The Design Story Behind Taschen’s SUMO Book Stands

Photo illustration: Courtesy of Taschen

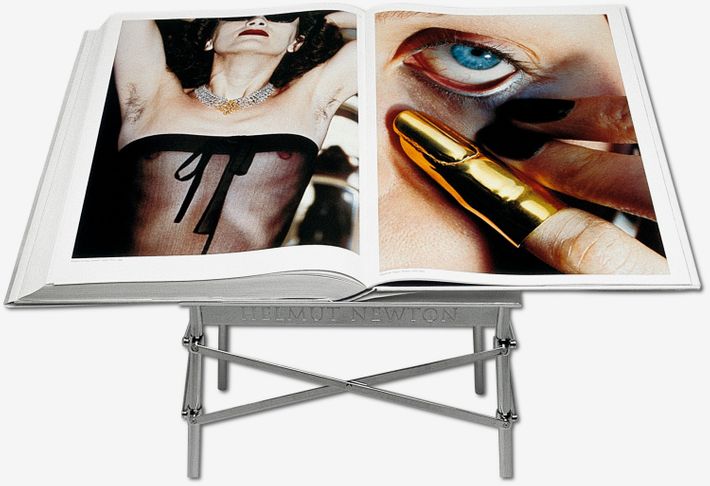

In 1999, Frank Goerhardt, a book printing engineer at a small art press in Verona, Italy, received a call from Benedikt Taschen. The German publisher, known for its experimental art books, wanted to create a 2-foot-tall volume and 50 books of Helmut Newton photographs – a scale that would make reading feel like attending an exhibition in a private gallery. And he wanted to print 10,000 of them. “There was no machine on the market that could do that!” Goerhardt remembers. Such a large art book should be sewn by hand. If Goerhardt’s press was running at full capacity—it could bind a maximum of 40 books a week—it would have taken almost five years to complete the order. So he asked the other European presses and kept hearing that it was impossible. On the verge of giving up, he found a bookbinder in northern Italy who would build a custom machine if Taschen paid up front. With this, the publisher’s SUMO series of extremely large and very heavy books – which may even surpass the Newton edition – began.

Philippe Starck designed the stand for a 1999 SUMO edition of Helmut Newton’s photographs.

Photo: Courtesy of Taschen

Photo: Courtesy of Taschen

Taschen presents books as fetish objects — objects to be revered and coveted. And a group of voracious collectors are eager to oblige, ready to deposit $25,000 on this Helmut Newton book (if a copy ever goes on sale) or $40,000 for a collection of Ai Weiwei Papercuts encased in a bright red shell. Goerhardt, who is now Taschen’s head of production, a position he held for nearly 20 years, knows the industry so well he can tell a book’s provenance just by the smell. ink on the page. This refined sensitivity helps him to understand how to make a A $6,000 book looks like a Ferrari engineto print Neil Leifer’s boxing photographs on ready-to-install aluminum panels, and reproduce transport cases that Renzo Piano uses for his architectural models. “We’re extremely open-minded to trying new things,” says Goerhardt.

Perhaps even more than books, the best examples of Taschen’s obsessive approach are its personalized media, which are meticulously crafted for each edition they accompany. However, these are not derived from the company’s maximalist tendencies. “The original idea came from Benedikt, who was absolutely right,” says Goerhardt. “You have to add a desk or stand with the book because no one knows where to put them.”

Renzo Piano used tensile forces – a feature of his architecture – in the design of a stand for Sebastião Salgado’s book Amazon.

Photo: Courtesy of Taschen

The stands are essentially miniature works of architecture created by designers and architects like Philippe Starck, Shigeru Ban and Marc Newson. The first, for the Newton book, was designed by Starck, who was the architect of the Taschen stores at the time. He created a metal stand with four legs supported by braces that folded flat and could be shipped with the book. Collectors criticized the way it tipped over when the weight of the book shifted from the right side to the left as they read it, but Taschen praised its lightness, an attribute that informed subsequent lecterns.

