The COVID Memorial Project: Hector’s Tribute

A year after New York City was shut down, COVID-19 has claimed the lives of more than 30,000 of its residents. The scale of the tragedy made it difficult to understand the private sorrows many of us have experienced: the million sorrows of lost friends, lost livelihoods, lost neighborhood accessories, a sense of belonging. lost. Instead of offering a large, permanent memorial, we asked a wide range of New Yorkers about the moments of the pandemic that marked them and how they would like those experiences to be remembered. In response, a selection of architects and artists translated these memories into proposals for temporary installations. We imposed no budget limits and no restrictions: the result could be a sculpture, a mural, a pavilion, a song – anything that could be part of the streetscape for a while. Here is one of 15 concepts submitted by architects, designers, artists and composers.

A disability rights activist, board member Independence Center for People with Disabilities, founder of United for Equal Access, and longtime New Yorker.

I live in the Bronx and am a disability rights activist, practically trying to ensure that people with disabilities have access to everything in New York City, be it transportation, fair housing, etc. I am 32 years old and have been using a manual wheelchair for ten years now. It has become more difficult for me to travel because I don’t have an elevator station. So normally wherever I had to go in Manhattan I had to take the BX19 [bus] about a mile and go to Hunts Point and use this station to come back to go to Manhattan. Frankly, this whole pandemic, I took the train once. There is a fear of getting on the train because there has been a series of unprovoked attacks. Unfortunately, some of these [attackers] are mentally disturbed, and I know they attack a lot of people of Asian descent, but at the same time, they might see me, as a wheelchair user, as a target. So it strengthened my sense of awareness and I didn’t really want to get on the metro as well.

I feel like a soldier left all alone in the middle of nowhere. You have lost all of your comrades, you have tried to do your best, but you are just the last man standing and you are all alone and the fight is not even over yet. I’m this one man army trying to survive, trying not to get this COVID, but also trying to see what comes next, to get back to some kind of normalcy, to get out of this war. It’s a dark and lonely place, you know? I wish I could throw some kind of party for my birthday [in May]. I just wish I could go back to normal, even if I have to wear a mask for a few more months, but at least go back to work and go back to the gym and see people, go sit in a restaurant and eat – stuff like that.

My stepdad died because he got caught up with all the Andrew Cuomo bullshit. He was in a retirement home. He caught COVID. They sent him to the hospital. They never told us. And then they sent him back to the nursing home. Then it got worse. Then they sent him back to the hospital. It was only then that the hospital contacted us and said, “Hey, he’s been here for a few days. And we just found out who he is. Because they had him as a stranger. My mother spoke to him the day before he died. He seemed to agree 100%. They did not allow us to see the body. They didn’t take any pictures, nothing we asked for – we weren’t even allowed to have a funeral because they lied to us. They just gave us an urn [filled] with what they say is his body. But he died alone. I don’t even know if he was in a good mood. Not having a clue what his last glances were bothers me a bit. My stepfather practiced the Rastafarian tradition. So we were going to put him in an emperor’s outfit. We were going to give him nice clothes and it would be just us and his only brother, no friends or nothing. And they took all of that away from us.

“Before the pandemic, I was never in the house,” says Dustin Jones, a disability rights advocate who is currently involved in class actions against the MTA linked to the shortage of elevators or ways without stairs in the metro. He was busy traveling to Albany to attend various court hearings, going to his office in Union Square and living his life. But during the pandemic, all of that disappeared overnight. The isolation Jones has devoted his life to combat has returned to him. Before the pandemic, traveling around the city was already difficult for Jones. But cuts in MTA service and fear of COVID transmission and unprovoked attacks on trains meant he no longer felt safe on the subway. “There was a nothingness routine and it started to bother me because I was so used to going here, going there,” Jones says. “It still bothers me now.”

Jae Shin and Damon Rich, partners at Hector, the practice of urban design and civic arts behind a new waterfront master plan for Newark and a redesign of Mifflin Square Park in South Philly, knew they wanted to create something for Jones that would honor his advocacy work and bring him something joyful. As designers with extensive experience in democratic, community-driven design processes, they also wanted to introduce a new kind of public space.

To that end, Hector designed “The Curb Cut Party,” a scenographic celebration space that Jones could use for his birthday and to give his stepfather the come home he and his family wanted. It is filled with “monumental party furniture” in the form of an accessible elevator, which could contain a DJ booth, a raised ramp that could be used as a stage, and a sidewalk that could be used as a chill out space at the party. The concept highlights the things Jones fights for and presents them as things we should all become more aware of.

“We hope it highlights how every sidewalk, ramp and subway elevator in New York City is a testament to all the work that goes into making the environment more responsible to all residents,” Shin says. “And we hope this monument provides the liberation and relaxation of this era that Dustin deserves.”

