The Gentrification of the Lower East Side in the 1980s

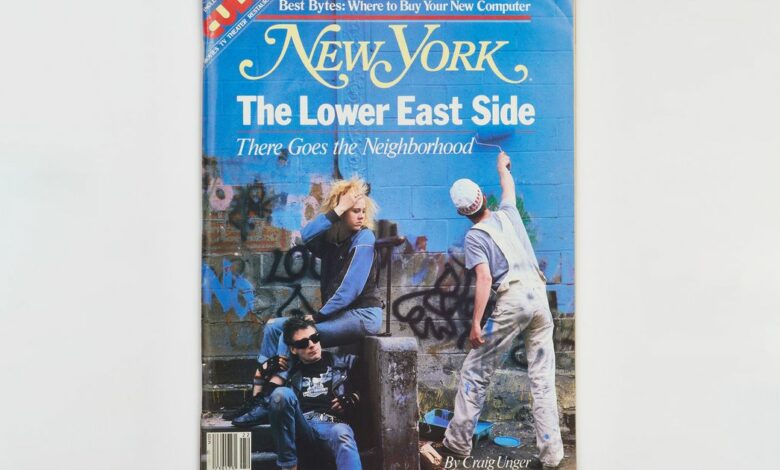

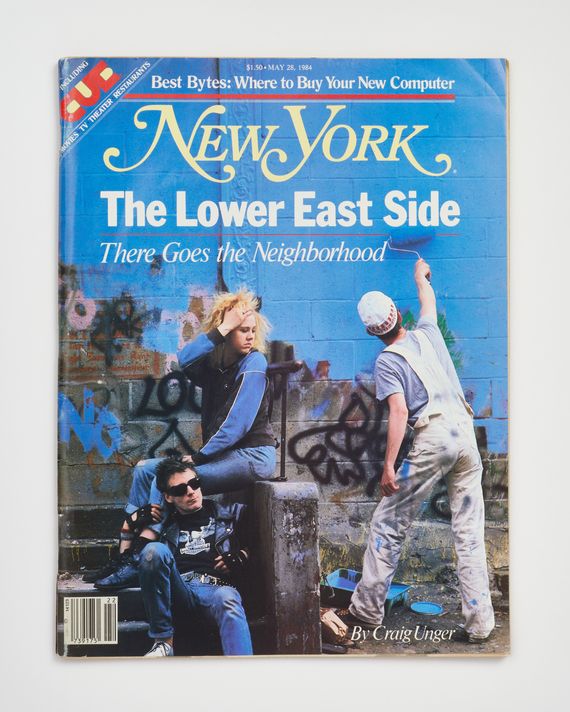

From the May 28, 1984 issue of New York Magazine. This article was featured in Reread: Real Estate Mania, a newsletter miniseries that resurfaces classic stories of ever-rising rents, the next hot neighborhood, and some truly nightmarish living situations from the New York archives. Sign up here to read them all.

The talks dragged on past midnight, but George Jaffee, a Brooklyn real-estate developer, refused to budge. For reasons that he couldn’t quite fathom, he was in a terrific position. A young man named Harry Skydell was wildly eager to buy the Christodora, a clunky old Lower East Side building that Jaffee owned. The developer had insisted on difficult conditions, and still Skydell kept running out to huddle with his partner, trying to find a way to buy it.

“He was like a little kid begging for his first lollipop,” recalls Jaffee. ” He was so desperate to own it. He would have signed anything.”

Skydell’s enthusiasm was indeed mysterious. The sixteen-story building he wanted to buy, on Avenue B facing Tompkins Square Park, was surrounded by burned-out buildings that crawled with pushers and junkies. It was boarded up, ripped out, and flooded. The electrical system was almost nonexistent; the plumbing didn’t work. Even the exterior trim was starting to crumble. Early in the seventies, the city had put the Christodora up for auction and nobody bid. Jaffee, a 51-year-old specialist in subsidized low-income housing, had finally bought it in 1975, after the minimum bid had dropped to $62,500. He was the only one who made an offer.

