That Cardboard Bed Was Supposed to Be a Utopia

Photo: Clockwise from top left: Toomey & Co. Auctioneers, Alamy Stock Photo, Manuel Kretzer / Responsive Design Studio, Alexandra Lange

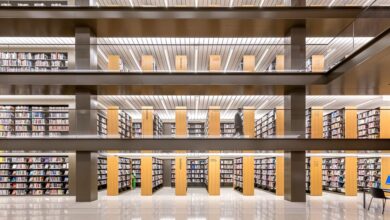

Yes, you can have athletic sex in a cardboard bed. Rumor that the cursed COVID Olympics in Tokyo promoted celibacy through flimsy furniture has since been debunked, but that doesn’t mean these beds don’t deserve a closer look. It is not their material that is weak, but the design ambition behind them. The sleek temporary architecture has been a feature of the Olympics past – just look at Los Angeles in 1984, where construction scaffolding become enchanting Pop villages – but these square pieces of furniture read as designed to be forgotten, and not designed to give stressed bodies the best rest.

Why build another box when since the 1960s cardboard dreamers have demonstrated that the material can bend, curl and roll, much like Irish gymnast Rhys McClenaghan, who went viral on Twitter by jumping on one of these beds to refute his anti-sex reputation? Why build something in white or brown when they could be red, yellow, or blue or have peas or Olympic rings?

Despite its reputation, this cardboard bed in the Olympic Village in Tokyo is sturdy enough for two.

Photo: Kiyoshi Ota / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Once upon a time, the cardboard was going to save us all from conformism. “These beds are pretty basic,” says Andrew Blauvelt, director of the Cranbrook Art Museum and curator of the 2015-2016 Walker Art Center exhibition. Hippie modernism, which featured some of the strangest and craziest experiences in the temporary living environments of the 1960s. “The Olympic Village does it for ecological reasons, and that’s what’s funny. Stuff from the 1960s was meant to reflect a new modern lifestyle – it was meant to last longer rather than just being thrown away after use. Cardboard gained attention at the time because of its ubiquity as a by-product and then as a design problem generated by post-war consumer culture. Cardboard was lightweight, portable, and suitable for DIY and customization. Giving boxes a second life at home was a positive adjustment to the throwaway culture.

It was also seen as a material for play, an invitation to creativity. No less an eminence than Dr Spock recommended cardboard box as an alternative to expensive ready-made toys. A group known as Adaptive Design Associates develops custom cardboard furniture for people with disabilities and then modifies it, sometimes over the years; as Sara Hendren wrote about organizational designs in her book What can a body do?, they are strong enough to be “temporary, but also temporary to permanent, for years if necessary… Cardboard has the virtue of being temporary, and it retains its experimental spirit even if it offers its robustness.

Ken Isaacs, Cranbrook graduate and author of the 1974 book How to build your own life structures, embodied this philosophy, according to Blauvelt. “His whole idea was that you just give the blueprints and drawings” – in Isaacs case for a wood-frame living unit called the Super Chair – “and then you can make it as elaborate as you want.”

Frank Gehry is one of the designers who appropriates the experimental spirit of cardboard. He started playing with the material when asked to design a quick and inexpensive environment for a symposium to be held at artist Robert Irwin’s studio in 1969. He continued to play thereafter, deciding ultimately he preferred a side view that showed the ripple corduroy. By laminating several sheets, he was able to create an openwork weaving board, lighter than wood but almost as strong, and he used them to make a filing cabinet and desk for his desk.

As critic Paul Goldberger wrote in his biography of Gehry, “The office became the reception desk for his office, where it would be an immediate signal to visitors that this was not the kind of architectural office outfitted with the sleek Knoll and Herman Miller furniture you’ve seen everywhere else. Just like the chain – The fences at Gehry’s house in Santa Monica indicated that it wasn’t like the other bungalows.

His Rocking chair, which looks like a doodle carved from a block of ripples, ended up being part of a furniture collection featured in the Los Angeles Times in 1972 under the title “Why Didn’t Someone Not Think About It Before?” For its cheap price (a table costs $ 100) and sturdiness (said table can support 100 pounds). The line became known as Easy Edges. Several pieces are still in production and available, Dear.

Clockwise from left: Gehry’s Wiggle chair. Photo: Arcaid Images / Alamy Stock PhotoThe Chick ‘n’ Egg chair. Photo: Manuel Kretzer / Responsive Design StudioToobs beds. Photo: Toomey & Co. Auctioneers /

Clockwise from left: Gehry’s Wiggle chair. Photo: Arcaid Images / Alamy Stock PhotoToobs beds. Photo: Toomey & Co. Auctioneers / …

Clockwise from left: Gehry’s Wiggle chair. Photo: Arcaid Images / Alamy Stock PhotoToobs beds. Photo: Toomey & Co. Auctioneers / The Chick ‘n’ Egg chair. Photo: Manuel Kretzer / Responsive Design Studio

