoked details of daily life, such as a $125 bill for coal to heat the building in the fall of 1904. (Twenty tons, at $6.25 per person .) There was also a set of press albums from the 1930s relating primarily to another Swedenborgian church in Brooklyn and a box of photographs of that building. The prints were glossy eight-by-ten papers that smelled like an amateur darkroom, and the box of photographic paper they were in had an expiration date of the early 1960s. I soon discovered that there had been a Swedenborgian church on the corner of Monroe Place and Clark Street, demolished in the 1960s to make way for the redevelopment of the Cadman Towers. The easy assumption is that a member of the church photographed it to make a recording before it was torn down, and the recordings were all transferred to its sister institution.

The paperwork is running out at the start of the 21st century, and in its final days I spotted a few passing references alluding to the dwindling flock and church finances. The most recent items consist of photocopies and laser printouts of Microsoft Word documents. They’re less attractive to look at, of course: Times New Roman is barely written with a steel pen and inkwell, and it bears no traces of human handwriting. But they, too, are part of the significant little story of an institution’s creation, growth, decline, and near-demise.

Clockwise from top left: 1880 meeting minutes; a vehement letter from the earliest days of typewritten correspondence; Ladies’ Auxiliary Papers; statutes. Photos: Christophe Bonanos.

Clockwise from top left: 1880 meeting minutes; a vehement letter from the earliest days of typewritten correspondence; documents of the…

Clockwise from top left: 1880 meeting minutes; a vehement letter from the earliest days of typewritten correspondence; Ladies’ Auxiliary Papers; statutes. Photos: Christophe Bonanos.

It so happened that shortly before bringing all this home, I had interviewed (on a different subject) Julie Golia, the chief historian of the New York Public Library. I thought she might have some advice on what to do with all of this, and we quickly phoned each other. I started educating her. When I reached the stage of the impending sale of the church, she said, “So, did you come in or something?” I said, “No, it was all on the sidewalk.”

A beat.

“Oh my God,” she said. “Did you catch it?”

Yes, I definitely had. “Okay,” she said. “First of all, how much material is it?“A few days later she came to assess the whole thing and explained that a manageable collection like this had a much better chance of finding an institutional home than a truckload of stuff that would take years to process.

After some backstage conversations, Julie finally handed me over. The New York Public Library admissions queue, she explained, was running a little slow due to the pandemic, and she was sensitive to the fact that the pile of things in our lobby was a bit a burden. And anyway, she had spoken to Edward O’Reilly, a curator she knew at the New York Historical Society, who has a lot of religious documents from that period, and he was willing to add them to the collections. About a week later, he pulled up outside my building in a small SUV, and we gently piled the Swedenborgians in the back.

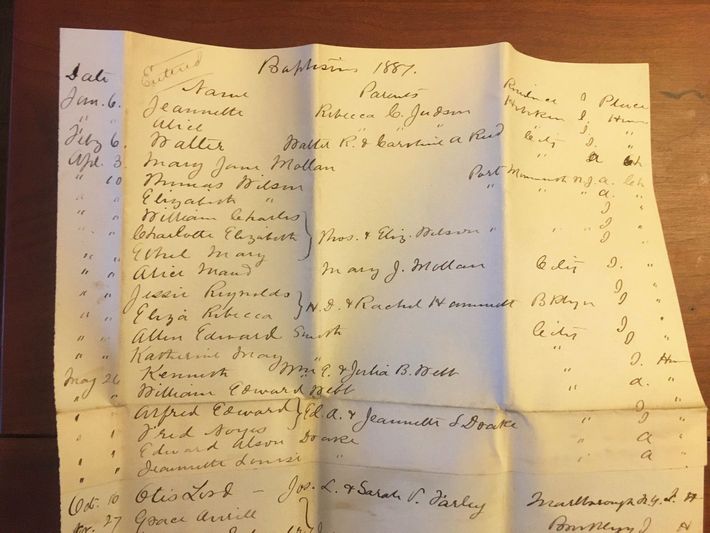

If there was one page in that cache that stuck with me, it was a list titled simply “Baptisms, 1887.” Something about all those kids, living in New York and beyond, seemed oddly immediate – because 1887 is a long time ago, but it’s not. this long. It’s two long consecutive lives. Take, for example, Jessie Reynolds and Eliza Rebecca Hammett, the 11th and 12th names on the list. Someone alive today might well remember that, I thought.

“Baptisms, 1887.”

Photo: Christophe Bonanos

So, this week, I found myself on the phone with Jessie’s somewhat surprised son, Benjamin Lacy. He is 96 years old and lives in Massachusetts, retired from a corporate law firm in Boston. His mother, he explained, was indeed born into a Swedenborgian family living in Brooklyn, although they later moved to Sewaren, New Jersey. Jessie worked as a librarian for Louis Comfort Tiffany’s studio – “or if not, for an architectural firm that was very closely tied to the Tiffany studio” – and met her future husband, Frank, when he came to the east of Iowa to commission a commemorative piece of art. . They married that fall and moved back to Dubuque. Benjamin says he’s the strange man who came back East. The family, he added, did not stick to Swedenborgianism; his father was Episcopalian, and that’s how he was raised. Towards the end of our conversation, he became curious and asked, “How did you find me?” And the answer was, in a way, It didn’t rain that day.