And yet, eight years later, Harry Skydell was keeping Jaffee up late at night, trying to work out a deal. “We’ve got to settle tonight,” Skydell insisted. Jaffee grumbled. He was flying out early the next morning on a Mexican vacation. Skydell refused to leave. At one in the morning, the deal was finally set. Skydell agree to virtually all of Jaffee’s conditions — including a $1.3-million price tag.

Within hours, Jaffee was on a beach in Acapulco, reflecting on his 2,000 percent profit. And 26-year-old Harry Skydell, a lawyer with all of four months’ experience in real estate, was making plans to fix up a 55-year-old building that looked as decrepit as the neighborhood it towered over.

Gentrification is a familiar story in New York City. Spurred by an epic shortage in rental housing, tens of thousands of young, middle-class professionals have moved into and spruced up sagging neighborhoods — Park Slope, Chelsea, the Upper West Side, SoHo. But nowhere have the tensions and dramas of this phenomenon been more starkly displayed than in the area known variously as the Lower East Side and the East Village.

Actually, the Lower East Side and the East Village are two distinct, though overlapping, communities, separated by class, history, and style. The Lower East Side is the historic New York melting pot. Ranging from about 14th Street to Chinatown, it’s the neighborhood where immigrants have settled for 150 years. Today, the poverty and decay notwithstanding, it remains an extraordinary conglomeration of ethnic groups — principally Poles, Ukrainians, Chinese, and Puerto Ricans — and several generations of bohemians.

The East Village refers to an area between Houston and 14th Streets, bounded by the Bowery and the East River — roughly the northern part of the Lower East Side. Most of the accents heard in the East Village these days don’t belong to immigrants. More likely, they’re attached to art collectors who’ve just jetted in from Europe, for this old neighborhood has suddenly turned chic. Art galleries are sprouting everywhere. Boutiques and charcuteries are offering things never seen before on these mean streets. And real-estate values are exploding. From newcomers like Harry Skydell to old hands like Harry Helmsley, developers are sweeping in, looking to make deals. Some people who have lived there for years are understandably unhappy, particularly many of the shopkeepers who are unprotected by rent control. Others are mostly bemused. “I’ve lived in my rent-controlled apartment for years and pay $115 a month,” says one man. “I live on the Lower East Side. The young kids who just moved in upstairs and pay $700 a month for the same amount of space — they live in the East Village.”

There is unquestionably a certain madness to what’s going on. The owners of a bar called Beulah Land display works by graffiti artists, yet they worry about kids spray-painting the exterior of their place. Art collectors interrupt their scouting to make sure the hubcaps haven’t been swiped from the Mercedes. Diners at Evelyne’s sample French delicacies just a block from the men’s shelter, where homeless alcoholics sprawl on the sidewalks. Two-bedroom apartments in ex-tenements rent for up to $2,000 a month. Even the “Big Vinny” memorial, an abandoned structure on East 3rd Street that the Hells Angels have dedicated to a fallen comrade, is rumored to be going co-op. And meanwhile, a huge, unusual building surrounded by crime, decay, and poverty keeps changing hands for millions of dollars.

In 1898, two young women, Christine MacColl and Sara Libby Carson, launched a nondenominational settlement house at 147 Avenue B and called it Christodora House. It taught arts and crafts and offered classes in English. On the Lower East Side in those days, there were plenty of takers. Since the first tenements had gone up in the 1830s, the area had been home to virtually every wave of immigrants to hit these shores. By the time Christodora House was formed, the Lower East Side was one of the poorest and most densely populated communities in the world, with more than 700,000 people crammed into about two square miles.

The settlement house did well in that environment and eventually outgrew the four townhouses that were its home. In 1928, they were demolished to make way for a “skyscraper settlement house” — a sixteen-story brick building financed by railroad baron Arthur Curtiss James. The Christodora, as it became known, was a remarkable building in its heyday. The exterior, though modest, was decorated with classical and Art Deco motifs. The upper floors served as a residential hotel, the profits of which were to subsidize the settlement house. The top floor had a dining room, a roof garden, and a solarium. The lower floors included a concert hall, a paneled library with large fireplaces, a 50-by-20-foot swimming pool, a theater, a gymnasium, and classrooms.