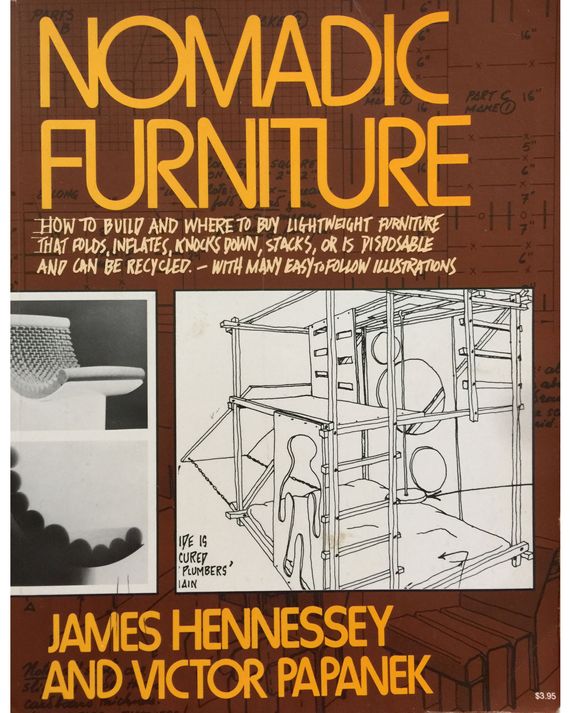

Most cardboard carpenters of the time preferred a DIY approach, offering instruction manuals and suggesting that lightweight furniture was part of a low-clutter lifestyle. Nomadic furniture, by James Hennessey and Victor Papanek, was produced on unbleached pages with handwritten text and diagrams, a brown and orange cover that screams 1973, and this caption: “How to Build and Where to Buy Lightweight Furniture That Folds, inflate, tip over, stack or is disposable and can be recycled. The authors also suggested that the flexibility of cardboard would help make affordable furniture to accommodate a wider range of ages, sizes, and abilities than average – which, again, makes sense. for an event that welcomes gymnasts and basketball players, Paralympians and Olympians.

Like his contemporary The Whole Earth catalog, Nomadic furniture has positioned this type of vernacular design as a universal resource rather than an expensive consumer product. His most shocking entry concerns a disposable child car seat (really a booster), created by Eddie Coleman and simplified by Hennessey into ten pieces that could be taken apart into a flat stack but also create a seat that curves around the body. Online forums that found this design are ruthless in their mockery, but given what is known about the strength of multi-layered board, especially when the layers are nested, this is an idea that at least deserves testing.

the Helmet of abuse prototype of 2012 is based on the same principle of the honeycomb: a thin cardboard alone can be fragile, but when crossed, it is rigid while remaining light. The Chick ‘n’ Egg chair by Manuel Kretzer uses his honeycombs to curve backwards rather than towards the skull, but could also be enlarged or reduced or, one imagines, horizontally, to provide a contoured surface large enough to elongate.

Nomadic furniture also has Toobs, designed by Jim and Penny Hull under the HUDDLE brand, which reused the cardboard tubes often used as molds for concrete columns as the basic structure of the pod-shaped beds and bunks. “The Hulls also see their design as a play environment,” the New York Times wrote in 1972, when the decor was shown at the Design Research store on East 57th Street in Manhattan. “While some [children] crawled in and out of the two-story tubes, calling them caves and houses, others scaled the unit to the top, riding the upper cylinders as if they were the king of the mountain. These, too, appear to be a more sleep-friendly environment with additional potential for the Olympians.

More prosaically, and just as inexpensive, cardboard was used for the dormitory furniture, which is all Athletes Village really is. In 2011, with a freshly printed architecture degree from the University of Waterloo, Geoff Christou and his friend Chris Porteous launched Our Paper Life, a reusable flatbed desk and shelf designed for students and sold for $ 19.99. “Instead of the paperless future, there is the paper office”, wrote the Toronto Star. In 2015, the founders returned with Room in a box, a full line of furniture in primary colors and more, with an introductory price of $ 249, which they tried (unsuccessfully) to fund through Indiegogo with the promise of a “30 minute movement”. While these products were less round than Gehry or the Toobs, the colors and combination of storage and sleeping surface also seem to be an improvement for athletes, who surely have plenty of sneakers to store in the niches under the bed.

Of Nomadic furniture by Victor Papanek and James Hennessey, published by Pantheon Books / Random House. From left to right : Photo: Alexandra LangePhoto: Alexandra Lange

Of Nomadic furniture by Victor Papanek and James Hennessey, published by Pantheon Books / Random House. From above: Photo: Alexandra LangePhoto: Alexandre …

Of Nomadic furniture by Victor Papanek and James Hennessey, published by Pantheon Books / Random House. From above: Photo: Alexandra LangePhoto: Alexandra Lange

So why don’t we live in a corrugated future? Blauvelt believes the cardboard revolution was ultimately doomed by IKEA, which created inexpensive furniture that seemed to last longer, despite being heavier and harder to put together. Plastics, which also took hold in the 1960s, are also portable and inexpensive furniture and storage, although they are less customizable and less recyclable. Most of us don’t actually want to do it ourselves, and it’s even easier now than then to receive furniture that is already assembled (in boxes). Cardboard comes back every now and then to fill a void in the consumer market, as with pieces from Adaptive Design Associates, or when needed, as with architect Shigeru Ban Paper log houses, built after the 1995 Kobe earthquake and subsequently adapted for disaster relief elsewhere. Gehry’s Easy Edges are now museum pieces, and friends of mine report moving the Our Paper Life pieces from place to place before they met their inevitable disappearance from the blue bin.

Cardboard was once the material for utopian dreams. But, as with the Games themselves, mired in cost overruns, political controversy and pandemic contagion, the fervor that changes the world is gone. Yes, it is laudable that the beds “are recycled into paper products after the Games, with the mattress components recycled into new plastic products,” as the organizers of the Athletes’ Village said. It would be even better if they were well enough prepared to continue their journey as beds, with no additional energy required, in shelters or student accommodation, or stored for the next natural disaster. In this way, cardboard would continue its decades-long struggle against the disposable.