Who Would Marry Robert Durst? Debrah Charatan’s Untold Story

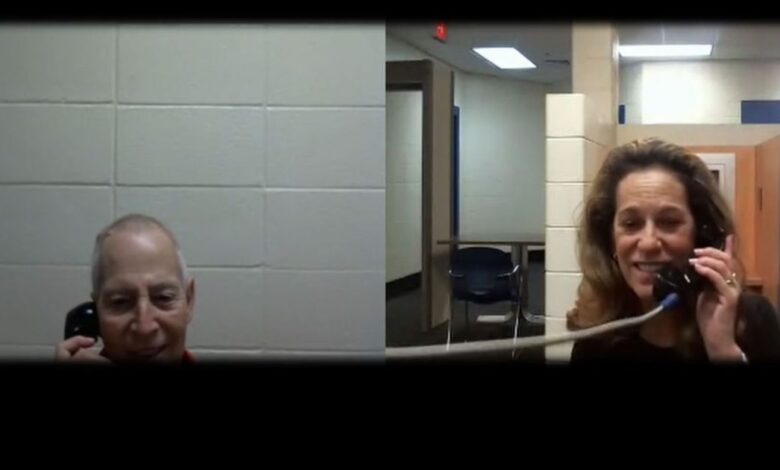

Robert Durst and Debrah Charatan as seen during a visitation featured in The Jinx.

Photo: Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office

On a gray November afternoon in 2001, Robert Durst was handcuffed outside a grocery store in Pennsylvania. A security guard had caught him trying to steal a chicken sandwich, ending a nationwide manhunt that had gone on for seven weeks. On paper, Durst had plenty of money — in fact he was an heir to one of the largest real-estate fortunes in Manhattan — but he wanted to test the limits of what he could get away with. “I decided rather than to pay, I was just gonna take it,” he said.

Durst had been living in Galveston, Texas, renting a cheap apartment in a fourplex, where he’d become friendly with Morris Black, his 71-year-old neighbor. The pair spent their days together at the library, reading the news, and many of their evenings at a dive bar, where Durst, who was 58, usually paid for the drinks. When the older man realized who Durst was, he allegedly tried to blackmail him. On September 30, garbage bags containing Black’s body parts washed up in Galveston Bay. Durst was charged with murder; the case went to trial in 2003.

That story may be well known to some readers. Durst has long been a subject of fascination for true-crime audiences all over the world. HBO’s 2015 documentary series The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, in which he sat down for 21 hours’ worth of interviews, made him almost a household name and eventually led to his being sentenced to life in prison.

But one moment that followed the arrest in Pennsylvania may be less familiar. When police searched Durst’s car that day, they found envelopes full of cash, two handguns, and a pen with the words “Debrah Lee Charatan Realty Inc.” printed on the side. There was also a notebook where Durst had scrawled four phone numbers where Charatan could be reached.

Charatan had long been known as Durst’s friend and confidante. But following his arrest, the public learned that she was also his wife — they had gotten married in December 2000. (Through her lawyers, Charatan declined to comment for this story.)

For the next 20 years, until his death in 2022, Charatan would stand by Durst. She paid his bills and oversaw his investments, she helped coordinate the defense for his various trials, and she called and visited regularly whenever he was locked up. And yet, for as much as her husband’s life story and psychology have been probed, Charatan herself remains a mystery. The New York Post, in its inimitable way, captured the obvious question in a headline: “Who the Hell Would Marry Robert Durst?”

Charatan came to my attention when I was working as an investigative researcher on The Jinx: Part II, which aired in 2024. One of my tasks was to dig into her past — from her hardscrabble childhood to her recent business dealings. Only a small portion of what I and the film’s producers managed to uncover was included in the series, but the portrait of her that emerged was of a woman with a great deal of control over Durst and his money.

With the Durst fortune at her disposal, Charatan was able to transform herself from a real-estate broker into an investor, making tens of millions of dollars buying and selling properties. Now that he has died, she stands to inherit tens of millions more from her husband’s trust. But there’s a problem: That inheritance is currently tied up in litigation brought by the siblings of Durst’s first wife, Kathie McCormack Durst, who died under suspicious circumstances in 1982.