People who grew up in the neighborhood during the thirties recall the Christodora as a fabulous recreational facility. In those days, the area around Tompkins Square Park was hardly wealthy. “But there wasn’t any real poverty,” says Phil LaLumia, superintendent of the Boys’ Club on East 10th Street and a former president of a Lower East Side Democratic club. “The area was filled with light industry, so that people in the neighborhood could walk to work each day. Between 14th and 11th Streets was Italian. On 7th and 8th and 9th Streets were Slavs, Poles, and Ukrainians. Avenue B was Jewish. These were all communities within themselves that lived side by side but didn’t mix.”

In the forties, however, small industry left the area. After World War II, many veterans moved out. One victim of the area’s declining fortunes was Christodora House. By 1947, with the hotel not making enough money to subsidize the settlement house, the building was sold to the city and taken over by the Department of Social Services.

Still, the Lower East Side remained a magnet for new immigrants. Thousands of Puerto Ricans arrived. But with no major industry or business to employ its people, the neighborhood began to deteriorate. The Christodora was a bellwether. In the late sixties, Social Services left the building, and the city turned it over to about fifteen community groups, including the Black Panthers and the Young Lords. One of the groups got caught up in an internal political dispute that erupted into a pitched battle. The water valves on the fifteenth floor were opened, destroying the electrical system. The subbasement flooded. “If you slipped off the third step of the basement, you would be sucked into a dark hole filled with water,” recalls Father Patrick Moloney, a Melkite Greek Catholic priest and a neighbor of the Christodora. “lt was a death trap. I saw it happening to that wonderful building. It became an empty, abandoned tomb.”

In the seventies, hundreds of buildings in the area were likewise abandoned. “There was a time,” says one developer, “when the only thing that could be done with many buildings in this neighborhood was cut services, burn them, and run.” Arson became a growing local industry. “These were buildings with no heat, no hot water, no locks,” says Sister Elizabeth Kelliher, a Roman Catholic nun and a member of the Loisaida Economic Development Corporation. “The landlords had wrung all the money they could get out of them. And when they were caught years behind in their taxes, the last money they could get out of them was to collect the insurance by setting the buildings on fire.”

Today, whole blocks between Avenues A and D are lined with the carcasses of buildings. Vast stretches of land are covered with crumbled brick and cement. Until recently, lines of drug buyers snaked around the blocks. Dealers paid children to steer prospective clients their way. Scores of cars with out-of-state plates cruised the area in search of heroin.

When Father Moloney found a dead body near the Christodora last year, the police acted almost unconcerned. “We are in a no man’s land,” he was told. “They can dump anything they want here.”

The pressures that come together to gentrify a neighborhood are at work long before the first signs of change appear. In Manhattan, those pressures include a housing-vacancy rate of 1.9 percent and an influx of young, eager newcomers. There’s also a history here of making over neighborhoods and — probably headiest of all — a dramatic record of fortunes being made as real estate turns over. SoHo, which went from a decayed manufacturing area to an international synonym for New Wave art and culture, is only the most talked-about recent example.

As in SoHo, the harbingers of change on the Lower East Side were the art galleries. In July 1981, Patti Astor and her partner, Bill Stelling, opened the Fun Gallery, on 10th Street near First Avenue, selling works by graffiti artists. “It was just a party really — an art party,” says Stelling. “It was our way of doing a takeoff on the serious SoHo art galleries.”

Other galleries soon followed. In the spring of 1982, a young woman named Joanne Mayhew-Young (better known today as Gracie Mansion) turned the bathroom of her 9th Street railroad flat into an exhibition space. By that November, Gracie Mansion was able to draw 1,500 people to an opening at a temporary space on St. Marks Place. The street was jammed with limousines that, for a change, weren’t carrying drug dealers. “It was too good to be true,” says Gracie Mansion, 37, between calls in her 10th Street gallery. “I didn’t want to be an art dealer. I got pushed into it.”

