NYC’s Riverside Park Is Falling Apart

In a city that is still struggling to repair itself before it collapses, parks are a good measure of success. Broken benches, pitted asphalt, brown lawns and rusty slides howl problem even more clearly than falling rents and empty windows. The time, money and labor required to reverse these signs of decline keep getting worse. There is no V-shaped recovery for a park.

Throughout the year of the pandemic, I have visited and revisited parks in almost every borough: the marshes and sputum of Pelham Bay; the snowy beach of Coney Island; the monument perched at Fort Greene, shrouded in the smoke of a dozen barbecues on a hot spring afternoon; the old growth forest of Inwood Hill; the primitive hollows of Forest Park, surrounded by multi-lane roads and crossed by railroads; the straight line of the Croton aqueduct which crosses the Van Cortlandt park. And most days, I patrol for miles of Riverside Park, which spreads like a long dress off the shoulder from Manhattan to the Hudson River. The urge to go outside has given me many opportunities to examine a glorious system in various phases of distress. The fact that so many of us felt the same impulse put new pressures on parks, increasing litter and carving new paths through eroded grass.

You might expect Riverside Park to be a well-maintained star, just behind Central Park in its gloss lacquer. Long, narrow, and picturesque, it runs along some of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods (as well as social housing clusters), as well as Columbia University and a handful of other educational institutions, all of which share an interest in well-maintained open spaces. Unlike almost all of his siblings, he has his own private stash, which raises funds to plant flowers, do light maintenance, and undertake the occasional renovation of a staircase or dog track. The hills are magnets for masked citizen-gardeners, who spend their Saturdays mulching and making faces.

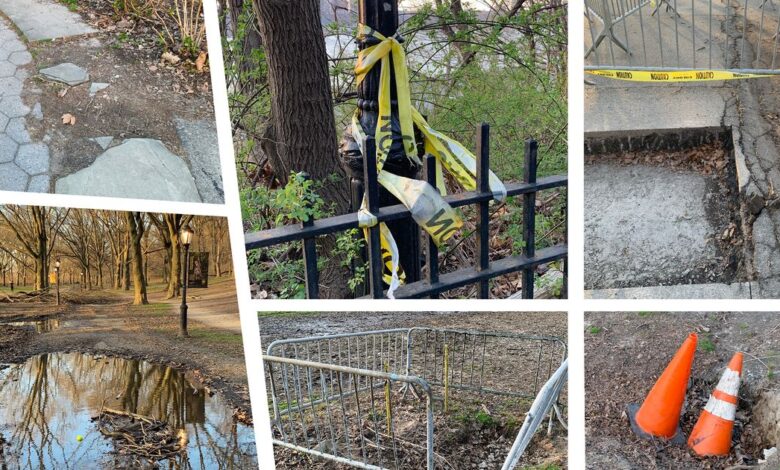

Yet in what should be the pride of the Parks Department, the state of deep disrepair is alarming and accelerating. The slabs are broken. Orange traffic cones lie in chasms. Century-old stairs have collapsed into rubble. The Soldiers and Sailors Monument, once the jewel of the Upper West Side, has been fenced off and left to gracefully decompose. A dozen streetlights always seem to flash, casting expanses of darkness favorable to attackers on winter afternoons.

The problems also arise below the surface. After decades of neglect, the drainage pipes cracked and the sumps filled with silt, so now every rain turns lawns into bogs or duck ponds. When floodwaters finally dry, they leave a cracked dirt surface. Above 110th Street, the cobblestone paths have all but collapsed and the maintenance trucks are leaving deep tracks in the mud. For years, park watchers worried so much standing water would erode the steel and concrete tunnel which passes under the park, speeding Amtrak trains between Penn Station and points to the north. In December 2019, the city allocated $ 11.5 million to study and solve the worst drainage problems in an eight-block stretch north of 108th Street, but construction on this project has yet to begin.

In 2016, the Department of Parks developed a Riverside Park Master Plan, such a comprehensive document – “ambitious” is the word used by Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver – that no one has any idea what it would cost. “It’s a monster set of needs,” says Daniel Garodnick, president of the Riverside Park Conservancy, “far beyond the city’s ability to manage all at once. The city gets rid of it: the sidewalk is repaired a few blocks at a time, a playground is renovated, a skate park rebuilt. For a dozen blocks north of 70th Street, the bikes were diverted onto their own upper path, away from toddlers and shufflers. But, especially in the stretch above 97th Street, the dilapidation continues to exceed staff’s ability to cope.