Kathie’s family believes Durst murdered her, and its members are suing for wrongful death, arguing that they are entitled to what remains of his estate. They have also charged that Durst and Charatan schemed to hide a portion of his money so it would be shielded if such a suit were ever filed. Robert Abrams, the McCormacks’ attorney, has asked the courts to block Charatan from inheriting Durst’s trust — which contains some $36 million — and to investigate what happened to the rest of his fortune, which, at one time, totaled around $100 million. “Our ultimate goal is to claw back all the money she gained from Durst and invade the trust,” said Abrams. “If we’re successful, she walks away with no money.” A ruling could come as early as this month.

Charatan at a charity luncheon in 2014 in Sagaponack, New York.

Photo: Mike Pont

Charatan’s first brush with fame came in April 1984, when she was featured in an issue of Savvy: The Magazine for Executive Women. In a photograph, she leaned on the hood of her brand-new white Corvette with the Manhattan skyline behind her, wearing a topcoat and boots and smiling stiffly at the camera. The headline read, “The Millionaires: Making It Big by Age 35.” Of the four women being profiled, Charatan, at 27, was the youngest.

“I’ve loved money since I was 5 years old,” she told the reporter. Her background was humble: She grew up in Howard Beach, a working-class neighborhood in Queens, near JFK. Her parents were Polish immigrants, and her father, who ran a kosher butcher shop, had lost a leg to a land mine. “You don’t necessarily choose a mate with one leg,” Charatan said in another interview. “They tolerated one another. There wasn’t lots of love.”

After high school, Charatan went directly to Manhattan, first working as a secretary in a real-estate firm and later starting her own brokerage with a $2,000 loan and a basement office near Madison Avenue. The market was booming in those years, and she was so successful that by the time of the Savvy profile, she had 17 salespeople working under her, all of them women. She said the firm, Bach Realty (pronounced Baysh), had sold $150 million worth of property in 1983.

Like another real-estate figure who grew up in outer Queens, Charatan was given to garish displays of wealth. “How many gold watches can you use?” she asked. “I have Piaget, Concord, Cartier. How many $400 silk blouses can you wear? How many $750 suits?’”

But, as it would turn out, the Savvy story represented the zenith of her early career. In 1985, her life started falling apart. That year, Charatan began an “intensive psychotherapeutic relationship,” per state records, with a Manhattan psychiatrist named Isaac “Ike” Herschkopf.

Recently, Herschkopf’s name has become infamous; he was the focus of the 2019 podcast The Shrink Next Door, and he was later portrayed by Paul Rudd in the Apple TV+ miniseries of the same name. But for all of Herschkopf’s media exposure, his relationship to Charatan and his connection to the Durst saga have never fully been revealed. She would spend 18 years as his client, and it would dramatically change her life in every way.

The podcast and TV show tell the story of Marty Markowitz, a client who started treatment with Herschkopf in 1981. Some of Markowitz’s experiences resonate strongly with Charatan’s biography. Early in his treatment, for instance, at the doctor’s urging, Markowitz severed all contact with his family members, including his sister, who worked with him at the family’s fabrics company.

Charatan’s experience is also outlined in the 2019 podcast, though she appears under a pseudonym. She says she started seeing Herschkopf at a difficult time in her life and credits him with guiding her through her divorce. Shortly before Labor Day, in 1985, Charatan left her then-husband, taking her 17-month-old son with her. “He taught me how to control my emotions so I could make better decisions,” she said about Herschkopf. “In some ways he taught me how to protect myself.”

The doctor also pushed her to cut herself off from people close to her. Former employees told Newsday she even fired her mother from her position at Bach (though Charatan claimed her mother left voluntarily). Her behavior at work became ever more draconian. In 1986, she fired most of her employees en masse. “A shark is a kind word for her,” one former employee told me.

