The Upper East Side Rises Again, Thanks to Its Condo Boom

Some 50 condo buildings have gone up on the Upper East Side since 2012. The towers tend to be limestone, amenity-laden, and very popular with buyers.

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Courtesy of Naftali Group, DBOX, Michael Kleinberg, Elad Group, 40 East End

Melody Serafino moved downtown just weeks after graduating from college in 2005, and that’s where she thought she’d always be. “I was just such a downtown person for so long,” she says. The Upper East Side, if she thought about it at all, “felt like it was for frat boys and rich old ladies.” But then the 42-year-old and her husband spent the pandemic holed up in a 500-square-foot West Village apartment, only to reemerge to TikTok crowds swarming neighborhood standbys like Bus Stop (going out for dinner anywhere suddenly involved two-hour lines). So they started looking on the Upper East Side. “I love a prewar building, and we just wanted more space,” she says. In 2022, they ended up buying a three-bedroom co-op off Second Avenue — a move she’s even more pleased about as time passes. “I had this perception that we were going to come up here and it was going to be a restaurant desert and everyone was going to have 2.5 kids and a dog — we don’t have kids or a dog. But it hasn’t been like that at all. A lot of my favorite restaurants moved up here.” Many of her friends have too. And so, it seems, has everyone else.

Cafe Commerce is one of the many Downtown establishments that have moved to the Upper East Side recently.

Photo: Courtesy Cafe Commerce

In the last few years, what was once a sleepy, unglamorous section of the Upper East Side — specifically the area east of Lexington Avenue — has become, somewhat improbably, a destination. The food world has already taken note of newcomers like Chez Fifi and Veau d’Or (the latter reopened under Frenchette chefs), crediting them with reinvigorating the moribund French scene. The side streets are packed with little cafés and buzzy restaurants — Sushi Noz, Heidi’s, Hutch & Waldo, Hoexters — and West Village hot spots Cafe Commerce and American Bar have both moved to Lexington. Casa Tua, the private club and restaurant at the revamped Surrey Hotel, is packed nightly with “the rich kids of Instagram,” says a broker who was born and raised on the Upper East Side. She added, “I wouldn’t have been caught dead in a place like that in my 20s.” Or at Bemelmans, the bar at the Carlyle where crowds of 20-somethings now line up outside. “It’s the stuffiest bar,” the broker says. “I used to go there with my grandmother.”

For years, the blocks east of Lexington were a hodgepodge of brick tenements, workaday postwar buildings, parking garages, hospitals, nail salons, delis, and uninspired glass towers, the humdrum counterpart to the grand, stodgy co-ops on Fifth and Park, whose old money (and often literally old) residents patronized Madison Avenue’s high-end boutiques and middling, overpriced French and Italian restaurants. When Madonna bought a townhouse on East 81st between Second and Third in 2009, the New York Times referred to the area as “the back of beyond” and brokers scoffed at her foolishness for spending upwards of $30 million to live “in the sticks.” But since 2012, 47 new condo towers have been built on the Upper East Side — the majority of them east of Lexington — with five more currently under construction, according to real-estate data firm UrbanDigs. This is shifting the center of the neighborhood eastward. “I’ve been doing this for the past 32 years,” says one prominent townhouse broker. “And all the fancy stuff is moving east. I tell you, the Upper East Side is swinging again.”

Buyers have shown themselves willing to move to the fringes of established residential neighborhoods for amenitized condos like 255 E. 77th. In this context, Yorkville, a 10-minute walk to Central Park with tree-lined streets and good schools, is hardly a stretch.

Photo: Naftali Group

To some, or possibly a large, extent, the Upper East Side’s glow up can be attributed to the new buildings themselves — they are, almost to a one, done in the neoclassical style of Robert A.M. Stern (and many of them are, in fact, designed by his firm), or other traditionalist stalwarts, like William Sofield and Peter Pennoyer. The look is decidedly prewar: limestone-clad with elegant ornamentation, bronze accents, arched windows, terraced setbacks, and every modern comfort and amenity — like a sunlit swimming pool on the 17th floor.

Unlike the gaudy supertalls on Billionaires’ Row, the vibe is quiet luxury — the average price for a condo is $4.98 million, according to UrbanDigs, a notch higher than the Manhattan new-development average of $4.28 million — and they’ve sold extraordinarily well. (Multiple brokers used the word “hotcakes.”) The ongoing demand and the prices in excess of $2,000 per square foot, with some going for as much as $4,000 per square foot, seem to surprise even some of the people selling them. When the Beckford, a limestone tower at 80th and Second, went up next to an Enterprise Rent-a-Car in 2019, the block was “a nightmare,” according to one broker. Now, not one of the 72 units is currently listed, and a two-bedroom recently sold for $4.87 million — nearly a million more than it traded for four years earlier. “I still get calls about a listing I had at the Beckford,” says Claire Groome, an associate broker at Sotheby’s International Realty. Meanwhile, she’s having trouble selling a loft that needs work downtown, the kind of thing buyers would have been all over 15 years ago.

