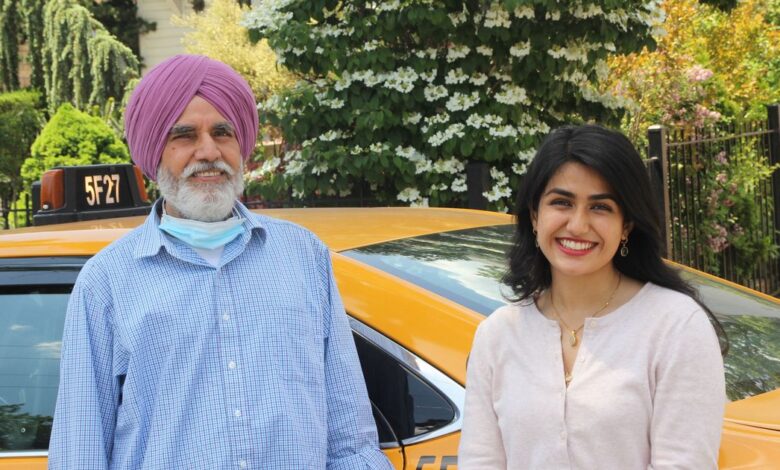

A Cabdriver Father and His Daughter on the Campaign Trail

Photo: Courtesy of Jaslin Kaur

During the election campaign, city council candidate Jaslin Kaur said it was her father’s struggle with a taxi medallion debt that inspired her to represent District 23 in East Queens, where she served. grown up. Like many of the city’s taxi drivers, Kaur’s father, Partap Singh, contracted loans to be able to pay for his taxi medallion in 1993 and still work ten hours a day to be able to reimburse him and take care of his family. When the the medallion taxi market has collapsed in 2014, he found himself with a now undervalued locket and about $ 130,000 in loans to repay. Thousands of drivers across the city have seen their lives decimated in the same way, and desperation and overwhelming debt have even led some to take their own life. Despite the extent of the crisis, the city has done little to help drivers like Singh recover.

Kaur, 25, works on a platform that includes creating a driver’s retirement fund and offering debt relief and has been endorsed by Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Working Families Party. We spoke with her and her father, Singh – who immigrated to the United States from the state of Punjab, India, in 1985 – about the medallion crisis and her experience of driving cabs over the years.

Kaur: When I was growing up and going to school, sometimes they had career days where they asked you to fill out a little form: What are your parents doing? I had other friends who said, “My dad works in the bank. “My father works as a firefighter. “He’s a policeman.” But I didn’t know how to explain what my father was doing. So I would say, “Well, he works in town,” which is true because he rides all over town. I distinctly have these memories of going to bed early to get up for school but always hearing the commotion around three or four in the morning because he got up so early for a shift to drive the cab. . And so sometimes I would go downstairs just to say hello at three or four in the morning. These are some of the best memories I have of knowing how many hours he would devote each day.

Of course, I really worry about him. Over the years, he has had two eye surgeries. And when he was working nights it puts a lot of strain on your physical health. And even just the mental health checkup too. Like, right after we’re in post 9/11 New York, for a lot of Sikh Punjabis, a lot of South Asians in New York City, we were often the target of surveillance, we are the target of racial epithets. It really hurt members of our community.

Singh: The hardest thing about driving a cab in years was when September 11th happened. People hated us. We didn’t know when someone could attack us. And there was no business in town at all. We were going all over the Bronx, to Brooklyn, trying to find rides. It was very hard to survive. We were so scared of what would happen to our families, and we were so scared that something would happen to me in my taxi. People called me bin Laden.

Kaur: I remember at one point he wore a baseball cap instead of his turban. He tried not to be such an obvious target for some of the people who would be his passengers and threw some really horrible racist things in the back of the cab.

Singh: After September 11, we had a lot of mics and we made a lot of money. My plan was to work hard and have enough money to survive. Also, I had two young children, so I wanted to pay for their college. I didn’t want them to take out a loan or anything for their college.

Kaur: When did you realize this was going to be a major issue with the medallion crisis? Was there a time when you realized how difficult it was going to be?