Many people have said Herschkopf’s patients were devoted to him in a way they found unsettling. “I always felt like all the people that went to see him — they were like this cult,” one former employee of Charatan’s said. “She was like one of the followers of Charles Manson,” another former acquaintance said.

A former friend who knew Charatan while she was seeing Herschkopf remembers her being secretive about the relationship. Whenever she had an appointment with the doctor, she put a dot on the calendar instead of writing his name. But the friend suspects Herschkopf played a major role in the rupture at Bach. She remembers a comment Charatan made in the aftermath: “Somebody very wise once said to me, ‘When you cut your top people, another person will rise, so you don’t have to worry about it.’” The New York Department of Health later determined that besides treating Charatan as a patient, he acted as her business consultant. (Herschkopf didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story.)

As Bach Realty fell apart, Charatan and her husband finalized their divorce. Midway through the proceedings, she stopped fighting for custody of her son and agreed to let her husband raise him alone. Eventually, Charatan would rewrite her will to exclude her family and make Herschkopf’s daughters the sole beneficiaries.

Durst entered Charatan’s life in 1988, when they met at a real-estate function. Nick Chavin, a close friend of Durst’s who was also at the party, recalled later how Charatan had nudged him to introduce them. It was six years after Kathie Durst’s disappearance.

Charatan was at a low point. Legal fees and payouts to her former employees had bankrupted her, and she’d been reduced to driving a Ford Taurus. As for Durst, he was flush with money from the family trust. “He’s funny, he’s very bright, he was very kind, we had a lot of fun together, and I saw him as a successful businessman,” she said in 2023, when she was asked about the early days of their relationship. She, in turn, could be very charming when she wanted to be. “He definitely pursued me,” Charatan said.

In 1990, they moved in together, renting an apartment on Fifth Avenue — where she had long dreamed of living. Durst also helped restore other luxuries she had lost. “When I met her, she was still buying Hanes pantyhose,” one former friend recalled. “All of a sudden she was buying from Wolford.” She started driving an Infiniti, and later she bought a home in Bridgehampton.

The couple bickered constantly, and Charatan didn’t like Durst’s heavy drinking or his pot smoking. She moved out after a year and a half. But they remained close, if only as friends. Durst split with his family in 1994, after his father named his younger brother the president of their real-estate company. He left New York and started roaming among homes he owned in Houston, Dallas, rural Northern California, and Connecticut. During these years, he severed ties with most of his acquaintances — but not Charatan. By this point, she’d been his main confidante for years.

The couple went on trips to Amsterdam, Japan, Paris, Vermont, and a tennis camp in Florida. And in 1998, Durst started spending more time in the city again, “with my only friend Debbie,” as he would later write. They would meet for dinner, go to the movies, and take runs in Central Park. When Charatan ran the New York City Marathon, Durst took the subway and met her every three miles.

In 2000, Durst received some upsetting news: the Westchester County district attorney’s office had reopened the investigation into Kathie’s death. As he made preparations to go on the lam, he needed someone to receive his mail and manage his affairs — and Charatan was the obvious choice. “I had to have someone write my checks,” Durst would later tell his sister. “I was setting myself up to be a fugitive.”

Durst also redrafted his will to make Charatan the beneficiary, an echo of her experience with Herschkopf. But given that his wealth was bound up in the family trust, with tight restrictions on how it could be disbursed, the only way for her to inherit the money was for the two of them to marry.

The wedding happened that December in a conference room on the 25th floor of Times Square Plaza. After it was finished, the couple did not take photos, nor did they spend their wedding night together. However, that same day, Durst updated their legal arrangement. He had already given Charatan power of attorney, but now he added a clause that gave her authority to make gifts from his estate to herself and to companies she owned — effectively signing over control of his fortune.

As Christmas approached that year, Durst had another matter to resolve: There was a second woman in his life who also knew many of his secrets. Her name was Susan Berman, and she lived in Beverly Hills. The two of them had been close since they attended UCLA together in the 1960s. Lately, Berman had been hard up for money, and she had told Durst (evidently, according to prosecutors, meaning to extort him) that she’d been contacted by the Westchester DA’s office. They wanted to interview her about Kathie’s disappearance — and Durst later said she was planning to speak with them.

