Should It Be Easier to Take Away a Driver’s License?

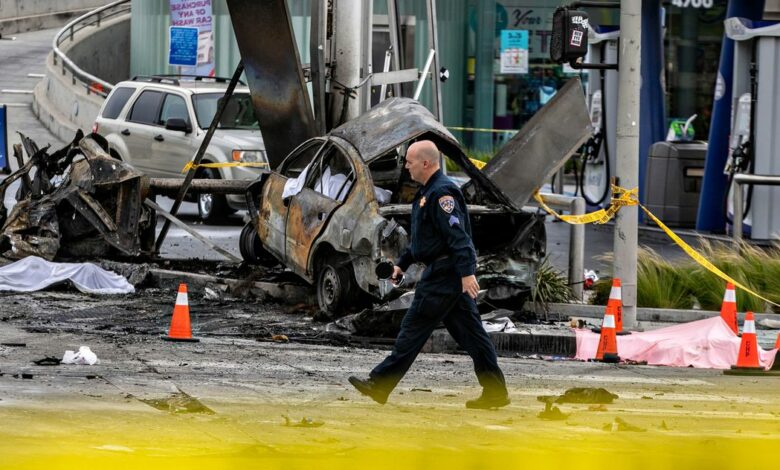

CHP and other officials are investigating a violent crash where several people were killed near a Windsor Hills gas station at the intersection of West Slauson and South La Brea Avenues in Los Angeles.

Photo: Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The afternoon of August 4, Nicole Linton blazed through a red light at the intersection of La Brea and Slauson in South Los Angeles. According to Highway Patrol estimates, she was 90. After hitting several cars, the Mercedes-Benz she was driving eventually hit a pole at a gas station and exploded. The smoke from the fireball could be seen for miles around. Six people were killed, including an 11-month-old child and his pregnant mother, whose 8.5-month-old fetus was ripped from his body by the force of the collision. Linton survived with only a few broken bones. She appeared in court the following Monday in a wheelchair, an elastic bandage wrapped around her elbow, and cried several times during the hearing, where she was charged with six counts of murder.

The accident was a convergence of overlapping crises: a nurse who had spent the pandemic traveling to different states for work, increasing prevalence of speeding on the streets of the United States during those two and a half years, and a corresponding increase in the number of road deaths nationwide. But in this case, prosecutors also said Linton had a history of dangerous driving. They allege that she was involved in 13 previous accidents, including one in 2020 that totaled two vehicles and injured someone, after which she had to take a defensive driving course. With that kind of record, she just shouldn’t have been behind the wheel. So why was she?

The social contract that Americans make every time we use an American street is based on a system of regulation and enforcement that is, in theory, supposed to protect us from the dangerous act of driving. State motor vehicle departments license drivers and license vehicles; federal agencies such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration ensure that these vehicles are, ostensibly, sure. A network of overlapping departments, from federal to municipal, designs the streets, which are patrolled by law enforcement officials. The requirements to get and keep a driver’s license vary from state to state, but the general rules are the same: break the law too many times and that license will be revoked. In reality, however, this system is designed to fail in places that, except require the use of a car. In many states you can’t work without driving, you can’t earn money, you can’t see your friends and family. Taking that privilege away, for whatever reason, may seem grossly unfair – but in a country where more than 40,000 people are killed by cars each year, the fact that so few drivers lose this privilege. “Much of what is encouraged in politics and politics is ingrained in our car culture,” says Josie Duffy Rice, a criminal justice expert and writer. (Full disclosure: she is married to my New York colleague Zak Cheney-Rice.) “Our political structure is just very bad at implementing real solutions to the problems we face, and very good at implementing the consequences of the problem.” As she watched the video of La Brea’s accident, she thought of prevention rather than punishment. “How do you prevent something like this from happening?” And can we? Can we totally rule out the possibility of someone doing something like this in the future?

During the pandemic, speeding and drink-driving – which accounts for two-thirds of road fatalities – have increased, mirrored by an increase in the number of fatal accidents. Federal data released this week shows a 7% increase in road deaths for the first quarter of 2022 compared to the same period last year, and a 22% increase compared to 2020. During these same two years, the repression of dangerous driving dropped in major American cities. In New York, the number of dangerous driving tickets issued by the NYPD in 2022 is down by half since 2019. Even automated application programs do not work as expected. The city one project to seize vehicles who receive five red lights or 15 speeding violations per camera over a 12-month period have only taken five cars off the road. In San Francisco, a in-depth report this week shows similar data trends with an even more troubling conclusion: “The SFPD issues tickets to San Franciscans, especially marginalized groups, who commit minor traffic violations, while doing an inefficient job of doing respect the most dangerous driving behaviors on our most dangerous streets. .”

If enforcement isn’t effective, what about focusing on stricter suspensions for people based on proven incidents, like accident history? Thanks to an agreement reached in the 1970s, it should be easy for DMVs to share information about collisions and violations between states. But these systems are outdated – some databases date from the same era – and bad pilots often slip through the cracks. Just last week, a jury acquitted Volodymyr Zhukovskyy, truck driver with a horrifying driving record that killed seven motorcyclists in a New Hampshire crash in 2019. A federal investigation had determined that Zhukovsky was impaired by heroin, fentanyl and cocaine on the day of the accident, and added: “At the time of the accident, [Zhukovskyy] had a suspended license in Connecticut, which was entered into an electronic system that alerts other states and should have driven Massachusetts RMV revoke his license. The crash was the subject of a Boston World investigation and documentary which demonstrated how these simple data tracking failures are keeping thousands of drivers on the road who shouldn’t have a license. This piecemeal system is unlikely to improve; there is political resistance to a true federal database, similar to the fight against a federal database for guns and their owners. And as Zhukovskyy’s acquittal demonstrates, driving is considered such an essential privilege that even judges and jurors in dangerous driving cases are less likely to wrest it away.

Oddly enough, many people lose their license – for reasons that have nothing to do with driving. Because the driver’s license has become this country’s de facto identity card, the system is as unfair as traffic control, says Miriam Pinski, who holds a doctorate in urban planning. and research analyst at Shared use mobility center, who is writing a book on the history of driver’s licenses. Because governments have no other way to track information such as court records, license revocation has become a punishment for things like non-payment of child support. “There are all these broken glass laws on the books that we use driver’s license suspensions for,” she says. “We’ve shifted focus to what the DMV actually does.” Some reforms are underway. California recently licenses reinstated levied on people who suspended them for reasons entirely unrelated to dangerous driving, such as a missed court date or late parking tickets. Last year, New York passed a law that no longer allows license suspension for failure to pay a fine.

The La Brea crash that killed six people, more than just the fatal consequence of the actions of a single driver, was a product of his environment. The car was missing a on-board cruise control, a simple intervention that can prevent drivers from exceeding the limit, as new cars sold in Europe already do. two roads which look and function like highways have been repeatedly expanded into fast traffic channels in the quest for self-reliance. Skid marks that traced jagged circles on the street – not from the accident itself but from previous incidents of street racing — offered proof that the intersection was already a problem. A punitive measure like revoking a driver’s license cannot follow without preemptive investments in auto manufacturing and street design, Pinski says. “We created these vehicles and built these cities that facilitate speed,” she says. “And now we’re punishing people for using the system we designed?” There must be a system in place to hold accountable drivers who break traffic laws; they put people’s lives at risk, she said. “But what we should really be asking for are alternatives so people don’t have to drive.” And even taking someone’s license away doesn’t guarantee they won’t drive, she adds. About three-quarters of people who lose their license continue to drive, often because they have to use their vehicle to get to work or school. They do not have the choice.