Today, dealers from the biggest galleries in SoHo and the 57th Street area forage the East Village regularly. Museum curators keep a close eye on it. The Guggenheim has twice sponsored tours for its members, punctuating the outings with brunch at the Pharmacy, a new restaurant on Tompkins Square Park. A map of the galleries issued in January shows 30 — and already it is out of date.

Just as the SoHo artists created their own world in the early seventies, sneering at the uptown art establishment, so the East Village now chides SoHo. “Whenever I went to SoHo, I’d see these gigantic pieces that didn’t relate to an average person,” says Gracie Mansion. “They were for museums or public spaces. And the same artists were shown over and over again. The entire scene there was so entrenched it couldn’t accommodate a new generation of artists. It was an impossible place to break into. But there was so much artistic energy here that we said let’s do it ourselves.”

In doing it themselves, the East Villagers have remade their neighborhood. Major retailers such as Conran’s on Astor Place and Tower Records, on 4th Street and Broadway, have opened for the new gentry — though these big outlets have stayed safely on the western edge of the area. More typical are small boutiques, restaurants, and food stores. Gary Feldman and Paul Campbell began making salads in the back of a Korean produce mart and displayed their meals in a milliner’s case. In early 1982, they got a storefront on Second Avenue and opened a gourmet deli, Bink & Bink. Vincent Melilli, an antiques dealer who was driven off Columbus Avenue by high rents, retreated to Avenue A, where, last year, he opened V. Foods, another fancy deli. An art-school sensibility pervades many of these places. Beulah Land, on 10th Street near Avenue A, offers cocktails, performance art, and exhibits. The Limbo Lounge, on 10th Street near Avenue B, serves soda to an art-gallery crowd. And 8 BC, just west of Avenue C, on 8th Street, provides late-night music and performances in a bomb-shelter-like environment.

The Life Cafe, on 10th Street and Avenue B, serves chili and beer to both the gallery crowd and the local poor people. But it is an exception. For the most part, the old Lower East Siders don’t have much to do with the new East Village merchants.

“The art galleries bring in the fancy restaurants, and that plays a big role in making this an upper-class neighborhood,” says Chino Garcia, executive director of Charas, a local community organization. “With no commercial-rent control, all the small, inexpensive restaurants have closed down, the goods and services are being forced out. And what is replacing them is a hell of a lot more expensive.”

Deborah Humphreys, director of Pueblo Nuevo, a community housing organization, says that two years ago the average rent in the neighborhood was $150 a month. “Now it’s $600 to $1,300. It’s tense. Indirectly, the artists are gentrifiers. They supply the housing demand that causes rents to be out of reach for low-income residents. It really hits the poor people who have always considered the Lower East Side home. Where can you go if you can’t live there?”

Even before the first gallery opened up, the Christodora was attracting a few sparks of interest. “I showed it to at least four or five parties starting in 1980,” says Rose Edwards, a broker who specializes in the East Village. “Even going inside was a sign of fairly serious interest. With the doors of the building soldered shut, that meant bringing a welder.”

George Jaffee, who owned the building, says he was not actively trying to sell it. He claims he was trying to get federal funds for a low-income project, but the money never materialized. Meanwhile, the Christodora was becoming a classic speculative property. The taxes and finance costs were minimal. And as the area began to develop, the offers began to go up — from $200,000 to $400,000 to $800,000. By late 1982, several buyers said they might be willing to pay more than $1 million. Robert Weiss, a 29-year-old dye-company executive, investigated, but decided he had not looked into the area enough to risk so much money.

Sam Glasser, one of the pioneering developers in the area, led a group of interested buyers. Earlier that year, he’d renovated a vacant nursing home at 131 Avenue B, just half a block away from the Christodora. Offering 40-foot-long living rooms with unobstructed views of Tompkins Square Park — the largest public square in Manhattan — Glasser put eighteen units on sale at prices of up to $110,000. All were bought up within six weeks, without being advertised. The new owners included a designer, a restaurateur, a journalist, an antiques dealer, a librarian, a bond trader, a carpenter, and an architect — most of them in their early thirties.

