The Unsafe Design of Olmsted’s Eastern Parkway

Photo: el_cigarrito/Shutterstock/el_cigarrito

When Frederick Law Olmsted began designing the Eastern Parkway in 1870, he envisioned it as a tree-lined “pleasure road” where people could walk, ride horses, and drive carriages for fresh air. At the time, the roads of New York were crowded and chaotic, criss-crossed by pedestrians dodging carts and horse-drawn carriages. Street trees were not part of the urban landscape. The cleaner, quieter Brooklyn promenade was the first of a long series that Olmsted would draw, the American equivalent of Europe grand boulevards. They reflected his belief that parks should be accessible to everyone and that they should be connected by greenways. Upon completion, Eastern Parkway became a vital link between Crown Heights’ many enclaves, and the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission eventually designated the road as a scenic landmark, describing in 1978 as “an endless aisle of refreshment”.

He still is today. A dense canopy of elm, ash and oak trees covers the walking paths, popular with cyclists and families, and its benches are regularly occupied by friends chatting. During commuting hours, people enter and leave its four metro stations. Where the street meets Grand Army Plaza, the Brooklyn Museum and Utica Avenue, vendors sell food, books, household items and clothing. But it also became second deadliest street in Brooklyn, past Flatbush Avenue, measured by pedestrians killed or seriously injured. This year, Three people have deceased in traffic collisions on the boardwalk, and there were 62 accidents, 20 more than the same time last year, according to Crashmapper. (The total could be higher, since this only includes data from NYPD reports.) The edges are friendly, but the road itself has become a six-lane highway. Using it requires constant vigilance, a sense of insecurity that is at odds with all the remotely pleasurable emotions his original vision was intended to invoke. This year, on Olmsted’s 200th birthday on April 26, I reflected on the gap between its origins as a “shady green ribbon” and what it had become. What should be done to make the street a place that favors pleasure for all who encounter it?

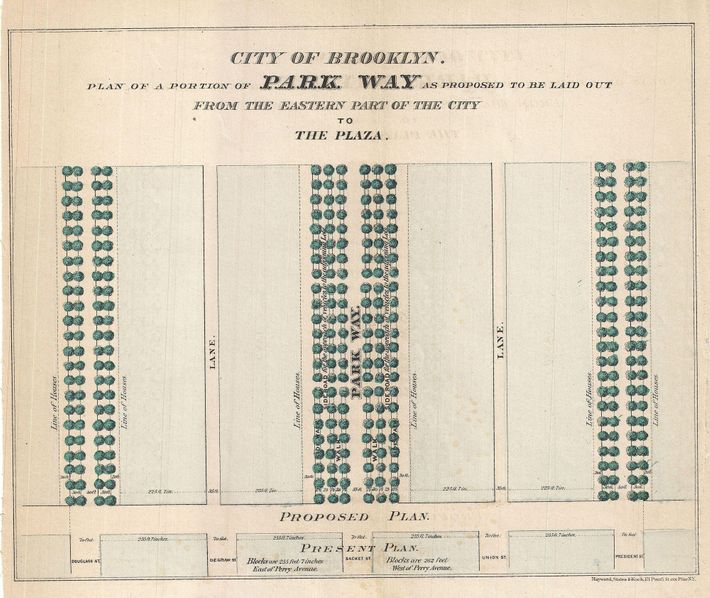

Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1868 diagram for Eastern Parkway.

Illustration: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Physically, the walk hasn’t changed dramatically. The historical The section, a 2.2-mile stretch from Grand Army Plaza to Ralph Avenue, has much the same layout as when it opened in 1874: a tree-lined central corridor, footpaths, service roads and sidewalks on either side. But the 55-foot-wide carriage ride from Olmsted’s days is now a six-lane thoroughfare. The carriage ride rough textured crushed gravel surface and the stone-covered service roads have all been repaved with asphalt. As Jessie Singer writes in There is no accident, when faced with long, straight, wide, smooth highway-like roads, drivers accelerate because they feel “safe” to do so. On Eastern Parkway, the the posted speed limit is 25 miles per hour, but drivers regularly exceed 40. At intersections, fast-turning cars encounter most pedestrians. Therefore, most car-pedestrian collisions occur near streets with a subway station or in the middle of a city block.

Although the city modified the boardwalk to make it easier to drive, it didn’t improve it much for others. There are no curbs on the North Mall (although construction has begun), making it inaccessible to the visually impaired, wheelchair users, stroller pushers, and cyclists. Delivery trucks and vans have no designated drop-off point, which means they often block service roads. As a pedestrian – I most often cross at Grand Army Plaza, Washington Avenue and Franklin Avenue – I am constantly looking over my shoulder, expecting someone to cut me off while turning or trying to beat a traffic light . As a cyclist, I usually avoid the bike path because it’s so crowded and full of uneven paving.