Singh: In 2014, when the medallion market collapsed, Jaslin was going to college and my son was also going to college, George Washington University. So I was totally upset; my credit card was full. I didn’t know how I could cover everything because I didn’t want to lose my children’s education. Even now, it is still a very difficult time for me. I’m 62 now, so I can’t work overtime. The last two years have been very hard for me.

Kaur: For me it really came down to when we were trying to raise the money to continue my education. And so growing up, I think, especially in an immigrant household, you are often not told what the finances are. Your parents just tell you, “Yeah, well, we’ll find out. Do not worry. But underneath these layers you understand that there is something very serious that is wrong. That there is some kind of pressure that your family is facing, because they are working a lot more hours or suddenly you are not buying certain things. And that’s how when I had to apply for college – and I think that’s what happens to a lot of kids when they have to fill out their FAFSA forms – they started to understand their income. family. They are starting to understand how much money we have and how much more money you can get. And that was a moment of clarity because I had to sit line by line and go through tax forms with my parents that I had never seen before, until I was 18. And it was such a crystallized moment to understand, Oh, we’re really not doing that well. Even though I live in a big house, I think my parents did a great job trying to protect me from it.

Singh: Most people have lost their house or their locket. Everybody tried to give their kids a good education, but all of a sudden, you know, it all fell apart.

Before Uber and Lyft came along, the city was selling lockets for millions. I bought mine for around $ 140,000 and owe $ 130,000. The credit unions gave us loans to pay off 80% to 90% of the debt. I thought it was a good investment, that I could survive, me and my family, while paying off the medallion mortgage.

Kaur: We were with Melrose, weren’t we?

Singh: Yes.

Kaur: So we had the Melrose credit union, and even that credit union, which mainly handled medallion loans, is now almost fully liquidated. This says a lot about the fragility and precariousness of the medallion industry under our leadership of the mayor of the city.

A locket is often a promise that you can finally afford and put a mortgage on your house, move to the suburbs and buy a house, send your kids to good schools. And then, around the year that email services like Uber and Lyft entered the city, that was around the time the locket market was crashing. I had to drop out of college because we could no longer afford the tuition fees. And even though I was finally able to finish my studies, we had spent so much time trying to get me into a really good private school, and it just wasn’t a viable option for us anymore. I really think a lot of what is guaranteed with a locket has really collapsed with email services like Uber and Lyft.

Singh: Because of Uber and Lyft, I lost everything, and now I don’t even have my health. I have no pension costs. I have no deposit money in the bank. So I depend on everything I work on every day. I still work ten hours, six days a week.

Kaur: And then he goes into the countryside afterwards.

Singh: After that, I have to campaign for three or four hours – my days are almost 14, 15 hours. I am very excited about the campaign. I do everything to make Jaslin successful in the countryside.

Kaur: [Our relationship] got closer, I think now that I’ve finished school, because a lot of times we just didn’t see each other because of her work schedule. So if I was in school, I would come home and he would still be at work, or I would only see him very early in the morning. But I think this is definitely the countryside he comes to the office all the time.

Singh: At first, I was so surprised that I didn’t even think of Jaslin as a candidate for city council. I didn’t even know she could run for city council. Now I think because my daughter is so smart I think she is going to town hall and maybe somehow she will solve the crisis problem medallions. We will have someone at Town Hall to bring up the kinds of issues that we face on a day-to-day basis – so that we can have a say in Town Hall.

Kaur: It was always great growing up in a family where I had the choice to be what I wanted. We have a Punjabi saying, like Jo tusi choundey ho, down oh hi karo – whatever you want, do it. And so it’s really great that no matter what the dream is, they’re always there to support no matter what. Now he campaigns every day. He’s knocking on doors. He makes phone calls. And he’s been at the polls all through early voting so far.

Singh: We want to do something for the taxi drivers. It’s very simple, you know: Uber has over 70,000 drivers and only 12,000 taxi medallions, so if the city wants to do something about taxi drivers, they can cap the number of Uber taxis. The yellow taxi is over 100 years old; we are city drivers, but the city is not helping at all. Do you remember September 11? [For] at least more than a month, we offered free service to the people. We have helped the city, but the city does not want to help us.