The Benson, one of the condos developed by Naftali, arguably the dominant developer of this type of Upper East Side product.

It’s not at all surprising that buyers would go for these buildings — they have increasingly favored condos over co-ops for decades now. In addition to all the amenities, there’s the ability to buy and sell without board approval, to sublet, to use the apartment as a pied-à-terre, and to keep one’s finances and identity concealed. (When you buy from the developer, “it’s like buying a computer,” one broker told me. You sign the contract and that’s it.) For the most part, living in new construction condos meant moving to the fringes of established neighborhoods, spending tens of millions for glass boxes on the Westside Highway and the luxury lofts next to Dumbo’s clattering elevated trains. In this context, Yorkville, an entirely pleasant neighborhood a ten-minute walk from Central Park, with leafy streets and good schools, isn’t such a stretch. The Second Avenue subway, which opened in 2017, helps too.

In the first few years of the Upper East Side development boom, many of the buyers were longtime locals — people downsizing from palatial co-ops by Central Park to slightly less palatial condos a little further east, giving up a few thousand square feet for swimming pools and gyms and terraces they could drink cocktails on in the evening. There were young families, too, often ones who’d grown up in the neighborhood and whose parents were paying, says Alexa Lambert, a Compass agent who has sold out a number of Naftali projects. (Naftali, arguably the dominant developer of this type of product on the Upper East Side, is famous for never negotiating on asking prices.) These returning Upper East Siders “don’t want to relive their childhoods and move into a big stuffy co-op on Park Avenue. They want something cooler: an open kitchen, better ceiling height, an amazing gym,” says Lambert. James Morgan, also of Compass, describes the mood as “Polo Club — younger, wealthy, but relaxed. People who appreciate design and are more tuned into trends.” Morgan recently sold a $25 million penthouse at the Armani Residences to a local buyer. Like many of the neighborhood’s condo buyers, she could have easily qualified for a co-op, he says, “but she shunned that vibe.”

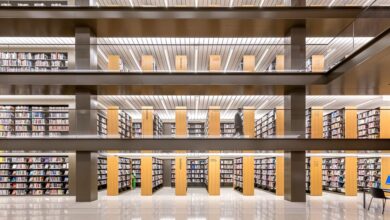

A music room at the Harper. Like all of the new developments, it offers a full array of amenities.

Photo: M18 Public Relations

The biggest shift, however, came during COVID, brokers and developers say. The resistance to moving (or moving back) to the Upper East Side vanished. “Even through 2018, most of my clients wanted to be downtown in these loft buildings, where it’s hip and cool. But during COVID, it changed. People want more amenities, they want access to green space, they want to be close to their kids’ schools,” says Peter Zaitzeff, a Serhant agent. “People also want to live in staffed buildings; they want the security, the garages, the porte-cochères.” Some of those desires may have been based on unsubstantiated fears — pied-à-terre shoppers convinced that Soho was crime-ridden — but it produced a real shift. There was, too, the fact that so many of the city’s wealthy residents had weathered the pandemic’s early months at roomy second homes outside the city. They came back to crowded downtown restaurants and apartments and longed for something more spacious and bucolic.

“Post-COVID, buyers were less interested in up-and-coming neighborhoods,” says Alex Olsen, chief operating officer of El Ad, which is developing the 74, a 32-story white terracotta tower designed by Pelli Clarke & Partners on 74th and Third. “People want more stability in their address, and nothing is more stable than the Upper East Side.” Dana Haddad, an educational consultant who advises families on school placement, agrees. Before, she says, families were often drawn to the neighborhood’s private schools — 22 as opposed to all of downtown’s 14, including all but one of the city’s single-sex schools — but were reluctant to actually live there. “They don’t mind coming anymore,” she says.