What’s particularly disheartening is that Eastern Parkway is getting a decent share of the city’s attention. In 2006, the Bloomberg administration created a Master to plan for the Walk to Improve the Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System, which suggested redesigning intersections, introducing more traffic lights, and marking crosswalks between malls. DOT offered the same ideas after Eastern Parkway was named Vision Zero Priority Corridor in 2015. But two more years passed before the agency started taking those steps (and hasn’t finished yet). Traffic patterns have been changed with the addition of new left and right turn lanes and changes in signal timing to keep traffic moving and reduce conflict between cars, cyclists and pedestrians. New rubber walking islands in a few intersections – at Kingston Avenue and New York Avenue – replaced the concrete islands which were briefly installed but quickly removed due to complaints that they would make it difficult for West Indian Day Parade floats to move down the road. The following a major overhaul will be implemented at Buffalo Avenue – where there have been ten accidents and 14 injuries since January, and just two weeks ago a car seriously injured a cyclist – and will similarly bring new pedestrian crossings, new signage and reconfigured traffic lanes. It’s good, but it’s far from following the traffic congestion suffocating New York City.

Anyone familiar with this street can see missed opportunities to do more. At Prospect Park, which the Eastern Parkway was to extend, the Prospect Park Alliance — the not-for-profit public-private partnership that maintains the park — has restricted vehicle accesswelcomed public–art facilitiesand started restore the landscape. A more biodiverse landscape instead of patchy grass along the road would be nice, but the park service, which runs the pedestrian malls, is stretched so thin that this improvement is unlikely to happen, especially given the attention paid to the rest of the city’s parks and parks playgrounds Desperately need. For cyclists, the DOT has installed cycle paths on the outskirts of the park. Eastern Parkway could benefit from the same. Perhaps it could also borrow from Central Park, the other masterpiece by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, which through the Central Park Conservancy added distinct interpretive signage, wayfinding and custom. trash cans and recycling bins which give it a unique visual identity and a sense of place, again made possible by the strong fundraising of the Conservancy. Likewise, historical markers explaining the walk’s past, including what was there before Olmsted built the road, such as the Weekville Cemetery which he moved, would enhance the experience of the road as a historical landmark.

Aesthetics aside, what if we designed the road to better accommodate pedestrians and cyclists? This shift in priorities is essential, according to Bill Schultheissdesign director at Toolan urban planning and engineering firm that has developed pedestrian and cyclist safety interventions to Arborway, an Olmsted-designed promenade in Boston. “What matters most is centering the values on the rules that we make in engineering,” says Schultheiss. The city has designated Eastern Parkway as a “arterial slow zonein 2014 – a contradictory concept since, according to Schultheiss, “an ‘artery’ in our business means moving a lot of traffic quickly so you can’t do things like raise a crosswalk or an intersection because it violates the fundamental purpose of the street. And I say that in the age of Vision Zero, the goal must be safety.

As many older city boulevards, Eastern Parkway was reconfigured to meet road standards during the 20th century. “If the goal is the enjoyable street experience, there are many ways to achieve that, but it’s not about keeping curbs exactly where they are and traffic flowing as fast as possible,” says Schultheiss. He suggests introducing a broader vocabulary of design interventions on the parkway, such as mid-block crossings, noting that the average distance of 1,000 feet between red lights is now too great, encouraging drivers to speed up and pedestrians to cross mid-block. “Even 600 feet is the limit,” he says. He also suggests removing parking to make room for sidewalk extensions and widening crosswalks to give pedestrians more visibility and more room to wait, a practice known as “lighting the day,” which has helped Hoboken achieve zero road deaths in four years. Schultheiss says that one of the most effective tools for slowing down traffic is a speed chart, a flat-topped raised area longer than a speed bump that he says should be installed at every intersection. Paving the main road with sections of cobblestones could also force people to slow down.

To avoid deaths like the one that happened last year, when a driver Utica Avenue Drag Race killed a woman and injured a man near the parkway, the streets that intersect Eastern Parkway also require significant traffic calming interventions. Olmsted’s plan for Eastern Parkway also considered the surrounding areas, limiting development around the parkway to residential use (nearly 50 years before New York City was zoned) and banning harmful land uses to preserve park-like sensibility.

While traffic deaths — up 44% in 2022 — Reaching the highest level since the introduction of Vision Zero, New Yorkers need more aggressive action to make city streets safer. It starts with how we design them in the first place, like Olmsted did when he designed Eastern Parkway around the pleasure principle. It’s what made the road novel in the first place and why so many people still enjoy it today. But his death is unlikely to change through incremental patches. While Eastern Parkway needs new traffic lights and curbs, it also deserves bolder interventions worthy of the public resource that it is.