There was no love lost between Berman and Charatan. “Debrah hated Susan,” said Terry Chavin, Nick Chavin’s wife and a former Bach employee, during a 2015 call with investigators. “They fucking hated each other.”

On the afternoon of December 24, police found Berman lying face-up inside her house in Beverly Hills with a pool of blood around her head. She had been fatally shot. Durst was almost immediately seen as a suspect. He had flown to California several days before the murder, but when investigators questioned him, he claimed he’d spent that time visiting a friend in the northern part of the state, hundreds of miles from Los Angeles. Later, he also testified that by Christmas Eve, he was back in the Hamptons with Charatan.

Durst was never able to present proof that he was in the Hamptons on Christmas Eve. But Terry Chavin told investigators that a week before the murder, Charatan asked her to come over to her house on Christmas Day. Chavin thought the suggestion was odd. “Debrah’s Jewish. I’m Catholic. I have a big Catholic family,” she said in 2015. “Like, ‘Debrah, come on. You don’t even have a fucking Christmas tree. Are you kidding me?’” Chavin says she didn’t make any promises.

On the 25th, Chavin stayed home. And on the 26th, she received a voice-mail message that she later described as “hysterical.” Charatan was furious that she hadn’t come. “I played it for my friend,” Chavin later said. “But, like, we can’t understand why she’s so upset.” The whole experience, she said, was “really weird.” In a deposition, Charatan said she had no memory of inviting Chavin to her house, calling Chavin “an angry liar.”

Durst spent the next year hiding out in Galveston, while Charatan stayed in New York. It was in the fall of 2001, nine months after Berman’s death, that he killed Morris Black. Charatan has said she was “shocked” and “horrified” when she learned what he’d done.

She made these remarks in a 2023 deposition, and it’s worth quoting them in full, because it’s likely the only instance where she has spoken on the record about her husband’s violent side.

“Did you ever consider that perhaps you didn’t want to be married to someone who’s cutting up a dead body like that?” asked Matthew Capozzoli, the attorney deposing her.

“I thought about it.”

“And what did you conclude?”

“Well, I knew a different Bob Durst than you do, and obviously, you know, somebody who can do these things, you might say they are sick. And I just felt like I didn’t want to desert him.”

“Did you think he was sick?” Cappozzoli pressed.

“Well, something.”

“Did you have any idea what that something may have been?”

“Well, something’s off.”

These concerns, however, didn’t stop her from intervening to get Durst out of the Galveston jail. As soon as his bail was set, Charatan wired him $300,000, and he immediately fled town. Several days later, she tried to withdraw more than $1.8 million from his bank account, presenting her marriage license to show she was authorized. But the account had already been frozen and investigators were alerted. The police, and then the press, learned about their marriage for the first time.

Durst was charged in Texas with murder. His family moved swiftly, hiring a team of high-profile defense lawyers. But Charatan had different ideas about how the defense should be managed. She was still seeing Herschkopf in these years, and as criminal proceedings against her husband moved forward, he coached both of them on how to deal with the case.

Shortly after the arrest, Herschkopf went to visit him. It’s unclear how much Durst knew about the doctor, but based on his comments after the meeting, it seems this was the first time they had spoken directly. “He must be the smartest person in the world,” Durst told Charatan later. He also said Herschkopf had urged him not to have a psychiatric evaluation done. “I am absolutely convinced that he is absolutely right,” Durst said. “He is right,” Charatan replied.

As the trial approached, the family’s lawyers planned to make an insanity defense, but Charatan rejected this idea. If Durst were found incompetent, he stood to lose control over his share of the family trust. (Herschkopf also had something to lose here. Since his own family was written into Charatan’s will, he had a stake in seeing her inherit the Durst fortune.)