It’s also a (relative) bargain compared with downtown. Doron Zwickel, a Core agent who’s selling the Harper on 86th and Second — a blocky, modern ODA-designed building that’s still, in the fashion of the neighborhood, clad in limestone — says that among the buyers were a downtown couple who were pleased to be able to buy larger, higher-floor apartment than they could have in their old neighborhood. Edward Hertzman, a 40-year-old media-company founder, was living downtown when he bought a two-bedroom apartment on 77th and Second in 2019 because he thought it was the best real-estate investment he could make at the time. “My broker was very honest: ‘You could get a bachelor-pad, lofty thing downtown or a lot more for your money uptown,’” he recalled. He paid $1.2 million and did a major renovation. “It’s amazing how many people I’ve dated who’ve said, ‘Oh, I don’t want to live up there,’” he says. “But nightly, I’m at Lusardi’s, Hoexters, the Mark, the Carlyle, Elio’s, Melody’s, and I just applied to Casa Tua.” Increasingly, his downtown friends, who used to insist he meet up in their neighborhood, have started coming up of their own accord, suggesting they hang out after a sound bath at Sage & Sound (co-founded by echt Upper East Sider Lacey Tisch).

Developers seem eager to cater to this new demographic. At 255 East 77th, the design is by RAMSA, with the kind of classic exterior you’d expect, but the interiors are loftlike, with soaring ceilings and open layouts, and the amenities spaces are by “It” design studio Yabu Pushelberg. The Archive Lofts, a coverted MoMA storage facility on East 61st, bills itself as “Tribeca-style living with an East Side address.” (Aire Ancient Baths, first established downtown, is also opening downstairs.) These are buildings that draw from the neighborhood’s architectural history, especially its prewar styling, but strive for a more downtown sensibility.

Not everyone loves the neighborhood’s glitzy new persona. For decades, Yorkville has been a neighborhood of middle- and upper-middle-class professionals — the kind of people who might rent a $2,000 studio in their 20s and upgrade to a $1 million two-bedroom in their 30s. It was unglamorous but homey, a place of walk-up buildings, mom-and-pop shops, and affordable-ish apartments. “It used to feel like Yorkville was one of the last vestiges of old-ish New York,” says a 44-year-old mom of three who’s lived in the neighborhood for 17 years. “It was one of the most neighborhood-y neighborhoods.” Its uncoolness protected it from the hypergentrification that consumed places like the Village, but now “it’s pretty much all luxury condos going up that are unaffordable to anyone who doesn’t make $600,000 a year and hardly any retail,” says the mom. On the two blocks of York Avenue near her apartment, there’s a dry cleaner, a deli, a nail salon, a small grocery, a doggy daycare, two bars, two restaurants (a poke place and a sushi place), a bodega, and an art-framing shop. If a limestone tower goes up, she’s afraid they’ll all be wiped out, replaced by an Equinox and a Pecora Bianca. It’s not like she and her husband are hard up — they live in a four-bedroom co-op they created by combining two units — but they’re not Casa Tua people, either.

“Usually these buildings replace old tenement buildings that were multiuse. They’d have a number of relatively affordable apartments and three or four shops,” says Zeynep Turan, manager of preservation at Friends of the Upper East Side. A lot of the new condos, despite being much taller than the low-rises they replace, don’t even add housing units, she points out. The concern, for existing residents, is what might follow in the wake of desirability — everyone wants to move to a cool neighborhood, but it can be unnerving to watch your own neighborhood become one. Especially since some of the East Side’s rise has been fueled by people and businesses fleeing neighborhoods like Tribeca and the West Village, whose charm has been diminished by extreme wealth and an impossible dining scene. “It’s always about rent,” says Cafe Commerce chef Harold Moore, who owned a series of West Village restaurants before deciding it was time to come back to the Upper East Side, which was hot when he started his career in the ’90s and now, it seems, is again. “The pendulum always swings back. I can come up here and not have to serve chicken wings to make the rent,” he says. In fact, it reminds him of the West Village when he first opened there — with its art galleries and bookshops and weird little spots coexisting with the corporate stuff. Plus there are still lots of longtime residents, not just people passing through. He did, he admits, get a lot of “Are you sure?”s from friends and people in the industry when he told them he was going to the Upper East Side.

They needn’t have been concerned. A month and a half after opening, it’s hard to get a dinner reservation at Cafe Commerce — as of Tuesday, the only reservations available for this coming weekend are 10 p.m. or later. And the TikTokers have already started descending on neighborhood institutions like Butterfield Market and Zitomer. Now locals are starting to worry that soon they might not be able to get a table at their old standbys. Lambert, the Compass agent, was telling me about her favorite Upper East Side hotel bar, an old establishment kind of place (that’s not Bemelmans), where she now regularly sees tables of 30-something cool kids. “What is it?” I asked. She hesitated. “Don’t put this in your article — I don’t want everyone to start going there.”