Yet another suitor of the Christodora was a partnership led by Harry Skydell. A 1981 graduate of Yale Law School, Skydell had given up his job in a law firm to pursue real estate. “The first thing that got me interested was when a friend bought a building on Ridge Street, below Houston, renovated it, and rented small loftlike spaces for about $600,” says Skydell. “It was on the corner of nowhere.” By early 1983, Skydell had paid prices as low as $70,000 for five small buildings in the area around Tompkins Square Park. “That was the first step,” says Skydell. “The next was to find a property that would stabilize them, that would make them more valuable.”

Relatively speaking, the East Village is a valley in the Manhattan skyline, with few buildings more than four stories high. Against this setting, the Christodora is monumental. “It hits you in the face,” says Skydell. “When I first saw the Christodora in 1982, I was driving around with my partner Judah Klausner, taking notes about various properties. There was a moment when it hit me: This is the one to do. I saw this as the cornerstone of all the development in the area.”

“It’s beautiful inside,” says Paul Bridgewater, a colleague of Sam Glasser’s. “It’s a shambles, of course, but you can see the potential — the high ceilings, the swimming pool, the gym, the stage.” From the terraces on top, the building offers spectacular views. Toward the north, the skyline is dominated by the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and Rockefeller Center. Toward the east, the East River is visible from 59th Street to the Brooklyn Bridge. The view south, over the financial district, bumps into the World Trade towers, and to the west, you can see across the Hudson.

Of course, if you lean over a terrace and look straight down, the view is far less appealing — and it was particularly bad in 1982. Rubble was everywhere. Junkies were lining up for their scores. And the one big co-op in the area, 131 Avenue B, was so isolated that its iron gates had to be draped with barbed wire. “I figured if these people were willing to pay so much, they must know something I don’t,” says Jaffee. “But I drove around and I couldn’t see the difference.”

By Friday, February 4, 1983, the two most serious bidders for the Christodora were Skydell’s partnership and Glasser’s. Both groups knew Jaffee was leaving for vacation. “At 4 p.m. on Friday, he called and asked us to come in at 9 a.m. on Monday with $100,000,” says Paul Bridgewater. “That was after the banks were closed! So we spent the weekend running around like maniacs.” On Sunday night, Bridgewater got another call from Jaffee. “This time he told us to add on another $15,000 to cover his architects’ fees. I must have called twenty people trying to come up with the money.”

By Monday, Bridgewater and Glasser had lined up the commitments for the $115,000. But picking up checks took the entire morning. They arrived at Jaffee’s Court Street office, in Brooklyn, shortly after noon. Over the next two hours, they found they were unable to meet the developer’s terms.

After they left, Jaffee had one more call to make — to Harry Skydell. “He was so persistent,” says Jaffee. “He wouldn’t let me breathe.” Within 45 minutes, Skydell was at Jaffee’s office. He left after ten hours of negotiations, taking with him a signed contract for the purchase of the Christodora.

The Christodora’s development still carried enormous risks. The biggest problem was crime. “The drug scene was completely out of hand when we bought it,” says Skydell. “People were afraid to walk around.” Banks were hesitant to lend in such a neighborhood — and without large loans, the Christodora’s renovation would be impossible. And just because eighteen units in a nearby co-op had sold quickly didn’t mean that the Christodora, nearly five times as big, would be as popular. As it turned out, though, Skydell’s error, if he made one, was in underestimating the speed with which money moved into the East Village.

By early February this year, the area around the Christodora resembled an armed camp. Operation Pressure Point, a major crackdown by city cops on drug dealing, was under way. The mounted police parked their horse vans in Tompkins Square Park. Desolate intersections were staked out. More than 150 cops, working two shifts a day, covered the area. Big-time dealers were said to have buckled under the pressure by sending their pushers on paid vacations — even chartering flights to the Caribbean for them. Still, more than 4,000 drug-related arrests were made in the first three months of the operation.