In the end, Durst fired one of the attorneys his family had hired and selected another who was more amenable to Charatan. The lawyers dropped their plans for an insanity defense and decided instead to argue that Durst had killed Morris Black in self-defense. The strategy paid off: In November 2003, a Galveston jury acquitted Durst.

Charatan was not present for the verdict, but Durst called her as soon as he was back in his cell. “All I’ve thought of is being able to see Debbie on the outside,” Durst told the New York Post. “She’s what’s kept me alive. All I want to treat myself to right now is seeing Debbie.”

Herschkopf’s intervention in the trial turned out to be his swan song in their doctor-client relationship. In 2003, the same year as the acquittal, Charatan ended their arrangement. “I felt like Ike wasn’t being honest with me,” she has said, “and I felt like I outgrew him.” She told Joe Nocera, the writer of The Shrink Next Door, that she had wanted to leave earlier, but she held off out of concern that Herschkopf would be hurt. She considered buying him an expensive gift as a consolation. “That’s how brainwashed I was.”

According to Markowitz, Herschkopf’s former patient, after Charatan broke off contact, she altered her will once more, removing the doctor’s family as beneficiaries. She also made two other significant life changes. By 2004, she was in a relationship with Steve Holm, a real-estate attorney whom she had known at least as far back as the 1980s. By all accounts, the two of them were deeply in love. Charatan even considered divorcing Durst so she could marry Holm, though this would have legally barred her from inheriting Durst’s money. “I asked Steve what he wanted me to do, if it mattered to him,” she said in the 2023 deposition. “If it mattered to him, I would do it.” Ultimately, they agreed she would stay married to Durst. But she considered herself Holm’s wife, and many people in their synagogue reportedly thought she was. She and Holm created a charitable foundation, which made donations to the Museum of Modern Art, Chabad of Southampton, and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation.

In 2008, she launched a new business enterprise, naming it BCB Property Management — after her son, Bennat Charatan Berger, with whom she had reconnected. “I created the company in the hope that he would become part of it,” she explained in the deposition. In this new venture, instead of merely brokering sales, Charatan reinvented herself as an investor. Between 2008 and 2015, LLCs registered at her business address purchased hundreds of millions of dollars worth of property. Exactly where she acquired the capital for all the down payments is a matter of some controversy — but it’s clear that at least a portion of it came from Bob Durst’s fortune.

To understand why she’s been cagey about this, it helps to go back to some of the conversations between her and Durst that have been recorded during his various jail stints. As far back as 2001, they both knew there was a possibility that Kathie’s family would sue him for wrongful death and try to seize a portion of his assets. While Charatan was careful about what she would say over a recorded line, Durst spoke openly about schemes to shield his money from the McCormacks.

“The question is,” he said in a 2001 call, “can we do something to hide it from the wrongful-death lawsuit?” On another call, several weeks later, he said his attorneys had given him advice about this, and he was convinced the best way was for Charatan to start buying real estate. “What immediately goes through my mind is that you buy something, get the biggest mortgage in the world on it, and pay the mortgage charges with my money.”

If these investments turned a profit, so much the better; but the way Durst spoke about it, that was not the main purpose. Rather, it was a mechanism for putting distance between the money and himself. “Any way we can transfer money to you,” he said, “and out of my estate, is brilliant.”

It took several more years before the two of them gained full control over Durst’s share of the family fortune. In 2006, with the help of an attorney Charatan had met through Herschkopf, they reached a deal with the family that allowed Durst to walk away with $67.5 million. Charatan incorporated her new business — and started her buying spree — not long afterward.

With most of the property purchases in question, it’s hard to say for sure whether Durst’s money was being used. But in some cases there is hard evidence linking him to the transactions. As of 2022, Durst’s trust had a stake in at least 12 buildings that were purchased by LLCs linked to Charatan.

Most of these investment properties tied to Charatan’s company are residential, and they’re spread across the city. Several are in Williamsburg, including a cluster of apartment buildings just north of the Williamsburg Bridge, with more than 100 units between them. Others are in Harlem, Kips Bay, the East Village, and Windsor Terrace.