More recently, Renzo Piano designed the stand for a new SUMO book about the photographer Images of the Amazon by Sebastião Salgado. “When we met Renzo, he said, ‘When you have this book open, it must fly like an albatross, this heavy bird in the middle of nothing,'” Goerhardt explains. Piano wanted the structure to be as subtle as possible, and Goerhardt wanted to make sure it could survive a trip to Singapore or Australia in pristine condition. The architect designed one that was supported by tensile forces, a structural construction technique that Piano has used throughout his careerparticularly in his conception of the Center Pompidou and the Columbus Exhibition in Genoa. Taschen, Piano and the manufacturer developed a dozen prototypes and tested their resistance to shipping. They found that the vibration loosened the structure, so they tweaked the design – using larger steel rods, adding adjustable screws to level the bracket, and squeezing some stabilizer liquid into it – to prevent it to open during transport.

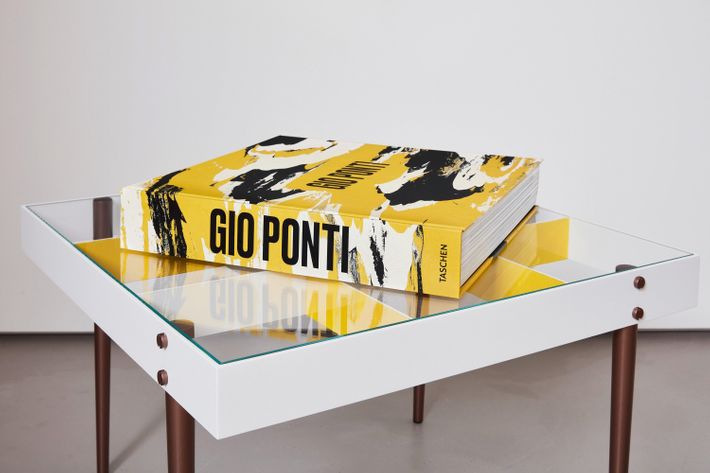

Taschen worked with the Gio Ponti Archive and furniture maker Molteni&C to revive an archival design by the Italian architect to accompany a monograph of his work.

Photo: Courtesy of Taschen

In rare cases, rather than commissioning an original design, the subject provided the concept themselves. For a book Gio Ponti SUMO, published in 2021, Taschen worked with Ponti’s grandson, Salvatore Licitra, who also designed stores for the editor. Licitra, which manages the Bridges Archivesfound the designer’s drawings for a square version of the Harlequin tables which he had created for a private commission. Only two prototypes were produced, and Taschen commissioned Molteni&C, an Italian high-end furniture manufacturer, to create the SUMO editions. “We thought it was a beautiful artistic vision to achieve – and we wanted the real thing,” Goerhardt says.

The case and support designed by Marc Newson for a book on Ferrari are inspired by the engines of the Italian car manufacturer. Courtesy bags.

The case and support designed by Marc Newson for a book on Ferrari are inspired by the engines of the Italian car manufacturer. Courtesy bags.

The most complicated stand to date came with a collector’s edition book about Ferrari. With its red housing, industrial bolts and aluminum pipes, it mimics the appearance of a Ferrari engine and ended up being almost as complicated as making one. news about — the industrial designer behind the Apple Watch, Leica’s red cameraand the Lockheed lounge chair, the most expensive design object ever sold — designed both the book and the stand. For the aluminum case, Taschen worked with a Spanish automotive manufacturer, another supplier provided the decorative rubber buttons that you lift to open the case, and another team color matched and painted the case in the exact shade of red that Ferrari uses on its engines. An Italian producer who makes exhaust pipes for motorcycles contributed to the stand’s polished pipe-like legs. Taschen also convinced the maker of horse emblems mounted on Ferrari hoods to produce a special one for the cover of the book, which is made from the same leather used to cover car seats. The project lasted two years.

A tripod design by Newson has been modified for several SUMO books. Courtesy of bags.

A tripod design by Newson has been modified for several SUMO books. Courtesy of bags.

However, not all desks involve a dozen vendors or extreme testing. For multiple projects, Taschen has adapted its simplest medium: a Newson acrylic tripod that accompanies SUMO Edition books on the works of Annie Leibowitz, David Baileyand David Hockney. The design is changed slightly for each title – black legs for Leibowitz so it looks more like a photographer’s tripod, primary colors for Hockney that reference his vibrant palette – but in concept it remains the same. “It is the most convincing table from a practical and technical point of view,” says Goerhardt.

Lecterns may have been born out of this pragmatic need, but over the past 20 years they have become works of art in their own right.