A lot of people wondered where the police had been before. “Those drugs were tolerated for years,” says one local man, “but that was before real estate was worth anything here.” And some people pointed out that most of the arrests were for junkies, who would be out on the streets in days.

Overall, though, both merchants and local people think the crackdown has been enormously effective in helping to revive the neighborhood. By late winter, families on Avenues C and D could feel safe walking outside with their children.

Even before the crackdown, merchants had been flocking to the Tompkins Square area. In late 1982, Sam Glasser helped a group open the Pharmacy. Serving Sunday brunch and salade niçoise, it became a favorite of the art-gallery crowd. Last November, Paul Bridgewater lured Evelyne Barthelemy from the kitchen of a local hangout and started Evelyne’s, the neighborhood’s first elegant French restaurant.

Real-estate prices hit new highs. Many families still lived in large, rent-controlled apartments for as little as $75 a month, but the renovation drive pushed farther east. The rents for redone apartments in bombed-out sections of Avenue B soared — sometimes even topping prices for equivalent space on the Upper East Side. On lower Second Avenue, a 1,200-square-foot two-bedroom apartment was recently put on the market for $2,000 a month. On First Avenue and 1st Street, an 850-square-foot loft rents for $1,200.

“I have people waiting in line to buy co-ops in the East Village, and I have people waiting in line to rent,” says broker Rose Edwards, who’s with the Walscott Company. “These are people who will not even consider another neighborhood. They think they will get a little better value here. They like the feel, the excitement, the diversity. Some buildings in good locations ‘flip’ ownership as many as four or five times over a two-year period, with prices going up 500 percent. You can almost taste it when certain buildings get hot.”

To some of the old immigrants on the Lower East Side, the heat has been too much to handle. In 1951, Maria Pidhorodecky came to New York from the Ukraine on a journey that stopped for several years in a displaced-persons’ camp. In 1957, with savings of $50 and a persuasive goodwill, she took over the Orchidia, an Italian restaurant on Second Avenue. Soon she added some of her own Ukrainian specialties. “Everybody was crazy for my borscht,” says Pidhorodecky, 58. “I cooked my beets. I used fresh vegetables.”

When the neighborhood first began to change, Pidhorodecky did well. The newcomers liked her red cabbage and pirogen as much as the longtime customers did. But today, after 27 years of running the only Italian-Ukrainian restaurant in town, Maria Pidhorodecky is looking for a new place. The Orchidia closed last month when its landlord, Sidney Weisner, raised the rent on her 700-square-foot space from $950 a month to $5,000 — more than 400 percent. “He tells me to raise my prices!” she says. “This is a fourteen-table restaurant. At that rent I would have to charge $50 for a bowl of soup!”

The Orchidia is not alone. Many stores have already been forced out; others face steep increases. “Everyone I know is threatened,” says Barbara Shaum, a leather craftswoman on 7th Street and an activist with the Lower East Side Business & Professional Association. “We are under siege. You go into an area and work real hard and get established and then they want to kick you out.”

Community groups are lobbying before the City Council for a commercial-rent-control bill. Banners reading “Stop the Helmsley Conspiracy” and “Speculators Keep Out” are draped across the streets. Anti-gentrification rallies — some mocking the invading art galleries — are staged. But none of that’s likely to quiet the boom. Tom Pollak, 33, recently arrived from Aspen specifically to buy into the East Village. He has walked every block in the area in search of his first investment. “Ethnic businesses and services will gradually be forced out. Anyone else can be paid to leave,” he says. “If you can get rid of rent-controlled tenants, renovate the place, and charge $700 a month, it’s worth paying them $10,000 or so just to get them out and raise the rents. They’ll all be forced out. They’ll be pushed east to the river and given life preservers. It’s so clear. I wouldn’t have come here if it wasn’t.”