Charatan and Berger, her son, also became drivers of the gentrification of Crown Heights. Berger joined the company in 2011, as his mother had hoped; but before that, he spent a year working at Kushner Companies — with the family of Jared Kushner. The Kushners are notorious for buying rent-stabilized apartments and converting them to market-rate units.

After Berger joined BCB, the company used a similar playbook, especially in Crown Heights. Between 2012 and 2014, companies registered at BCB’s address purchased roughly a dozen buildings in the neighborhood. BCB launched an aggressive campaign to remove longtime tenants so it could raise the rents. In some cases, it offered buyouts ranging at least as high as $70,000. Many of the tenants who declined, preferring to stay in their apartments, soon found that basic maintenance needs were being neglected. Meanwhile, tenants also started to feel like they were living in construction zones as empty apartments around them were being gut renovated. In some cases, the spruced-up units were later rented out for more than twice what the rent-stabilized tenants were paying.

In 2015, less than 24 hours before the finale of The Jinx was released, Durst was arrested for what would turn out to be the last time. Two days later, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s charged him with Susan Berman’s murder.

With the arrest came more unflattering press for Charatan — along with the prospect that she herself might face criminal charges for the support she’d given him over the years. In March 2015, the Post reported that prosecutors were building a case against her personally on the grounds that she’d helped her husband try to evade arrest. “The wife is definitely in play,” an anonymous source told the paper. It was presented as a ploy to get her to testify.

The Post’s reporting was not necessarily trustworthy. The paper also claimed that before his arrest, Durst had planned to flee to Cuba — which was true — and that Charatan intended to go live there with him — which was not. Even so, the notion that prosecutors were preparing to charge her seemed realistic. Charatan was concerned enough that she hired a high-powered criminal-defense lawyer, Alan Abramson, who has also represented Alec Baldwin (Abramson didn’t respond to a request for comment for this story).

She offset the attorney fees with her real-estate profits. In the fall of 2014, BCB and the companies associated with it had started selling off many of the properties they’d acquired. At the end of 2015, Durst’s accountant noted that $4.1 million had been spent that year on legal fees, but Charatan had made $4.2 million on property sales — “so she covered that with her real-estate profits.”

In the end, however, she was never charged with even a misdemeanor, nor was she pressed to serve as a witness. It’s worth looking at how this played out.

The lead prosecutor assigned to the case was John Lewin, a burly 60-year-old who has been dubbed “the king of cold cases” by Los Angeles magazine. Lewin apparently grew close to Alan Abramson in the course of the litigation. One person who knows Lewin described his attitude as a “full-on man crush.” (As for Abramson, when he was asked in a deposition whether he had ever called Lewin a close friend, he answered, “I do not believe so.”)

They first became acquainted in or around 2015, when Lewin got in touch about interviewing Charatan. “I contacted Alan,” he recalled in the deposition. “Had never met him before. Immediately, first time on the phone I liked him.” They agreed Charatan would come out to Los Angeles so Lewin could speak with her. But the sole purpose, Lewin has said, was to show her the evidence he’d compiled against her husband in hopes that she’d persuade him to plead guilty. “She’s not a target,” he said, describing his thinking at the time. “She’s not somebody that has committed any crime.” (Lewin did not respond to a request for comment on this story.)

As early as the summer of 2015, Lewin was also recorded saying he saw no reason to charge Charatan with a crime. “Debrah’s a lot of things, from what I can tell,” he told Terry Chavin. “I don’t have any evidence that Debrah is involved in killing anybody.”

At the same time, over the course of the litigation, Lewin himself has presented evidence of actions by Charatan — not directly related to the murders — that could rise to the level of criminal complicity. He said in court in 2021 that she’d given Durst “assistance while he eluded authorities.” She also helped Durst make payments to at least one witness, which some prosecutors might consider a form of bribery. Robert Abrams, the McCormacks’ attorney, argues that under these conditions, a normal prosecutor would have charged her and offered her a deal to testify. “I would say that’s a prosecutorial copout,” he said.