Art: Hector

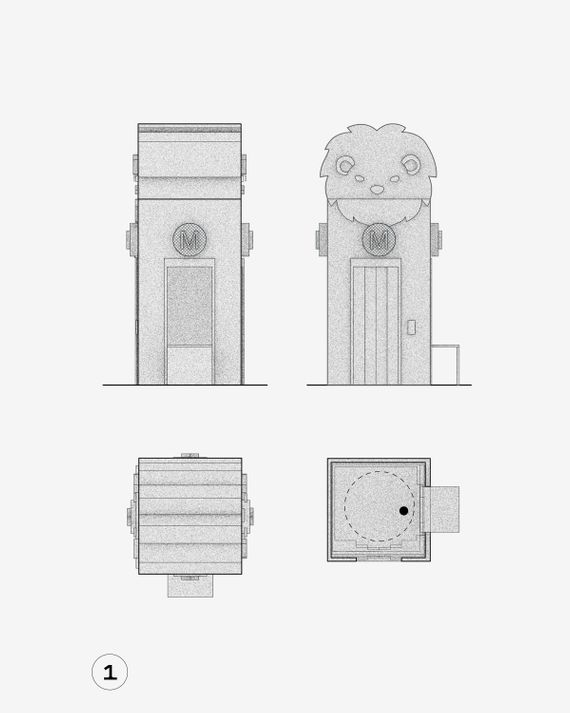

Jones’ advocacy work is currently focused on the accessibility of MTA stations. Currently, only a quarter of the city’s 472 metro stations are accessible. Elevators are essential parts of this work. Hector plans to build a DJ booth with the exact details of a full-scale, ADA-compliant elevator entrance – one with doors on both sides, buttons at the correct height – in order to show more people what they look like and what Jones is fighting for.

Art: Hector

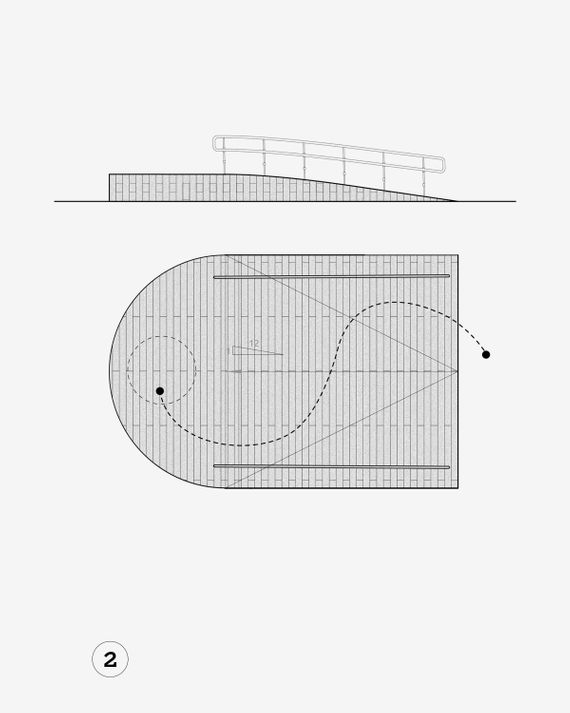

Hector envisions a stage for the party in the form of a huge ramp, with the right slope needed for wheelchair users. (It might surprise many people to learn that some of the ramps at MTA stations are not actually wheelchair accessible because the slope is too steep.)

Jones brought up ambitions to run for office, and Hector imagines it as a space where he could deliver a speech someday. While it is not uncommon to find stages and amphitheatres in New York City parks – as in Poe Park, Prospect Park, and East River Park – they might not be fully accessible either.

“If we design and build more responsible cities for more people, we could have a city that is much more interesting and fair to ourselves,” Shin says. “This job is not necessarily this big abstract thing. Liability could mean that a park is designed for people who live nearby. “

Art: Hector

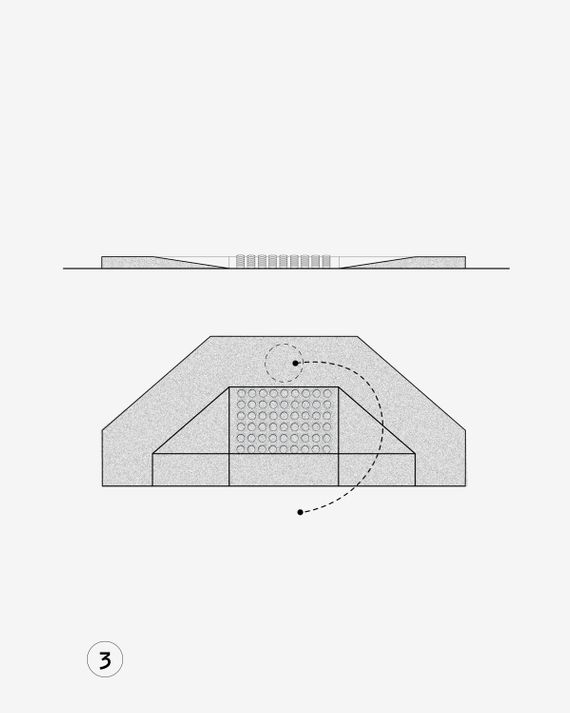

At many intersections in the city, if well designed, there is a gentle slope where the sidewalk passes to the roadway. It’s called a “sidewalk,” and if you’ve pushed a stroller or rolled up a suitcase you’ve probably noticed how useful they are and how frustrating it is when they’re not around. Their existence is the result of decades of work by disability advocates like Dustin Jones, who fought for equal access in cities. If you are a wheelchair user like Jones, a curb isn’t about remedying an inconvenience, it’s about civil rights. Hector’s concept envisions the sidewalk becoming a party space where people could take a break from dancing, have calmer conversations, or just watch people.

“The sidewalk as an architectural artifact is perhaps more meaningful to us than the pyramids in terms of what it says about our ability to create a shared living environment for the people who live here,” says Rich.