Harry Skydell had few problems getting financing to renovate the Christodora. Citibank agreed to lend the partnership $10 million to develop the building. What’s more, it turned out that the Christodora might qualify for landmark status, which would confer enormous tax advantages. Skydell drew up plans for 77 co-ops in the building, a mixture of studios and one- and two-bedroom units. The penthouse would sell for $150,000. With the rest of the building selling at $160 a square foot, his partnership stood to make millions. “Our goal really was to develop it,” he says. “We had absolutely no intention of flipping it. But by late 1983, unsolicited offers started coming in, one on top of the other. Since there were so many offers, we decided to put it on the market to see what we could get.”

Robert Weiss, the businessman who had been interested in the building the year before, decided to take another look. Early last March, Weiss took his first trip to the top of the Christodora, accompanied by his brother and Harry Skydell. It was a cold and rainy evening. Afterward, Weiss got in his new BMW with his brother and drove past the corner of 6th Street and Avenue B. On a dozen other trips, that corner had been particularly bleak, surrounded as it was by empty lots and burned-out buildings. This time, although it was a weekday, the block was crowded with parked cars. The corner building had been renovated. The Pat Hearn Gallery was open and full of young people. “I didn’t have to go in,” says Weiss. “But I knew this was very East Village. I didn’t know if it was a gallery opening or what — just that it was something new. If there was any hesitation in me about buying the Christodora, that’s when it disappeared.”

Weiss looked at his brother and smiled. “What are we waiting for?” he said. Three weeks later, the Christodora changed hands again. This time, the price was $3 million. In the one year and a week they had owned the property, Harry Skydell and his partners had more than doubled their $1.3-million investment. Since being sold by the city in 1975, the Christodora had increased in price by a factor of 50.

With that kind of inflation, even the new gentry has begun to have mixed feelings about the boom. Some of the so-called pioneers have become infected with a certain nostalgie de la boue. “I much prefer the Puerto Rican families to the secretaries who just moved here and are pissed off that they can’t afford the Upper East Side,” says Patti Astor, of the Fun Gallery. In the old days, ethnic restaurants were unthreatened. Art galleries could find space for almost nothing. Now the art scene has heated up so much that some artists would rather be exhibited in the East Village than in SoHo. “I was offered a much bigger space on Mercer Street for $400,” says Gracie Mansion. “My rent [on 10th Street] is $1,200 — that’s high for less than 800 feet. But I came here because the artistic energy was here and I liked being here better than I liked SoHo.”

Many of the area’s new merchants are struggling as they await the influx of new gentry. Compared with the state of things a few years ago, however, the Lower East Side’s economy is thriving, and a number of the old ethnic establishments — the ones with secure leases — are riding the crest. Since many longtime Lower East Siders live in rent-controlled units, and still others have managed to buy their apartments, the population is far more varied than, say, the Upper West Side’s. And, whatever else, the area is rarely boring. Last week’s performance at 8 BC was called “Lesbian Vampires From Sodom.”

As a place to start out, though, as a magnet for immigrants, the Lower East Side seems to be living on borrowed time. “Manhattan is becoming one big development,” grumbles a Lower East Side merchant. The city owns 206 abandoned buildings in the area and will therefore have a strong voice in shaping the inevitable changes. For now, though, a city spokesman will say only that the buildings ultimately will be returned to the housing market.

Meantime, symptoms of the boomtown fever are popping up in odd places. Last November, Nina Seigenfeld, a co-owner of the New Math Gallery, on 12th Street between Avenues A and B, sprained her back in front of her shop. An ambulance was called, and the attendants prepared to put her on a stretcher. Just then, a hopeful young artist recognized her lying on the sidewalk. Tentatively, he leaned over. “Is now a good time to show you my slides?” he asked.

Today, the Christodora remains as it was when it was sold in 1975, in 1983, and earlier this year — a battered hunk of empty building. Robert Weiss, the current owner, is in the process of negotiating a syndication deal with a “major Wall Street” firm to turn the building into luxury rental units. Technically, though, it’s on the market. Early this month, George Jaffee, the Brooklyn developer who had bought it nine years ago for $62,500, got a phone call from a broker. The broker had a property on Tompkins Square Park he was trying to sell. To Jaffee, the building sounded familiar. He had to smile. This time around he could pick up the Christodora for just $3,500,000.