In fairness, it’s possible Lewin made this decision on strategic grounds. Perhaps he thought there was more to gain by treating Charatan as an ally than an adversary. However, when I called Lewin, he refused to discuss anything involving Charatan or her lawyer. “That’s just — you know, people want salacious information,” he said. “It’s not what I do.”

Durst’s final trial ran through the summer of 2021. Abramson was in attendance every day, and in the evenings, he and Lewin sometimes met for dinner. In September, the jurors voted to convict Durst in the murder of Susan Berman. And the following month, the judge sentenced him to life in prison.

However, the friendships Lewin had formed outlasted the trial. In the summer of 2022, the prosecutor and his daughter took a trip out east. They visited New York City, then spent two nights with Charatan at her beachfront mansion in Bridgehampton. As Lewin explained in his deposition, Abramson arranged the visit, and it was Lewin’s understanding that Abramson would be there, but he never showed.

Lewin has insisted there was nothing inappropriate about this visit. After all, the case against Durst was over. Abrams, the McCormacks’ attorney, sees it differently. “The appearance is that whatever he did, he did because of his friendship with Charatan,” he said. “Whether it’s true or not, that’s the appearance. Lawyers are supposed to avoid the appearance of impropriety.” The Los Angeles county attorney’s office has said that it is aware of the situation but told New York that it “does not comment on personnel matters.”

Robert Durst died only three months after his sentencing. His health had been poor for some time, and in early 2022, he had a heart attack. Charatan arranged a small service for him at her apartment in Manhattan, inviting attorneys and other acquaintances — “people that really knew him.” Later, she scattered his ashes off the coast of Long Island, near Bridgehampton. “He loved it there,” she said.

Of course, his death represented more than the loss of someone close to her: It also meant she was one step closer to inheriting his money.

In terms of financial resources, the McCormack family is far outmatched, but over the past ten years, Abrams has mounted a dogged campaign on their behalf. He has filed litigation in three separate venues: the wrongful-death claim in federal court; a suit in Westchester County’s surrogate court, where he and his colleagues are seeking to pry into the trust and see exactly how the money has been spent; and a suit in Texas, aiming to have Charatan removed as the executor of the estate.

“Each of these cases is a building block,” Abrams said. Besides winning a verdict or settlement for the family, Abrams wants to further expose how Charatan and others in Durst’s orbit supported him while he was committing crimes and avoiding conviction. “We are not stopping until the prosecutors in New York and California recognize that the individuals who helped Durst cover up this murder are held criminally responsible for what they did,” he said. “I know it’s a stretch, but we’re just not stopping.”

Even if criminal charges never materialize, it’s not hard to imagine the McCormacks winning their civil cases and gaining access to some or all of the $36 million in Durst’s trust. To secure a judgment in their favor, they only need to show that it’s likely that Durst killed their family member — they don’t need to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. Abrams is hopeful on this count, because even Durst’s family members now say they believe he’s guilty.

Charatan, who now spends much of her time at a home she owns in the Miami area, has declined to settle, and in private conversations, she’s been adamant that she’s not simply holding out as a legal strategy; rather, she’s truly determined not to give the McCormacks anything.

Charatan has endured a lot to get where she is: the clandestine wedding, the overnight flights to Galveston, the hundreds of calls from jail, the fending off of reporters, the fights with her husband’s family and his lawyers, the years’ worth of suspense surrounding his trials. In many ways, her life has revolved around Durst since the two of them first met in 1988. From that perspective, it’s easy to see how, in her mind, she has earned the inheritance.

She said as much in the fall of 2023, when she sat for the deposition with Abrams and one of his colleagues. Abrams asked whether she believed others had used Durst for his money. “Plenty of people,” she replied.

“You got money from Durst, didn’t you?”

“I did.”

“How are you different?” he asked.

“I didn’t need it.”

“Did you feel like you deserved it?”

“Absolutely.”

“Why?”

“He was my husband.”