The long, cliff-side park was laid out in the 1870s, but railroad tracks and a strip of filthy industrial waterfront separated it from the river and filled the air with soot. In the 1930s, the city covered the tracks with bridges and draped the park over them. The merging of infrastructure and landscape was visionary back then, and now, in the age of climate change, it’s just as promising, but it makes maintenance difficult. The age can be brutal for viaducts and tunnels, as well as for the parks they shelter. Just ask the dangerously brittle Brooklyn Queens Highway, which is at risk of failing under the Brooklyn Heights promenade. A few months ago, in Riverside Park, the promenade that stretches between 99th and 110th streets warped in several places, like evidence of an earthquake. Metal fences rose up around the cracks and holes, preventing police cars and garbage trucks from making their usual rounds. (Cyclists bypass the barriers, digging new bike paths into the loose soil.) When I asked how severe the damage was and whether the structure – called overbuild – was sound, the parks department referred me to the ministry. des Transports, who referred me back to the parks. Neither of them offered any detail.

Then Mayor Bill de Blasio detonated an explosion of municipal largesse: $ 348 million spent on repairing the overbuild, the park’s most expensive renovation project since the 1930s and possibly the largest in all city parks. This truckload of cash comes on top of the $ 290 million allocated to rebuild 79th Street Rotunda (a cylindrical structure with a causeway on top and – in the past, anyway – a restaurant below) and the Boat Basin. This is wonderful news: in four or five (or six) years, a walk in the park might be a less amphibious experience.

To some extent, the scale of the project is related to the age and engineering of Riverside Park: a rickety park needs to be revised every century or so. But the sums at stake are also symptoms of more ordinary everyday neglect. Anyone who has ever had trouble with a leaking faucet or seen grout turn to dust between bathroom tiles turn to dust knows that the small job of today becomes the major business of tomorrow. The problem is that bureaucracies share the human impulse to procrastinate; they formalize it, in fact. The parks department’s annual spending allowance, which was reduced in 2020 and reinstated this year, fluctuates around half a percent of the city’s total budget, never enough to hold back the forces of entropy. A 2018 study by the Center for an Urban Future estimated that in most years the department has enough to cover only about 15 percent of its ever-growing needs.

“It’s subject to boom and bust cycles,” says Adam Ganser, executive director of the New Yorkers for Parks advocacy organization. “If the economy goes down, Parks is the first to be cut.” When the balloon needs or suddenly become severe, the mayor can sometimes drag large sums from one column to another. Individual city council members can free up discretionary funds or pressure their colleagues to allocate specific projects. (Private donations only play a major role in Central Park, where conservation manages the landscape on behalf of the city, and residents of some of the world’s most expensive real estate make around $ 74 million a year to guard their yards. in good shape.) New Yorkers for Parks spent much of the spring trying to keep a promise from the mayoral candidates: that they will double the Department’s share of the city’s budget to one percent, which would be transformative. . So far, Andrew Yang, Scott Stringer, Kathryn Garcia, Shaun Donovan, Ray McGuire and Art Chang have taken this vow.

When Silver, who has headed the department since 2014 and plans to step down soon, pressed his boss for more money, he did so quietly and in private, leaving the lawyers to scream and shout. Silver has been adept at handling these inconsistent fundraising flows. Realizing that the parks system reproduces other urban inequalities – residents of large areas of Brooklyn and Queens have limited access to greenery – it launched the Community Parks Initiative, a $ 318 million campaign that rehabilitated 67 Long neglected neighborhood parks in underserved areas. He claims to have cut for months the multi-year process of reconstructing a playground and points to his record of delivering hundreds of capital projects on time and on budget. Full-time staff has declined; instead, traveling teams of workers show up where they’re needed every day. But the lesson of all this managerial efficiency is wrong – that the city can become entangled indefinitely, perform the landscape equivalent of triage on the battlefield, and postpone reportable problems until they finally become too dangerous and embarrassing to be ignored. At a time when the city must make the point to all current and potential New Yorkers that this is where they should want to live, it cannot let its approach to open space be dictated by urgency and urgency. shame.